SPUR has set adrift its proposal to halve the size of the Great Highway along Ocean Beach, as the group strives to avoid distracting attention from implementing the other priorities in its Ocean Beach Master Plan. A road diet may be revisited later, once more pressing concerns have advanced.

SPUR calls the OBMP "a comprehensive vision to address sea level rise, protect infrastructure, restore coastal ecosystems and improve public access." It also includes proposals to remove other sections of the Great Highway that are threatened by severe erosion, in what's called "managed retreat."

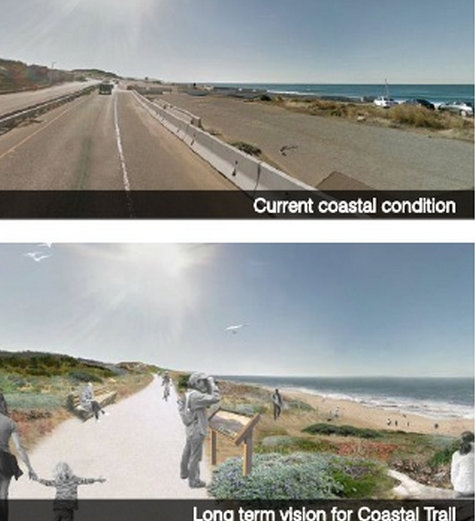

Ben Grant, SPUR's project manager for the OBMP, said one of the plan's most pressing priorities is closing a short, severely eroded section of the highway south of Sloat Boulevard, and replacing it with a walking and biking trail. Car traffic would be re-routed onto Sloat and Skyline Boulevards, which still would see less traffic than they're built for.

But the "most controversial" piece of the OBMP plan, said Grant, was the proposal to remove two of the four lanes on the main stretch of the Great Highway, as well as adding parking spaces along that stretch to replace those that would be removed south of Sloat. SPUR doesn't want opposition to those elements to distract from the more urgently needed road closure south of Sloat.

"We've gotten quite a few strong negative reactions to this," Grant said at a recent SPUR forum. "We're not going to be pushing for it at this time, because we have much more core, transformative projects to consider."

Nothing in the OBMP is an official city proposal yet, but SPUR's ideas are being seriously considered by public agencies that will conduct environmental impact reports for them.

"It's an interesting thing to think about," said Grant. "What if we take our one major stretch of oceanfront road and think of it not as a thoroughfare for moving through -- [but] think of it instead as a way of accessing and experiencing the coast, as a coastal access or park road?"

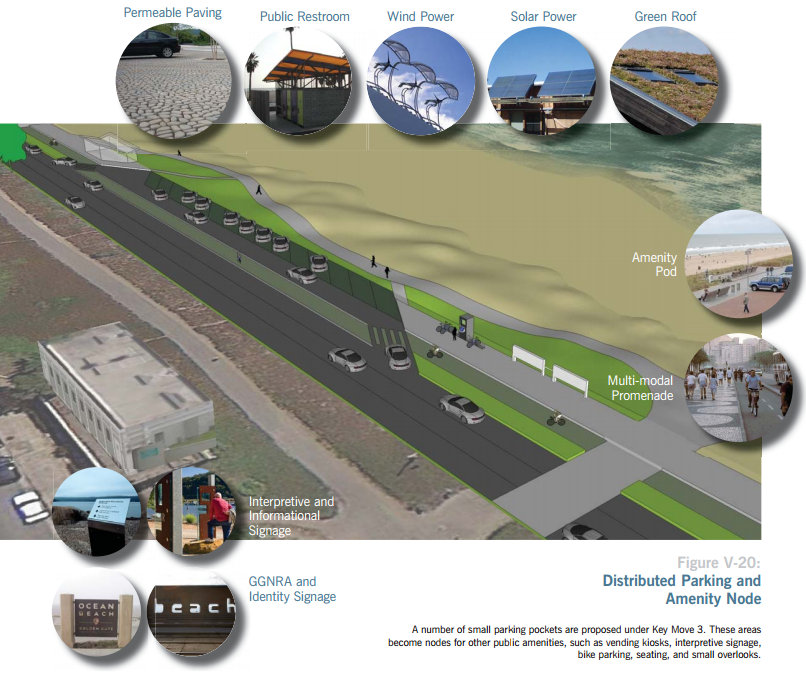

Removing the Great Highway's two western traffic lanes would provide room for "a wide shoulder for cycling and emergency access, dune restoration, and amenities," the OBMP states. It would also slow down car traffic compared to the current high-speed design, which encourages drivers to speed between red lights, and so make the highway safer to cross and to drive on.

