After years of delay, the 2016 target date for the Van Ness Bus Rapid Transit project seems more tangible than ever. The San Francisco County Transportation Authority recently released its draft environmental impact report and will select one of several proposed design alternatives in the spring.

The SFCTA is asking for public input on the different options and the draft report, which includes a trove of information for planners and transit advocates to consider when weighing each design.

Last week, the San Francisco Transit Riders Union's Rapid Transit Working Group met to discuss the alternatives.

“Ultimately, we’re looking at what is going to create the best, 21st-century riding experience for transit riders on Van Ness Avenue,” said SFTRU board member Rob Boden. SFTRU members are considering which design to endorse, but the organization hasn’t taken a stance yet.

The group’s top priorities, said Boden, are improving transit reliability and passenger comfort. The EIR analyzes those factors along with everything from median widths and greenery to bus weaving.

Bus Rapid Transit has appeared in a variety of forms in cities around the world, but generally includes amenities like dedicated lanes, pre-paid ticketing, all-door level boarding, and limited stops that feel more akin to riding a rail system than a bus.

For the Van Ness project, the most significant question boils down to this: Should buses run between a pair of medians or alongside a single center median?

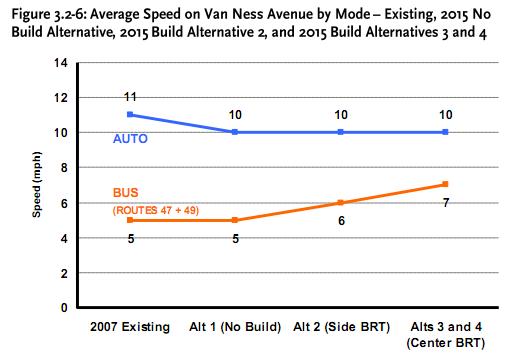

The EIR analyzed three design alternatives (plus a status quo scenario), but only the two options that place bus lanes in the center of the road appear to maximize the project goals of improving bus speeds, reducing operating costs, and increasing ridership. Each of those options carries some pros and cons.

On one hand is the dual median alternative, which would separate a two-lane busway from other traffic by placing it between two medians, where passengers would disembark from the right side of the bus. One problem with this design, the report says, is a risk of delays and head-on crashes when one bus needs to pass one another. The price tag for construction ($130 million, compared with $119 million for the other center-running alternative) and maintenance of the busway and landscaped medians is also higher than the others, and it would require the highest number of median trees removed.

The other center-running alternative would place each bus lane on either side of a single center median. Since boarding at BRT stops would be limited to the left side, buses would require doors on both sides to use the platforms (buses would still need right-side doors for the remainder of their routes). This could limit Muni’s flexibility with its vehicle fleet, and buses operated by Golden Gate Transit would only be compatible with one stop on the two-mile stretch (between Geary and O’Farrell).

Tilly Chang, the SFCTA's deputy director for planning, said staff has consulted other municipalities that have used BRT vehicles with doors on both sides, including in Cleveland, Ohio and Eugene, Oregon.

"We found that they have not experienced significant incremental operations and maintenance costs versus their right-door only buses," said Chang. "However, this requires further study before assuming a similar experience would be the case here, and we are undergoing that exercise right now in as much as it can inform the decision-making process."

Another concern raised by SFTRU members about the design is the lack of a physical barrier preventing other vehicles from entering the bus lanes, but Chang said the lanes could be slightly raised.

On the upside for the alternative are wide refuge medians for pedestrians, added separation between the boarding platform and auto traffic, and the quickest and least intrusive construction period of any of the alternatives.

For both center-running alternatives, it’s also worth noting that planners have the option to prohibit all left turns on the corridor (save one in each direction at Broadway and Lombard). This measure, called "Option B", would maximize the project’s benefits in virtually every criteria, including lowering operating costs from $6.1 million to $5.6 million and reducing vehicle crashes, according to the report.

The third design alternative, which would place bus lanes on alongside parking lanes, would yield the poorest results for transit performance, according to the report. Bus speeds are projected to increase only about half as much as the center-running designs, and this configuration would carry the highest operating costs.

That’s no surprise, given the lanes would likely see frequent incursion by other vehicles. The problem can already be seen on existing bus lanes on Mission, Geary, and O’Farrell Streets, where drivers frequently stop in them to make right turns, pull into parking spaces, and double park. As a result, passengers are subject to constant delays as buses weave around other vehicles.

Colored pavement treatments, included in each of the design alternatives, could mitigate that effect by discouraging drivers from entering the lanes, but it’s no substitute for center-running, separated bus lanes.

The SFCTA's next presentation on the project will be an online webinar on Monday, December 5th at noon.

To find other meetings, learn more, and submit comment, see the SFCTA website. You can also get complete details on the design alternatives in the EIR's Alternatives Analysis chapter [PDF].