Police brutality and racial inequities in criminal justice must be addressed by advocates and agencies aiming to reduce traffic fatalities. That's the key takeaway from a Vision Zero Cities panel yesterday on police violence and traffic enforcement.

Just last Saturday, 15-year-old Jordan Edwards sat in the front passenger seat of a car, leaving a house party in Balch Springs, Texas, when a police officer shot through the windows and killed him. Initial police reports said the officer fired his rifle because the driver was backing toward him "in an aggressive manner." Video evidence later proved that account to be false.

Edwards wasn't killed in a "traffic stop," per se, but his friend's driving behavior was used to justify his murder. He lost his life, as have too many people of color, because a police officer inexplicably responded to a harmless situation with lethal force. And that should concern everyone whose work touches on traffic enforcement.

"Vision Zero cannot be a reason to overly-police black and brown bodies," said Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition Executive Director Tamika Butler. "You can’t ignore the country we live in, you can’t ignore the things that are happening, and you can’t ignore the impacts that occur for folks when they are policed."

In a keynote later in the day, Butler said street safety advocacy "can't lead with enforcement" given the way racism and police brutality are embedded in law enforcement. "I get pulled over all the fucking time for not doing anything but being black... It's not true that if you're not doing anything wrong, you won't get stopped."

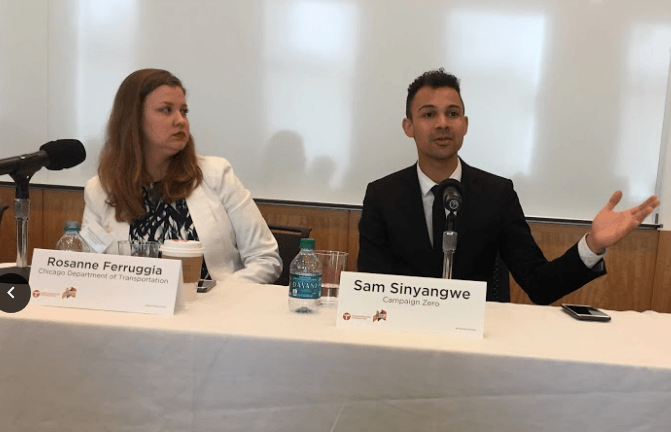

Overall, about 11 percent of police killings -- around 100 people each year -- occur following a traffic-related stop, according to Sam Sinyangwe, an analyst at Campaign Zero, which maintains the most extensive database of police killings in the country. A hugely disproportionate share of those victims are black.

"It can’t be that police are the only thing that we’re thinking about when we say enforcement," said Sinyangwe. "We have to think about what are alternative ways of enforcing traffic violations that don’t involve a police officer -- an armed police officer -- encountering a scared civilian.”

Also on the panel were Chicago DOT Vision Zero Coordinator Rosanne Ferruggia and Captain Mike Crebs from the Portland Police Bureau Traffic Division, who offered insights into how their cities are attempting to uphold traffic safety without reproducing systemic biases in the criminal justice system.

Here in New York City, summonses and citations are often the only metric police officials mention when discussing NYPD's role in Vision Zero. Police do not provide data that shows the effect of enforcement activity on crash rates. NYPD doesn't even release geographic data on summonsing activity. There is no breakdown of traffic stops by race.

In Portland, said Crebs, the police department disaggregates enforcement data by race, as well as whether traffic stops involved a search or revealed any illegal activity, which lets the public assess evidence of bias and unjustified stops.

Automated enforcement is one way to limit interactions with police, but the financial penalties can still impose a disproportionate burden on poor people without posing much of a deterrent for wealthy drivers. For that reason, Crebs said he'd like to make fines proportionate to income. "You take someone who’s on fixed income, charge them $100, their life has been incredibly changed for that," he said.

CDOT's Vision Zero action plan, meanwhile, intentionally excludes citations as a strategy or benchmark for success. Traffic fatalities and injuries are more heavily concentrated in poor neighborhoods and communities of color, but that cannot be used as "trojan horse" for police brutality, in Ferruggia's words. “We have very explicit expectations of what we want in policing, and it’s committing to education first," she said.

Ultimately, for Vision Zero to succeed, governments and advocates have to "ensure that communities are policed equitably," said Sinyangwe. "You can't talk about enforcement without having folks who that enforcement is going to impact shaping that strategy."