"Sloat, Skyline, and Great Highway are effectively state-of-the-art highway design from 1938," said Jeff Tumlin, a principal transportation planner at Nelson/Nygaard, who helped craft the OBMP. "These are roads that were designed effectively for about 70 mph motor vehicle traffic. These are not urban streets."

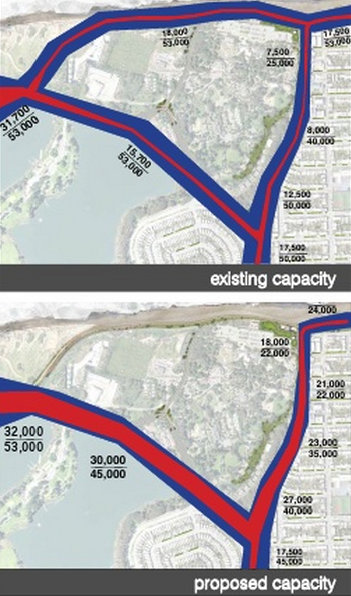

The OBMP traffic study found that the Great Highway typically carries about 18,000 cars a day, less than half its capacity of 40,000. That's less traffic than on Valencia Street, which was put on a road diet in 1999 and carries about 20,000. The traffic engineering rule of thumb, said Tumlin, is that each traffic lane has a capacity of about 10,000 cars per day, so a Great Highway with two lanes would still have room for 20,000 cars.

"Managing safety by managing speeds in this area, treating these more like urban streets rather than strange fragments of suburban freeways, can help achieve a better balance for all modes of transportation," said Tumlin.

The road diet would remove the two coast-side traffic lanes and create a buffer space for rebuilt dunes. That could reduce the roughly 60 times each year when the highway is closed due to sand blowing on to it. During sand closures and Sunday Streets events, drivers are detoured on to Lower Great Highway, a residential street.

The opposition to the road diet primarily comes from Lower Great Highway residents, who fear that removing lanes will divert more car traffic to their street at all times.

"When traffic does get diverted on to Lower Great Highway... it really is a safety issue, and an inconvenience for those of us in a residential neighborhood," said Tom Butler, a Lower Great Highway resident who voiced his opposition to Supervisor Katy Tang's office. "The experience belies what the study would suggest."

Butler acknowledged that cities that have implemented road diets "have become more friendly, liveable and nicer to be in," but still fears there will be more car traffic on his street.

The other main sticking point for the OBMP was the proposal to add small parking "pockets" along the Great Highway, in the middle of the Sunset District stretch between current parking lots near Sloat and Lincoln Way. Grant said the pockets would replace spaces to be removed along with the road south of Sloat, but that a new parking lot could also be provided there instead for drivers to access the beach and the new trail.

Neighbors say they fear that new parking along Ocean Beach would add to car congestion, and would require police patrols at a time when SFPD is already stretched thin.

"All of us who live on Lower Great Highway bought our houses knowing that that was a residential neighborhood, not a beach location," said Butler.

Brian Veit, another neighbor, said the city should also not build more "free" parking, which "is a misnomer."

"The city and the taxpayers should not foot the bill for a free subsidy to drivers that non-drivers do not get," he said.

Livable City Director Tom Radulovich said it's "disappointing" if the Great Highway road diet is dropped from the plan, but that if "if it's just phasing, that's fine."

"It'll be an uphill struggle, but there's lots we can do to enhance public access to the beach in the near term," he said.