Once bus rapid transit is finally up and running, Geary Boulevard will carry thousands fewer cars every day in 2020, compared to a scenario where it doesn't get built.

That's according to a preliminary analysis [PDF] presented by the SF County Transportation Authority. The traffic counts vary, depending on which of several design alternatives are built, and some of the cars taken off Geary during rush hours would divert to parallel streets instead. Nonetheless, a Geary without bus rapid transit would have more cars than one with it.

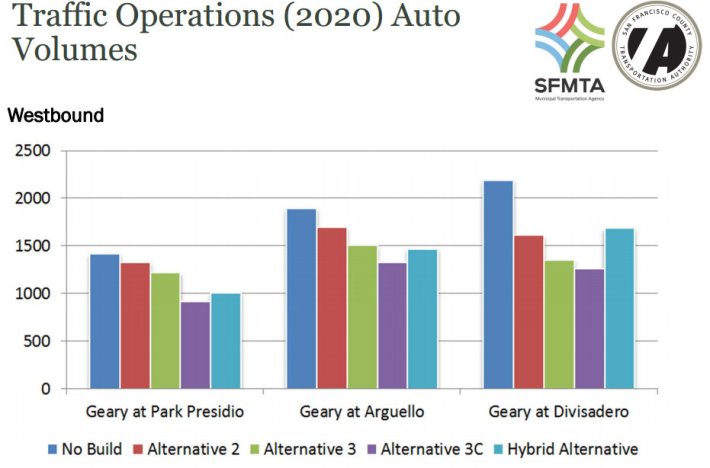

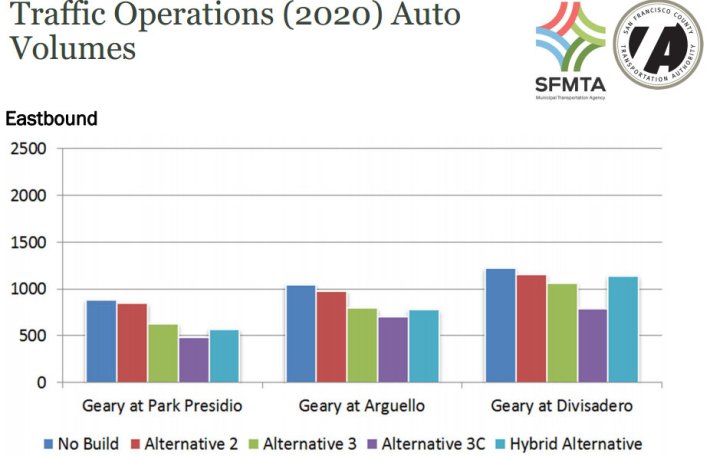

Just how big is the difference? A traffic projection for the intersection of Geary and Divisadero Street shows about 2,200 westbound cars each hour -- compared to about 1,000 fewer cars with the Geary BRT "3-Consolidated" option. However, the SFCTA doesn't plan to build that option, as it would require the expensive undertaking of filling in the Fillmore underpass.

The SFCTA's "preferred" option is the "hybrid" alternative, which only includes bus-only center lanes in the Richmond District. The other three quarters of the Geary corridor would get side-running bus lanes, many of which exist today.

Under the "hybrid" scenario, projected car traffic at Geary's intersections with Arguello and Park Presidio Boulevards within the Richmond are only a bit higher than in the 3-C scenario -- a few hundred more cars a day on Geary. At Geary and Divisadero, however, eastbound car volumes are almost as high as in the status quo, and westbound car volumes are somewhere in the middle.

As for the numbers of drivers expected to use parallel streets instead, the numbers range between 200 and 700 cars hourly during peak hours, depending on the intersection. The effect is most pronounced at Webster Street, just east of the Fillmore underpass, where Geary is only slated to get side-running bus lanes.

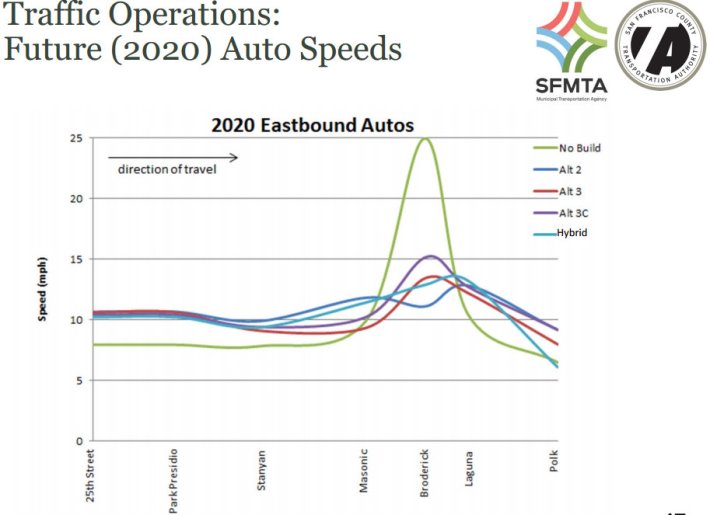

It's also worth noting that driving speeds on Geary are expected to remain mostly unchanged, with drivers seeing the slowest speeds under the status quo, and the fewest delays under the more aggressive 3-C scenario. Each BRT scenario would, however, slow down eastbound drivers within the speed-plagued stretch between the Masonic tunnel and Laguna Street.

The bigger implication of this study, of course, is that it reinforces the notion that, when streets are prioritized for higher-quality transit service, people will opt to use it. That effect has been seen in other cities. As Walter Hook, executive director of the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, said in a Streetfilm, BRT lines typically yield a 10-20 percent shift away from cars. When New York City implemented "Select Bus Service" improvements and a parking-protected bike lane on Second Avenue, car traffic on one segment dropped 11 to 23 percent.

Once San Francisco eventually, finally constructs BRT, we'll have our own local example to point to.