Cross-posted from the Frontier Group.

Vehicle travel in the United States has experienced a resurgence in the last two-and-a-half years, following an unprecedented decade-long per-capita decline in driving. Low gas prices are likely a big reason why; recent increases in incomes and employment as well.

But an additional factor has been relatively unexplored: the effect of changes in credit markets on vehicle purchasing and ownership.

We have been following developments in auto lending for the last two years. Now, with auto lending and the auto industry as a whole at an inflection point, it is a good time to take stock of where we’ve come from and where we might be going.

Resaturating the Market for Cars

In our 2013 report, A New Direction, we argued that many of the factors driving the steady, rapid increases in vehicle travel that occurred during the last half 20th century – what we called the “Driving Boom” – were unlikely to be present in the same ways in the 21st century. One of those factors was growth in the number of Americans who had access to cars.

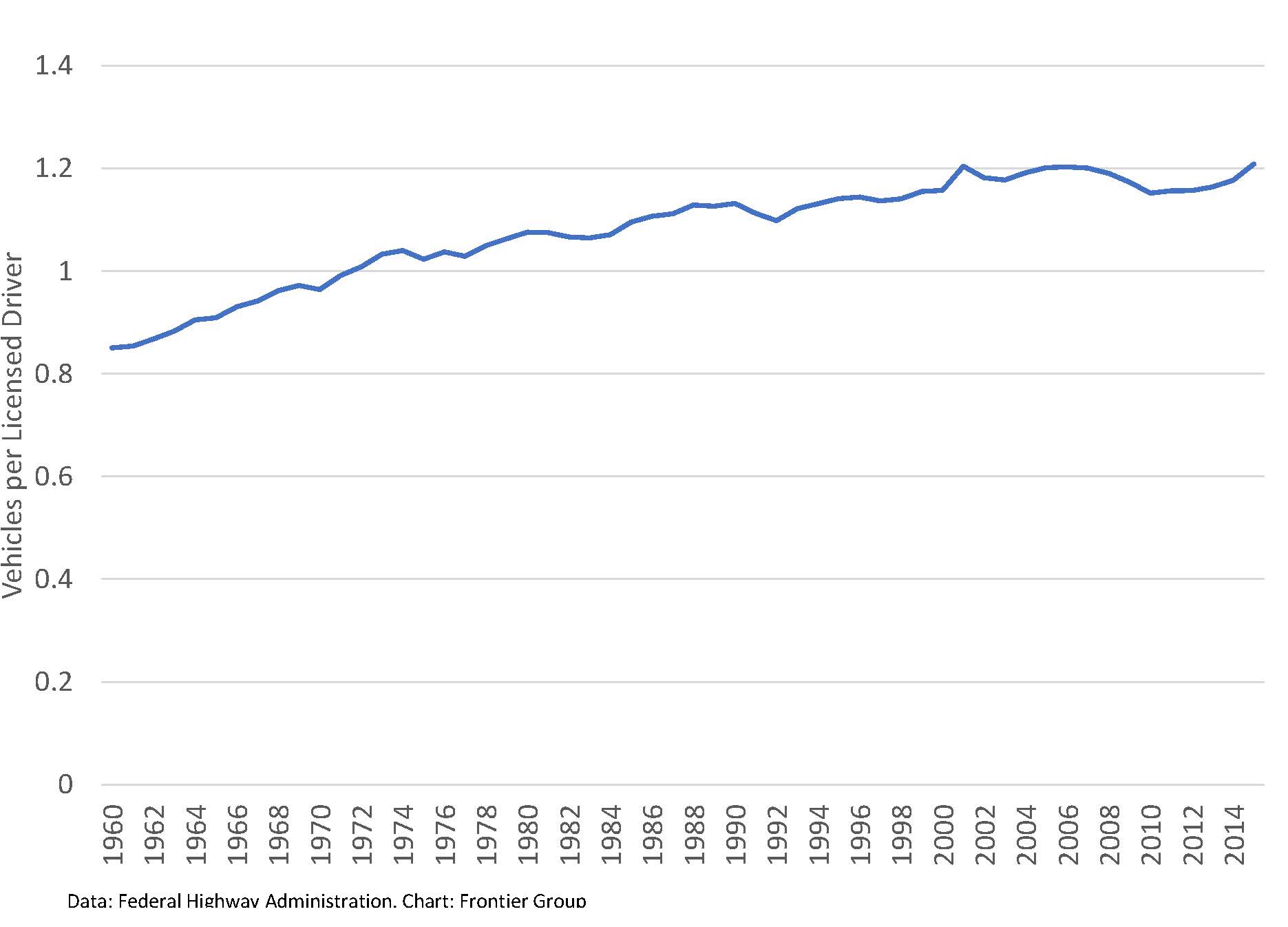

Vehicle ownership increased steadily during the 20th century to the point where, by 2001, there were more than 1.2 registered motor vehicles for every American who was licensed to drive.[1] By then, it was reasonably safe to argue, almost everyone who wanted and could reasonably afford the costs of a motor vehicle probably had one – there was little meaningful room for further growth (aside from population increases). The ratio of vehicles to drivers declined slightly in the years that followed, rose to a secondary peak in 2006, and declined again during the recession years.

Beginning in 2011, however, and accelerating in 2015, the ratio of vehicles to drivers surged to a new peak.

Registered Vehicles per Licensed Driver (data: U.S. DOT)

Why? One explanation is that with incomes rising and unemployment falling, more people who wanted cars could afford them. This is undoubtedly a big part of the picture. But an equally important – and often overlooked – piece is the easy availability of credit for car purchases.

It is unusual that a single paper changes the way I view a subject, but that was the case with a 2014 discussion paper by researchers at the Federal Reserve called Auto Sales and Credit Supply. It concluded that perceived credit market conditions have an influence on auto purchases “as large as factors such as unemployment and income.”

Over the last several years, the auto credit market has been extremely loose, with low interest rates, lengthening repayment terms (translating into lower monthly payments), and a heightened acceptance of risk on the part of lenders. This has contributed to a surge in auto credit – collectively, Americans owed 9 percent more on auto loans at the end of 2016 than they did just 12 months earlier, and the amount of auto credit outstanding now exceeds the previous peak of 2005 by 13 percent when adjusted for inflation.

Boom or Bubble?

