Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

The California High-Speed Rail Authority needs to move more managerial tasks in-house, according to an 87-page report from the California State Auditor, released shortly before this year's Thanksgiving break. "Under its current structure, the Authority’s contract managers experience high rates of turnover and receive little oversight... Although the [Rail Delivery Partner] RDP consultants assist in contract management, they may not always have the State’s best interests as their primary motivation," wrote Elaine M. Howle, California's State Auditor. The RDP, the project's outside contract managerial consultants, was awarded the contract back in 2015 and is led by Parsons Brinckerhoff.

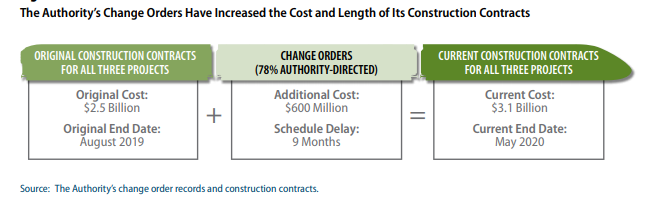

Relying on contracted managers instead of in-house, state employees, explained the auditor, resulted in poor documentation and hundreds of millions of dollars of unnecessary expenses for change orders. She wrote that the CAHSRA failed to heed warnings from an oversight firm about inflated costs.

One example from the report cited a construction contractor that requested "...more than $21 million for unanticipated bridge construction." The oversight firm disagreed with the contractor, estimating a cost of only $7.4 million. The Authority ultimately authorized a change order for $18.6 million—more than twice the amount the oversight firm recommended.

Another big cost multiplier, according to the report, was haste: "...not securing the property on which it intended to build, directly led to cost overruns and project delays," wrote the auditor in the report. "In other instances, the Authority did not sufficiently account for the costs arising from issues it knew it would eventually need to address, such as relocating utility infrastructure from project sites and addressing the concerns of external stakeholders."

The Authority was then hit with charges to disconnect gas and other utility lines to clear the right of way. There was also an issue with parts of the line that parallels Union Pacific's freight tracks--the freight carrier required crash barriers so that if a freight train derailed, it would not incur onto the HSR tracks. The project was also delayed by a 2011 lawsuit (since thrown out) that drove up costs when in 2013 the rail authority was temporarily denied funds to purchase properties.

All in all, "$1.6 billion in contract changes to finish these three projects, pushing its total cost overruns above $2 billion."

The state auditor broke down the revenue streams of the project, including the state cap-and-trade program:

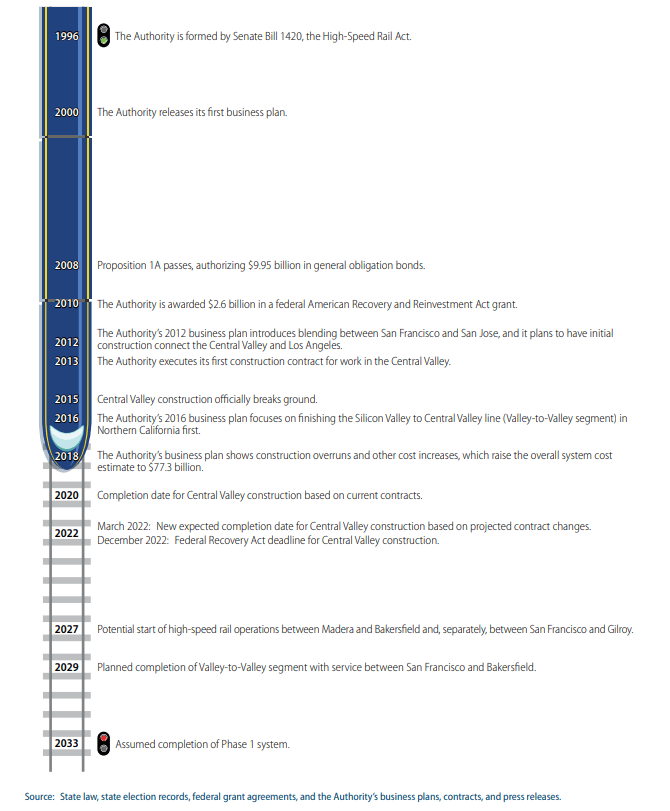

The Authority also receives a continuous appropriation of 25 percent of revenues from the State’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, which is funded by the State’s cap-and-trade program. As of December 2017, this funding stream had provided the Authority $1.7 billion, and the Authority projects it will receive between $4 billion and $4.5 billion in future revenues from the fund through 2030. The Authority also projects receiving an additional $3.9 billion to $11.1 billion if it is able to use federal loan programs or public-private partnerships to borrow against future cap-and-trade revenue. The Authority presented its most recent cost estimate for the system—$77.3 billion—in its 2018 business plan.

