A little over a week ago, the San Francisco Examiner ran the Op-Ed: “Fast and cheap: Getting Caltrain to Transbay Terminal … this year." Author Stanford Horn proposed extending Caltrain via Muni’s T/N tracks on King Street and building some more tracks on Howard Street to a platform at the new Transbay Terminal, as a stop-gap measure until the DTX tunnel is built.

He writes:

That goal could be achieved in 99 percent less time, at 99 percent less budget. In fact, the project is so simple that it shouldn’t take more than a few weeks or months to build, involving no new structures taller than a cantaloupe or excavations deeper than a watermelon.

Horn's assertion, that it would be such a simple project that it could be connected up in a few weeks or months, is as silly as it sounds. As Noel Braymer, editor of the Rail Passenger Association of California newsletter wrote: "Oh dear God, where do I begin! There is no way that the Federal Railroad Administration will allow Caltrain equipment to share tracks with much lighter rail transit trains. The reason is, in the case of a collision Muni cars would be crushed if hit by Caltrain!"

To point out another obvious problem: although the track gauge is the same, Caltrain's rolling stock is wider than Muni's. Since Muni uses high-level platforms, that means if you plopped a Caltrain onto Muni's tracks, it would crash into the platform. Furthermore, Caltrain's equipment would likely derail on Muni's track switches. Horn's piece was savaged in the comments section as totally unworkable.

That said, at least Horn is thinking outside the proverbial box. It's also a reminder that railroads didn't always segregate streetcars and heavy rail passenger services. And in many countries, they still don't.

First, there's nothing unprecedented about running heavy rail trains, such as Caltrain, in the street. The alignment that is now used by Muni’s Embarcadero Heritage Streetcar line was actually a freight train route that went through the Ft. Mason tunnel all the way to the Presidio. In fact, the San Francisco Belt Railroad ran trains as far as Fort Mason until 1993. (The Fort Mason tunnel, as Streetsblog readers will note, is part of a proposal to extend Muni rail service that's currently being studied.) And, of course, mainline trains still run down the street on the other Embarcadero, in Oakland's Jack London Square, where the rails are shared by Amtrak trains and freight.

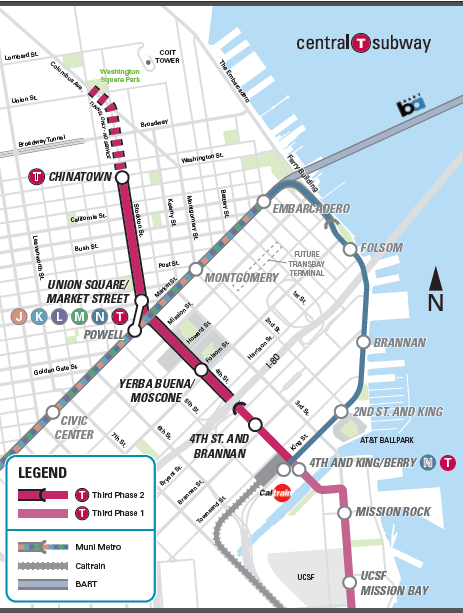

So it's an intriguing idea to extend conventional rail service up to the very tip of San Francisco, considering the right-of-way is there and mostly already in use by trains. Furthermore, the current N/T route along King and the Embarcadero east of Market will be rendered largely redundant once the Central Subway extends the T line to Chinatown next year.

Again, unlike with BART, the track gauge of Muni is the same as the national railway network standard, including Amtrak, Caltrain and other commuter railways, and freight services (4 ft 8.5 in. versus BART’s 5 ft. 6 in. tracks). That means some kind of integration with Caltrain is not totally impossible--just very difficult. In fact, regulatory hurdles are probably a bigger problem than the physical infrastructure challenges. For example, the platform issue could be solved with "gauntlet tracks" that steer the wider trains away from the platform. Or, even simpler, SFMTA could remove the high platforms. There may be other issues, such as the turning radius of the switches, flange depth, etc. But that can be addressed too, albeit over a much longer time frame than a few weeks or months.

And while readers might be tempted to dismiss the idea of integrating Muni and Caltrain, keep in mind that in Europe, there's the concept of a "tram-train." These are streetcars that join the regular rail network, accelerate, and travel out of the city like a conventional train, sharing tracks with standard intercity equipment--that would be the inverse of Horn's idea, and would mean a light-weight streetcar-like train would operate on the Embarcadero tracks, and then continue down the Caltrain corridor. Given Caltrain's already strained capacity and the fact that it will eventually be sharing tracks with High-Speed Rail, this seems even harder to do. The larger point is that some ideas that are dismissed as 'crazy' in the U.S. are actually pretty commonplace overseas.

In the U.S., there is a different regulatory framework for urban rail transit, such as Muni, which falls under the auspices of the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) and the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) versus the national railway network which is controlled by the Federal Railroad Administration. These regulatory differences have largely kept the two modes completely separate. There are places where they share tracks--a few portions of San Diego's trolley system, for example, are used for local freight train deliveries--but they are separated by time (the freight deliveries have to be done late at night, when the trolleys aren't running).

But the regulatory wall between the two types of trains may not be insurmountable. In fact, an advanced signaling system could allow the modes to move together safely--and legally. Technologies such as positive train control, which can override commands of a human operator and stop a train if it is driven past a red signal, make it safe enough to run heavy mainline trains on the same tracks as streetcars.

As we look at expanding services, planners should also look for opportunities to integrate rail services more seamlessly. From a passenger perspective, the benefits are obvious, since it's a way to eliminate transfers, expand services, and make for shorter, more reliable commutes. Furthermore, once the downtown connection to the Transbay Transit Center is complete, there's likely going to be insufficient capacity, and it would help Caltrain's schedule, especially once electrification is completed, to have a few alternate destinations in San Francisco.

The takeaway: Horn is greatly simplifying what would be involved in extending Caltrain on the street. That said, it's certainly worth thinking about better integration of train modes in the Bay Area.