If this increase in outstanding credit was built on market fundamentals, it might not be worrisome. (And, indeed, there is an argument that one of the most important changes in auto lending in recent years – the lengthening of loan repayment terms – could be justified by the greater durability of cars.)

But there are plenty of reasons to be concerned that the surge in auto loans has the makings of a bubble. For several years now, stories have emerged out of the subprime auto market of loans being made with little apparent attention to consumers’ ability to repay – stories that sound familiar to anyone acquainted with the conditions that led up to the housing crisis.

As the demand for auto asset-backed securities has continued to grow, lenders have gone farther and farther afield to find borrowers. The auto loans made in the fourth quarter of 2015 performed worse than any other vintage of loans since the crisis year of 2008. In December 2016, the Federal Reserve’s blog warned of “notable deterioration” in subprime lending performance, with households of 6 million Americans now 90 days late or more on their car loans.

All of this sounds quite problematic, and it is on many levels, but it hasn’t yet developed into a crisis. Oddly, in the subprime market, high delinquency rates don’t necessarily spell trouble for lenders or the auto market in general, so long as: a) the interest rates on subprime loans are high enough to compensate for the heightened risk of default, b) repossession is swift, sure and low-cost (the last decade has seen important, um, “innovations” in vehicle recovery), and c) vehicles hold their value well.

If those conditions are in place, subprime lenders and car dealers can even make a profit by selling, repossessing and reselling the same vehicle over and over again, as described by John Oliver in his memorable segment on auto loans on Last Week Tonight. Oliver cited a 2011 Los Angeles Times story that found several vehicles that had been sold and repossessed eight times in a three-year period during and immediately after the recession.

Declining Used Car Values

The problem for subprime lenders, the auto industry, and tens of millions of Americans who’ve purchased cars in the last few years is that vehicles increasingly aren’t holding their value very well. Used car prices are heading downwards, fueled by a glut of high-quality used vehicles coming off of leases and the saturation of the automobile market. At the same time, new vehicles are piling up on dealer lots, with even near-record incentives proving to be of only limited effectiveness in goosing sales.

One of the most oft-stated arguments for why a crisis in car lending won’t be like the housing crisis is that people don’t buy cars as investment vehicles. And that’s true. But while people may not buy cars in the hope that they will appreciate in value, assumptions about how quickly they will depreciate in value affect financial decisions up and down the line – from the monthly lease payments dealers can offer, to subprime lenders’ willingness to take on default risk, to the trade-in value consumers receive when they go to buy a new car.