Meanwhile, the auditor provided a road-map for how to get CaHSRA back on track. For one, it recommends that the state creates an "independent oversight committee to provide program direction, review costs and schedules, and approve significant change orders..." This type of committee, wrote the auditor, helped get the state's bridge retrofit program back on schedule and on budget:

Our most recent audit report on the retrofit program, released in August 2018, concluded that the oversight committee’s actions had resulted in $866 million in cost avoidance and savings, as well as the avoidance of seven years of potential delays. As a result, the retrofit program was completed generally on budget. We recommended in that report that the Legislature implement similar oversight committees for other large transportation projects that the State undertakes.

The Auditor made the following recommendations for steps that should be taken by the California High-Speed Rail Authority by May of 2019:

- Prioritize contract management efforts by establishing a process for hiring and assigning full-time, experienced contract managers.

- Require CMSU [the 'Contract Management Support Unit'] to establish a schedule to monitor contract manager compliance, and help ensure the unit’s integrity by staffing it with full-time contract managers who are state employees. California State Auditor Report 2018-108 5 November 2018

- Hold contract managers accountable for performing the duties that the Authority’s policies assign to them. The Authority should require and review documentation of the contract managers’ compliance with these policies and related procedures.

That said, the State Auditor's office is, after all, an accounting office--which doesn't necessarily account for political realities. And a few of the report's points must be incredibly frustrating to the Authority itself. For example, the decision to begin construction before lawsuits were fully resolved was because of a stipulation in the Federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, which provided $2.6 billion through a matching grant, that they finish construction by the end of 2022. In order to have any hope of doing that, construction simply had to begin. It's kind of disingenuous to blame the Authority for the way the country provides funds and the litigiousness of California's residents. What were they supposed to do--walk away from the money and do nothing until 2018 while construction and land-costs continued to soar?

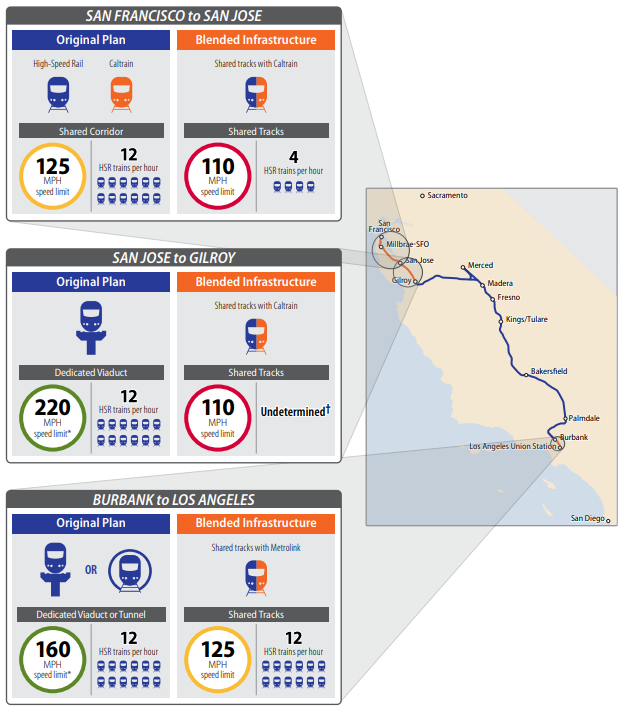

Furthermore, the auditor's office seemed overly critical of the decision to use so-called 'blending' and have HSR share tracks with Caltrain on the Peninsula, at least between San Jose and San Francisco and its effect on runtime. Nearly all high-speed rail systems share tracks with commuter trains when approaching and entering city centers--and many have been upgraded over the years to allow increased speeds. It's, of course, a more complex choice in California since Caltrain and Metrolink, the commuter tracks systems that HSR would have to share, are utterly outdated and require significant upgrades, such as adding electrification.

But the auditor's office seems more-or-less oblivious to these facts, stating that the blended approach requires trains to slow because "...the Federal Railroad Administration sets a speed limit of 125 miles per hour for high-speed trains sharing a corridor or track with other rail traffic and of 110 miles per hour limit if the tracks intersect roads, which can be avoided by elevating tracks over or tunneling under roads [emphases added]. These blended segment speeds are significantly lower than those for dedicated high-speed segments of the system, where regulations allow speeds up to 220 miles per hour."

Actually, raising or lower the crossing's road--rather than tracks--is also an option. This can be added later to permit upgrades and increases in speed and train frequency over time. And Caltrain's new electric rolling stock should be fast enough to permit even blended service on HSR to reach 125 mph, as was in the original plan between San Jose and San Francisco (see chart above). In other words, the auditor's office seems to think that the "blended approach" is a permanent speed and capacity limiter, when it is not. As with the stimulus funds, intractable politics on the Peninsula meant that the only other option to "blending" was to delay construction indefinitely and leave HSR terminating at San Jose.

Without question though, the auditor's office makes some excellent recommendations--and points out additional risks for delay--that state legislators would be foolish to ignore. Let's hope, through an independent oversight committee and structural changes, the California High-Speed rail authority (or whatever other authority it might morph into) can bring qualified managers in-house and stop depending so much on outside contractors to review change orders and other costs.

These seem like reasonable and healthy recommendations not just for HSR, but on other state megaprojects either under construction now or planned for the future.