Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

Some mornings, if I'm feeling especially sleepy, I open a tab on my browser and play a recording of forest birds singing. It simultaneously calms me and helps me wake up.

A few days ago, I heard the same bird songs. But I couldn't recall starting that soundtrack. Puzzled, I shut off the computer's audio. The singing birds continued. And I realized the birds weren't coming from my computer--they were singing from the window ledges and rooftops of Oakland.

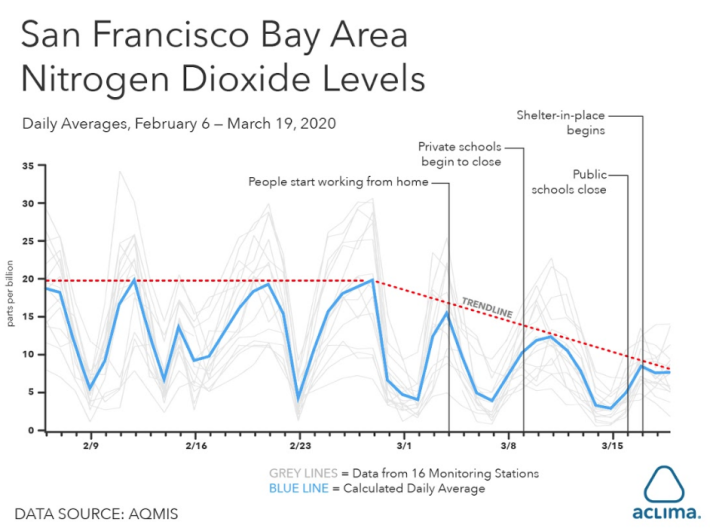

The photo below from a blog post by scientists at Aclima, a company that studies pollution for government agencies, gives a sense of how much traffic has died down during the COVID-19 lockdown.

"With millions of people sheltering in place across the Bay Area, the daily ebb and flow of urban life has come to a sudden halt. The COVID-19 pandemic has upended many patterns and placed tremendous strain on medical, economic, political, and social systems. The corresponding drop in regional traffic, along with reduced industrial and commercial activity, has also led to a significant decline in air-polluting emissions," wrote Aclima's environmental scientists Melissa Lunden and VP of Sensing and Applied Sciences Meg Thurlow in the post.

"While images of empty freeways paint a surreal picture, they also give us an unprecedented glimpse into what happens to the air we breathe when we drastically and suddenly cut emissions," they added.

Along with the drop in air pollution, there has been a drop in background traffic noise--making the city seem eerily quiet. This isn't unique to the Bay Area, of course. Toole Design Transportation engineer Bill Schultheiss posted this view from a corner in the District of Columbia:

“Hello darkness, my old friend

— Bill Schultheiss (@schlthss) April 1, 2020

I've come to talk with you again

Because a vision softly creeping

Left its seeds while I was sleeping

And the vision that was planted in my brain

Still remains

Within the sound of silence”

Gotta say, I like how it sounds pic.twitter.com/YbwMzMFiU3

Listen to the birds. This is what cities could sound like--without so many cars.

"It's an unintentional experiment," Fraser M Shilling, with the Dept. of Environmental Science and Policy at U.C. Davis, said in an interview with Streetsblog. Lowering noise levels from less traffic, and the lowering of human activity on the streets, has invited animals to return. "As traffic volumes go down, the noise levels go down."

How much they go down is still unknown--scientists will be gathering information for some time. But "...the physics of noise means that a car going by on a road delivers an amount of noise, then two cars, four cars, eight cars...the amount of noise doesn’t double. But it increases and then it starts to plateau because the sounds waves aren’t amplifying each other, they are sometimes masking," he added.

That lack of masking that we're experiencing now means more songbirds can hear one another--which encourages more of them to sing. It also makes the songs more audible to humans. The background noise of cities has shifted from the constant hum of millions of car engines to a layering of songbirds.

There isn't much hard data yet, however, "I think there’s been enough studies of wildlife, including birds," said Shilling, "Some of them just stay away from cities probably because of the irritating, anthropogenic noise."

This side effect of the COVID-19 lockdown was first noticed in Wuhan, where the pandemic started. "Right now I hear birds outside my window (on the 25th floor). I used to think there weren't really birds in Wuhan, because you rarely saw them and never heard them. I now know they were just muted and crowded out by the traffic and people. All day long now I hear birds singing. It stops me in my tracks to hear the sound of their wings," posted Rebecca Arendell Franks, an American living in China, on social media in early March.

Franks's post was included in 'The Pandemic Is Turning the Natural World Upside Down,' an article in the Atlantic about the damaging effect of traffic noise. Also from the article:

Scientists have known for decades that noise—even at the seemingly innocuous volume of car traffic—is bad for us. “Calling noise a nuisance is like calling smog an inconvenience,” former U.S. Surgeon General William Stewart said in 1978. In the years since, numerous studies have only underscored his assertion that noise “must be considered a hazard to the health of people everywhere.” Say you’re trying to fall asleep. You may think you’ve tuned out the grumble of trucks downshifting outside, but your body has not: Your adrenal glands are pumping stress hormones, your blood pressure and heart rate are rising, your digestion is slowing down. Your brain continues to process sounds while you snooze, and your blood pressure spikes in response to clatter as low as 33 decibels—slightly louder than a purring cat.

Not long ago, coal miners carried canaries because they are sensitive to poison gases--and when they stop singing, it's an alarm to get out of the mine. Perhaps the birds we hear now, in our attenuated, less-polluted city, are a stark reminder of what poisons--both in terms of stressful background noise and toxic pollutants--are ever-present in our environment thanks to the dominance of the automobile.

"I wake here to melodious bird songs, that's how we all woke as humans before we took over the world," said Beth Pratt, Regional Executive Director for California of the National Wildlife Federation, in a phone interview with Streetsblog. Pratt splits her time between Yosemite and Los Angeles. "That's what the earth used to sound like."

In other words, thanks to the horror of the COVID-19 epidemic, everyone will have a chance to hear and experience how our cities could be all the time if we adopted policies and habits that greatly reduce automobile use after the crisis is over.

Modeling predicts that the rates of COVID-19 infections and deaths are soon to peak in the U.S. Americans are facing a horror not seen since WWII. When it ends, let's hope we will remember the quiet beauty that is accompanying this nightmare, and that we will repair the noxious environment we have created in our cities, not just for the birds, but for ourselves.

For further reading, check out Streetsblog Mass's article on how proximity to highways and the long-term lung damage caused by traffic makes people more susceptible to COVID-19 infections.