Already, many consumers wind up owing more on their existing car than they can get in trade-in value – a situation that often results in dealers rolling over the unpaid portion of the previous loan into the new car loan. As early as the spring of 2015, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency was noting that the average loan-to-value ratio of a used car loan had reached 137 percent – and was even higher for subprime borrowers – meaning that many used car buyers were likely “underwater” on their loans from day one. In the first three quarters of 2016, nearly one-third of all vehicles traded in were worth less than the outstanding value of the loan, a new record.

None of this appears to be sustainable, and indeed, there is growing consensus among auto industry watchers that it won’t be sustained. It is as yet unclear, however, whether the auto bubble will deflate with a hiss or a pop, and how much collateral damage it might cause to the rest of the economy in the process.

But the auto bubble does cast a few things into sharp relief that are important for folks who work in transportation policy to understand as we look toward the coming few years.

Disruption Approaching

First, it serves as a reminder that there are millions and perhaps tens of millions of households in the United States without the financial wherewithal to sustain personal ownership of a reliable motor vehicle (and many others for which it is a great financial burden). It is not entirely “the economy, stupid” that determines whether low-income households can “afford” to purchase a car, it is also the willingness of Wall Street to extend credit in ways that put the monthly payment within reach. One can have many views on how this situation came to be and what to do about it, but the fact remains that we have created a transportation/land use system in which millions of people feel the need to purchase something they cannot afford in order to achieve a bare minimum level of participation in the economy and society. That’s absurd, and it is root of the problem. The suburbanization of poverty, job sprawl, and poor public transit service only threaten to make this worse.

Second, we need to come to grips with the fact that there are additional millions, perhaps tens of millions of Americans who purchased vehicles in the last few years whose vehicles may be worth significantly less several years from now than they or their lenders anticipated. How would a crash in used car prices affect the purchasing decisions three years from now of the owner of a brand-new Lexus SUV whose vehicle won’t fetch enough at trade-in to cover the outstanding amount of their car loan? At what point will the “trade-in treadmill” of mounting negative equity stop? As the housing market – which is still struggling to recover a decade after the housing bubble popped – shows, the hangover from the collapse of a credit bubble can persist for a long time. What that hangover might mean for the broader auto market and household access to vehicles going forward is worth exploring.

Third, we should keep in mind that the current situation of rising delinquencies, record incentives for new car purchases, and falling used car prices is emerging at a time when the economy is otherwise doing well. How all of this might play out in a recession is anyone’s guess.

Lastly, we need to note that the potential popping of the auto bubble is playing out against the backdrop of massive changes just now getting underway in transportation technology and the ways that many Americans access mobility – from electric vehicles to shared mobility to the transition to autonomous vehicles. We have no experience with how a dramatic shift in the market for vehicles would affect any of those emerging technologies and services. Now would be a good time to start thinking through the implications.

A Call to Action

The interplay among all of these factors is complex, dynamic and dependent on events and decisions far outside the sphere of transportation policy. But the saga of the auto loan market does reinforce a couple of messages that we have tried to highlight over the years.

The first is that, if you are looking to understand long-term trends in transportation, it’s important to pay attention to underlying factors – demographics, settlement patterns, long-term trends in the structure of the economy, technological developments, etc. – rather than to assume that whatever is happening now will continue indefinitely. Some have suggested that the go-go pattern of car consumption and driving of the last couple of years represents a return to conditions that prevailed before the recession. It is not, and the question of what happens next is far more interesting, more difficult to answer, and more dependent on public policy than it seems.

Second, the experience of the last few years is a reminder that building a less car-dependent transportation system is a necessity not just for the environment, our health and the effective functioning of our cities and towns, but also for the financial health of American households. Relieving as many households as possible of the obligation to own a vehicle is an urgent project. The wealth of new technologies and tools available in transportation – along with tried and true measures such as good public transportation and access to low-cost travel via biking and walking – can provide access to convenient, affordable mobility to a wider variety of people. Public policy over the last 75 years has contributed to creating a country in which most people feel the need to own a car. Smart public policies can help give people other choices.

As we reach yet another inflection point in America’s relationship with the car, it is a critical time for advocates of more innovative, balanced and sustainable approaches to step to the plate. The time may be coming soon when many Americans will find themselves dealing in a visceral and immediate way with the shortcomings of our car-oriented transportation system. We need to be ready with solutions.

[1] This might sound like an absurd statistic, but it’s not – at least not entirely. It includes commercial vehicles, taxis, buses, trucks, cars that are registered but not used, etc. About nine out of 10 U.S. households have access to a car.