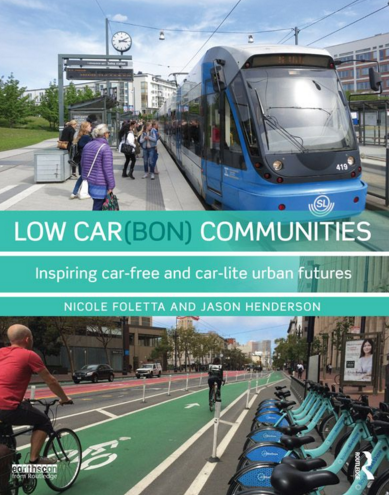

A wise man once said there are few if any urban planning problems that haven't been solved somewhere on earth--the challenge is just finding the best stuff to copy. That's the approach of Low Car(Bon) Communities: Inspiring Car-Free and Car-Lite Urban Futures, a new book by Nicole Foletta and Jason Henderson, published by Routledge. Foletta is Principal Planner with BART, with experience working in Europe. Henderson is a geography professor at San Francisco State University and Streetsblog contributor.

The 157-page volume starts out explaining why it's so urgent to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and why the key to that is discouraging car use and car ownership. It identifies the concept of "car free" and "car-lite" communities--cities that are designed in such a way to not just make cars unnecessary, but to discourage their use by closing some streets to traffic and restricting parking.

This, of course, is quite the opposite of how most American cities, San Francisco included, were planned in the post-war environment, where governments built wide roads, freeways, and ramps and provided so much free parking it's practically viewed as an inalienable right. But Foletta and Henderson make a compelling case that this has to change immediately. "The World Bank frets that the lack of a universal cooperative global climate policy will result in temperature rises exceeding a disastrous four degrees Celsius within this century--perhaps as early as 2060," the authors write. "Meanwhile, transportation is not only 22 percent of the global total, bust is also the fastest growing sector for global greenhouse gas emissions."

The authors argue that cities around the world must, therefore, study the best examples of what works to reduce automobile use. Planners must then figure out how to emulate whatever they can from cities that have the lowest transportation-derived CO2 emissions. Using pictures, maps and charts, the book attempts to lay out some universally transferable strategies.

The first case study in the book is Amsterdam, which Foletta identified at a book-launch party in San Francisco last Thursday as the city with the best examples globally of how to design livable communities. "GWL Terrein is located in the famously bicycling-friendly city of Amsterdam. Among the developments we have studied, GWL Terrein has gone the furthest to reduce the role of the car in people's lives," the authors wrote. The entire 15-acre brownfield development is designed so it's easy to live there car-free.

Cars are heavily restricted, but not entirely absent. None of the residential units have parking spaces on-site, but there are 129 on-street spaces on the west side of the district, five of which are reserved for car-shares and two for the disabled. It is possible for residents to apply for a parking permit, but they can wait up to seven years. There are other parking options in nearby towns, but prices are high--$100 to $325 per month. Which reflects the true costs to society of parking.

Another case study in the book is Vauban, a well-known car free district of Frieburg, Germany. Like with GWL, there is some parking, but most is located in garages outside the city center, and nearly everyone lives closer to a tram stop than to a parking garage or space. Both cities, as well as others in the case studies, have extensive bicycle infrastructure, public spaces, and employ curbs, bollards and other methods to heavily restrict automobile traffic.

The case studies focus heavily on Northern European nations with a high success rate in encouraging high cycling and pedestrian mode share. The book acknowledges that American efforts to establish a national policy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and auto dependency have "mostly faltered." But it also takes a in-depth look at an exception: San Francisco's Market and Octavia project. With 44 percent of households car free, it wouldn't hold up to European examples such as Houten or Amsterdam, but, as the book rightly points out, it's an impressive example from a North American standard. "The Market and Octavia area is excellent for utilitarian bicycle travel," Foletta and Henderson write. But "the area is also burdened with a substantial share of San Francisco's automobile traffic. Every day, more than 150,000 cars and trucks stream through."

The writers cite the benefits of removing the freeway north of Market Street, the obvious advantage of having such a progressive electorate, and the mandate of California's Senate Bill 375, which requires regional land use and transportation plans to reduce emission from transportation. But it also highlights the way auto usage varies so highly throughout different San Francisco communities.

But the volume doesn't just lay out the different cities, it highlights concepts that can work across cities throughout the world. For example, it explains "filtered permeability." Under this concept, roads are designed in a way that restrict movements by cars, so cyclists and pedestrians are able to walk more directly between destinations, making it a more convenient way to get around in city centers.

The book, obviously, looks favorably on efforts in Europe. But that isn't to say European nations are always on the right track. "Switzerland had a car [political] party," explained Henderson at the book launch, "to figure out how to get more cars." In the 1950s, in fact, transit planners from Europe visited American cities, including Los Angeles, to learn how to build freeways. Fortunately, the Europeans didn't go for it the way most American cities did. But even there the fight continues. "Right now, in Copenhagen, there’s a debate to connect wealthy areas to the airport by a highway tunnel under the city," said Henderson.

Bottom line, the book provides an excellent tool box for Bay Area planners, political obstacles not withstanding, to build a more livable city. About the only criticism of the book: the price. At a whopping $55.95 for the Kindle version and $60.59 for the hard copy, it's not for the faint of wallet. But it's a book any transit or planning agency needs to put on its shelf; it should be required reading for anyone who works in the field or aspires to.