Note: Metropolitan Shuttle, a leader in bus shuttle rentals, regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog Los Angeles. Unless noted in the story, Metropolitan Shuttle is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

Chances are the Qatar Investment Authority and managers of other sovereign funds, pension funds, and investment portfolios don't care about the parking-space-per-unit ratio of a potential housing development in Oakland or San Francisco. Likewise, they don't care if there are affordable housing units, "missing middle" units for working class families, or if there's a Jacuzzi.

They care about how fast they're going to make a profit off their investment. And if the math doesn't work out, they don't invest, and the housing doesn't get built.

That was a central takeaway of a panel at SPUR's Oakland location Wednesday afternoon about the mathematical realities of housing--and how well-meaning government policies can slowly chip away at development investments in ways that shut down projects before they get started. "Two years ago we got involved with the CASA effort (the Committee to House the Bay Area), put together by the Metropolitan Transportation Commission," explained David Garcia, Policy Director of the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at U.C. Berkeley, and one of the panelists. "As part of this committee we provided technical support," which included explaining the basic math of housing to politicians, advocates, and bureaucrats involved in CASA. What he found out left a profound impression on him: apparently many of the people involved in housing policy in the Bay Area don't know how the math actually works. "That took us a back a bit, for them to say they never heard of development math before."

Impact fees, environmental reviews, affordable housing requirements, etc. may all be well-intentioned policies, but they also whittle away on the return on investment. "Let’s assume we have to build double parking, so fees are $60,000 per unit instead of $40,000--now this project is not getting built," explained Garcia of a theoretical housing development.

Greg Pasquali of developer Carmel Partners gave specific examples of how these fees translate into lost opportunities in the real world. "Yes, we want to create more housing for all the people," he told the group at SPUR. He gave the example of a Bay Area city that wanted to make sure a housing development didn't disrupt a local radio station, so they required that all wires in the proposed apartment building be encased in metal conduit. "And we said, 'but that will cost $3 million extra.' And they said, 'you guys can do that.'" Ultimately, though, added to other fees, it ended the developer's ability to offer a sufficiently enticing return to its investors. "We said, 'no, that will kill the project' - and that killed the project," he said.

One city on the Peninsula said, “just build a library, too," explained Pasquali, as another example. "And a park on the waterfront, on bad soil." That project also died.

Bottom line, explained Garcia, is the "Qatar Investment Authority" or the pension fund, investor, whoever, is free to invest in tech stocks, oil, bonds - whatever it wants to. And that's what they do if housing can't show sufficient returns.

The panelists understood, of course, that cities need some offsets. That's why, they said, developers are looking for other ways to cut costs. Pre-fabricated housing is one way. Pasquali said on one project they pre-fabricated entire walls in Oregon and had them shipped down by truck. There are also companies pre-fabricating bathrooms that can be dropped into place, with plumbing and fixtures already attached.

But Charmaine Curtis of Curtis Development, also on the panel, said pre-fabbed housing can only control costs to a point. "You still have to ship it to the sites," she said. "Modular is not a magic bullet... hopefully there are other technologies that will help bring costs down in a reliable way."

The biggest single problem with controlling costs, they said, is the price of labor, which is getting more and more scarce. "Some of it has to do with Silicon Valley and all the building going on down there," which draws laborers away from Oakland and San Francisco, said Curtis. And then there's the problem of housing being too expensive for laborers to live in the Bay Area. "Only so many people are going to drive from Fresno and Stockton every day. Labor is a huge factor," she said.

Pasquali said solving labor shortages involves going down a whole additional rabbit hole of immigration issues, since a source of additional labor domestically just hasn't been identified in the U.S. "A lot of young people aren’t going into construction. They’re getting college degrees," he said. "There just aren’t as many people there to do the work."

The developers said government officials, meanwhile, can help by making it clear how to get projects approved and what the requirements will be. Otherwise, projects fall through because a "minor" but unexpected demand here or there changes the returns on investment, and then the investors just go away and the project dies.

"As long as you have to raise private equity for investments, they’re looking for the most money they can make," said Curtis. At the end of the day, if rents are high enough, it's still possible to build developments, but as Pasquali and Curtis explained, that means development is going to continue to favor areas of San Francisco and downtown Oakland that have access to BART, where there is sufficient demand from wealthy individuals to live there. That helps improve the math enough to still bring in investments.

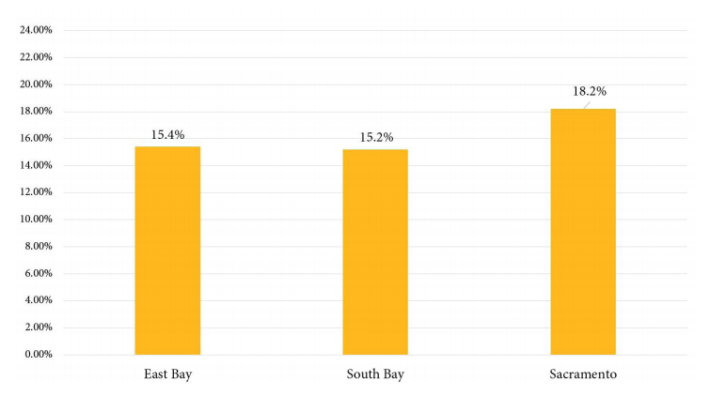

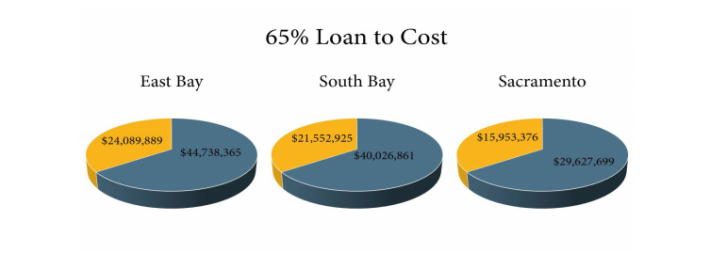

Meanwhile, Garcia's group has put together a paper called "Making It Pencil: The Math Behind Housing Development." It outlines a fictional housing project portfolio called the "Terner Center." The simplified scenario is set up to help people understand how housing math works, by breaking down minimum requirements for bank loans and investments. The hope is if policy makers are acquainted with the math, they'll devise policies that still get cities what they want, without quashing the developments cities need.

For more events like these, visit SPUR’s events page.