Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

The California Transportation Commission (CTC) recently held a forum on transportation policy to inform the policy recommendations the Commission makes to the legislature.

The commission's role in funding transportation can help shape state priorities, and the issues they want to hear about could give a window into what they're thinking. Or not. Panelists were invited to address the commission on two main topics: climate change and transit, both of which present huge challenges to state and local governments.

Executive director Susan Bransen pointed out that the commissioners were there to learn. "We do need to more strategically invest," she said, "and I think everyone here agrees on that."

Despite that agreement, one of the panelists, consultant Don Hubbard, who has been working with Caltrans on climate resiliency, said that "the biggest resource restraint in California is consensus." That is, even if everyone agreed that there were a problem, there is no consensus on exactly what the problem entails, nor who would be in charge or what needs to be done.

Hubbard was talking about the challenges the climate crisis has already brought to California. Wildfires, for one example, present some easily understood challenges, such as road closures and the need for evacuations under dangerous, smoke-filled conditions. After the fires are out, there are abandoned cars that need to be cleared, and road repairs are needed. But there's so much more than that. Wildfires destroy vegetation whose root systems stabilize hillsides, leading to future landslide risks. They also bake soil to a hard, impenetrable surface that rain cannot penetrate, increasing flood risk. Burned detritus from buildings and vehicles needs to be cleared away and properly disposed of. Decisions need to be made and funding found to replace housing lost to fires and rebuild roads. And that's just for starters.

Increasingly dramatic cycles of drought and heavy rain, which scientists expect to see in California, raise these risks even higher. Add in rising sea levels from melting polar caps, and the challenges to state infrastructure--roads, bridges, airports, sewers, energy production and distribution--are extreme.

At one point a woman in the middle of the room turned to a neighbor and spoke for everyone: "This is so depressing."

The panelists offered strong recommendations. Training, for example. Training is sorely needed in climate science and adaptation, in best practices, in natural infrastructure solutions, and for transit drivers, who are first responders in emergencies. "We can get paralyzed by the weight of decisions," said Liz O'Donoghue of The Nature Conservancy. Training can help prepare for emergency decision making, and it can also help open minds to creative solutions, she said.

Especially needed is training for mid-career engineers, said Hubbard. He described working with engineers who are so afraid of being sued that they prefer to over-engineer and overbuild infrastructure. This not only adds expense both in the short and long-term, it makes it much harder to incorporate the best practices and new ideas sorely needed if California is to adapt to expected climate extremes. Fear of making mistakes, which he said is not as prevalent in other parts of the world, holds back crucial innovation and experimentation needed under rapidly changing circumstances. "We have to get used to uncertainty," he said.

O'Donoghue pointed out that natural infrastructure solutions--ones that take into account local conditions like shifting wetlands--are less expensive in the long run because they tend to have lower maintenance costs. She recommended that California invest in resilience that doesn't require environmental mitigation at all--that is, that adapts to the natural context from the get-go.

Responses from people in the room tended to prove Hubbard's point about consensus. Dennis Schmidt of Butte County Public Works, which had more than its share of dealing with wildfires last year, said that their engineers rely on Caltrans standards on infrastructure "because we get in trouble if we have to tear out something that we just built." He said that when deliberating about investments, cities "have to choose the cheapest alternative, unless there are specific biological resources we are looking out for." In other words, CEQA's requirements to identify and mitigate for specific environmental impacts are the only method for considering nature in investment decisions.

Which is why O'Donoghue called for the state to develop metrics for ecosystem outcomes, and for transportation investments to be required to address resiliency. Resilience should be a very high bar that every investment has to meet, she said. For example, she said, strengthening S.B. 1, the gas tax that provides transportation investment money, could be done "either through legislation or CTC practices." Current legal language calling for investments to consider resiliency "where appropriate" or "when cost effective" provide a big loophole that needs to be tightened, she said.

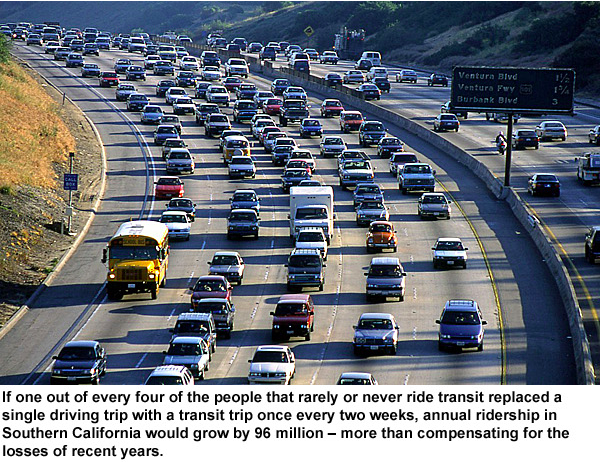

Similar concerns dogged the panel on transit. Clean transportation regulations are bringing a new focus to electric buses, and several panelists talked about the challenges, such as range and energy costs, that they are only beginning to get a grasp of. But CTC chair Fran Inman seemed most concerned about whether clean transit would be used. "Where's our ridership?" she asked, three times.

Michael Pimentel, a legislative advocate with the California Transit Association, agreed that while clean transit regulations are good, they are focusing agencies' limited energies towards technology, and away from simpler core strategies that increase ridership. "Technology is not the silver bullet," he warned.

Transit ridership is indeed falling, all across the country, and blame is variously assigned to ride-hail apps and rising car ownership. Pimentel added another element: the suburbanization of poverty, which has moved low-income people farther away from jobs, where they find it is cheaper to sit in traffic in an old car than to take transit.

But the problems also arise because California is not investing enough in transit, and agencies are not focusing on making service better. Not all strategies needed to increase ridership are within the control of transit agencies, but some are. For example, confusing fare structures and trip planning are part of the problem. This is generally a cross-agency problem, but each individual agency bears responsibility to improve as well.

There are a few transit agencies seeing increasing ridership. What those agencies are doing, according to Pimentel, is some combination of the following:

- Bus-only lanes. Lately Downtown L.A. has been showing how well that works. Doran Barnes, executive director of Foothill transit, was on the panel, and he mentioned that one of his agency's routes used to provide fast service to downtown L.A. Then the carpool lane it used was converted to a toll-plus-carpool (HOT) lane, and now the bus is frequently stuck behind a line of cars. Sometimes passengers look out to see the non-toll lanes moving faster than they are.

- Comprehensive route analysis, such as was done recently in Sacramento, where SacRT took a hard look at its routes and service and implemented some of the additional changes below.

- Frequent service.

- Short travel time--see Foothill Transit, above.

- Reliability.

- Transit priority at traffic signals.

Some strategies are outside the control of agencies, as in the case of Foothill Transit's use of the carpool lane. Others include financial policies, which the CTC might be able to influence. These include commuter benefits--which currently accrue mostly to drivers in the form of parking benefits--congestion pricing, VMT fees (where transit is a viable alternative, stressed Pimentel), and appropriate, demand-responsive parking pricing.

This is just a quick skim of the myriad topics and discussions at the day-long transportation forum. What the CTC ends up doing with all this information remains to be seen.