Eight years ago, the Central Freeway fell, and the sky didn't. The neighborhood long obscured by the structure came up for a year-long breath of air during its reconstruction.

Author Carol Lloyd described the transformation in a 2003 San Francisco Chronicle article:

The buildings are familiar, but they look brighter, prettier, somehow. There are big swooshes of empty land, open views down Valencia all the way to Market Street, and a lovely glimpse of the new Victorian/postmodern Gay Lesbian Bisexual Transgender Community Center, perched on the corner of Market and Waller streets. Sunlight is falling on asphalt that has been steeping in urine and shadows for decades. The air doesn't smell anymore, nor does it vibrate with trucks rattling overhead.

"It was awesome," said resident Alison Miller. "There was sunlight, and people started to really know their neighbors. You'd look at Valencia Street and think, how could they think of covering up this potentially vibrant neighborhood in the middle of the city?"

For fifty years, the motor-dominated streets around the Central Freeway have felt dangerous and forbidding to walk on, leaving a rift in the Market-Valencia commercial corridor. Even naming the ambiguous cross-section of districts has been a challenge for San Franciscans, who have called it "North Mission," "SoMa West," "The Valencia Bottoms," and even "Deco Ghetto," though nothing has really stuck.

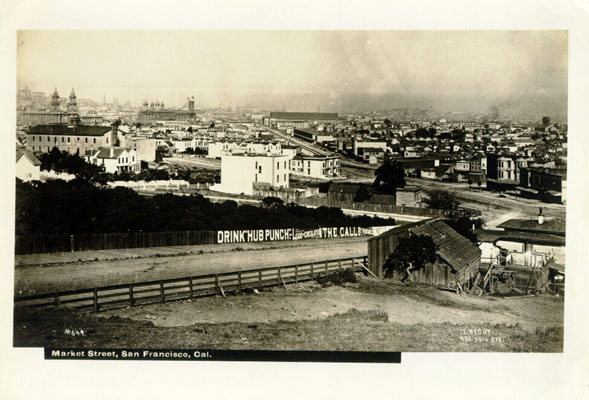

This year, the neighborhood is finally getting some long-awaited streetscape improvements, including a civic space unofficially dubbed the McCoppin Hub. The name goes back a hundred years to a time when "The Hub" was a major streetcar junction at the intersection of Market and Valencia Streets. It came complete with a cable car powerhouse and railcar repair shops, and even had a drink named in its honor: "Hub Punch".

McCoppin Street was named after Frank H. McCoppin, San Francisco's ninth mayor (1867 - 1869) and superintendent of the Market Street Railway.

The powerhouse was removed after the 1906 earthquake, and the double-decker Central Freeway was built one block away in 1959. In its location today are a Travelodge motel, Flax art store and a car parking lot.

After the freeway was damaged in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, the upper deck west of Mission Street was deemed unsafe for use. San Franciscans voted twice to remove the stretch before approving a plan in 1999 to rebuild today’s ramp that ends at Market Street.

Alison Miller protested the freeway's return along with Lynn Valente with a few other residents under the banner of McCoppin Street Neighbors (the North Mission Neighborhood Alliance has since become more prominent). But Valente said she found it wasn't easy rallying together a "transitional" community where neighbors have few inviting places to get to know one another.

"It's no man's land," said Valente. "[The freeway] is our line. The merchants on the other side aren't gonna get involved."

“We had this whole ‘Halt the Ramp’ campaign," said Miller. "We fought really hard to stop them from rebuilding the only freeway to be rebuilt in San Francisco."

North of Market Street, the freeway was ultimately replaced with the Octavia Boulevard project, leading to a revitalization of the Hayes Valley neighborhood.

But despite the protests of residents and some supervisors, the city rebuilt it south of Market, under pressure from Caltrans, which manages the state's freeways, and the result of a ballot measure sponsored by a coalition of driving residents, mainly in the Sunset and Richmond districts.

Building the Central Freeway was "a transportation planning decision that resulted in five decades of negative urban design impacts and blight on the surrounding neighborhood," said a SF County Transportation Authority (SFCTA) study of alternative design proposals to remove the freeway.

Today, the freeway sits over the neighborhood twice as wide, rather than twice as high. Its reconstruction, when compared to a boulevard alternative, saves two minutes for drivers, at the most, according to the SFCTA study.

"Nobody wanted to see the freeway end at Market Street. Nobody wanted to see the freeway go back up over Valencia or Mission Street," said Livable City Director Tom Radulovich, who served on the Central Freeway Citizens Advisory Task Force.

"The reality back then was, from the task force at least, the Hayes Valley representatives who lived north of Market really wanted to see the freeway removed further south of Market," he said. "The Mayor's Office really just didn't have enough courage at the time to push back against Caltrans."

Removing the freeway farther back, he noted, may have even garnered less car congestion than the current layout. "The SoMa street network has a lot more capacity than the north of Market Street network, so there's a bigger opportunity to deal with the freeway traffic," he said.

The campaign south of Market also lacked political support from then-Supervisor Chris Daly, who recused himself from voting on the issue due to a conflict of interest: he owned a condo at the corner of Valencia and McCoppin Streets, and removing the freeway would have likely increased his property value.

"It was too political, and Caltrans, they wanted a job," said Miller. "We got shafted."

Today, the streets around the Central Freeway remain neglected, and neighbors say they have long attracted unwanted activities like drug use, dealing and other crime. Those conditions used to extend all the way into Hayes Valley, said Miller, where "nobody would deliver pizza to your house" before that stretch of freeway was removed.

"Now look at it," she said. "It's improved their neighborhood, but ours, I would say, is the same."

Some McCoppin neighbors may resent - or at least envy - the success Hayes Valley has enjoyed. In Lloyd's 2003 article, resident Leslie Kossoff said those south of Market Street "got screwed."

"They're Oz, and we're Kansas," said Kossoff.

"One only need to look at Valencia Street and then cross Market to plainly see the difference," said Miller. "On one side of Market is a beautiful tree-lined boulevard with a green park, community gardens and a farm, while here we have a dark overpass, filthy sidewalks and nothing but concrete."

Valente, on the other hand, is pleased by the coming improvements to the neighborhood. The McCoppin Hub, when it sprouts up next year, could finally give neighbors a place to meet one another and help mend the fabric of the community.

"We're not bitter," she said. "I'm proud that a small group of us have been successful in getting funding for amenities that will mitigate the effects of the project."

"I hope that we can keep our eye on the big picture," said Valente, "and that outside influences might give those of us who live and work here a chance to realize the neighborhood that we have planned and waited for for more than ten years."