This article originally appeared on Planetizen and is reprinted here with permission. For more information and resources, visit Planteizen.

Entertainer Will Rogers once noted that, "The United States is the only country ever to go to the poorhouse in an automobile." This has become tragically true for many low- and moderate-income families.

For example, thousands of automobiles regularly line up to receive food bank packages, as illustrated in the photo above.

These are mostly nice SUVs, light trucks and vans, the types of vehicles owned by responsible families living in automobile-dependent communities. Automobile food bank lines are, to a large degree, a self-fulfilling prophesy: Because residents must drive everywhere, they have high transportation costs, leaving inadequate money for other essentials like food, shelter and healthcare, which forces them to depend on charity. Many of these families would not need food bank help if they could cut their vehicle expenses in half, saving $250-500 per month, but that is often infeasible because they lack affordable mobility options. This is one example of the inefficiencies and unfairness of an automobile-dependent transportation system.

For most of the last century, transportation planning has favored automobile transportation over slower but more affordable transportation options. The result is a community where it is easy to get around by car, but often difficult and sometimes dangerous to reach essential services and activities by other modes. This type of transportation system may satisfy the needs of affluent motorists but fails to serve people who cannot, should not, or prefer not to drive, and imposes unfair financial burdens on many lower-income households.

Consider the economics. Although lower-income motorists use various strategies to minimize their vehicle expenses, such as purchasing used vehicles, driving with minimal insurance, and performing their own maintenance when possible, it is difficult to spend less than about $5,000 per vehicle-year to legally operate an automobile. Some motorists spend less some years, but automobiles are prone to unpredictable and sometimes large expenses. For every low-income motorist that spends less than $3,000 to drive an efficient and reliable old car, two others spend thousands of dollars on vehicle payments and insurance premiums, plus occasional unplanned expenses due to mechanical failures, crashes, traffic citations, and fuel price spikes.

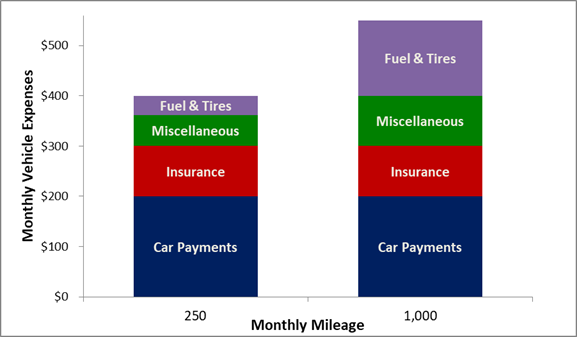

Most vehicle costs are fixed; motorists pay the same regardless of how much they drive (see graph below), so they have few opportunities to save money. For example, a motorist must continue making car and insurance payments, performing scheduled maintenance, and sometimes pay for residential parking, even if they lose their job, so their income and monthly mileage declines significantly. They are stuck.

These expenses are more than many households can afford. Experts define affordability as households being able to spend less than 45% of their total budgets on housing and transportation combined. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistic's Consumer Expenditure Survey, households in the first and second income quintiles (fifth of all households) spend more than 35% of their budgets on housing, so affordability requires that they spend less than 10% of their budgets on transportation.

The table below indicates the portion of total household budgets required to own one or two vehicles, by income quintile, assuming that each vehicle costs $5,000 per year. This indicates that for the first and second income quintiles owning one car is unaffordable, and owning two vehicles is unaffordable for most households.

Described differently, typical lower-income households can afford housing expenses (rent or mortgage) or vehicle expenses, but not both, and owning two vehicles is financially stressful for most households. Of course, many households own more vehicles and spend more on transportation than is considered affordable. This leaves them vulnerable to financial shocks, such as a vehicle failure, traffic collision, or reduced income, which explains why so many families must drive to food banks or require other types of financial assistance.

For vulnerable households, a small vehicle problem can turn into a major financial and legal crisis. For example, a high-interest car loan for an unreliable vehicle, a vehicle crash, being caught driving unlicensed or uninsured, or an unpaid traffic citation can quickly expand to a morass of debt, injury, unemployment, legal strife, and sometimes jail. Default rates on high-risk, high-interest auto loans are increasing, leaving many low-income households with no vehicles, no money, and no credit.

Of course, I'm not blaming those households or ignoring the economic opportunities that owning a vehicle provides. There are certainly examples of disadvantaged households that can justify spending more than recommended on vehicles, for example, to access a better paying job or cheap housing. However, for each of these, you will find more examples of households that are severely harmed by our automobile-dependent transportation system, for example, non-drivers who suffer from inadequate mobility options, and low-income household that go into debt to purchase a vehicle that promptly fails or crashes, leaving them with neither money or mobility, plus injuries and bad credit ratings. The fact that some disadvantaged households succeed in an automobile-dependent community does not mean that it serves everybody.

Maslow's hierarchy of needs would surely rank food, shelter and healthcare above the added convenience and status of driving, but our planning practices give individuals little choice. Most jurisdictions invest far more in automobile infrastructure than in other modes. It is not generally possible to say, "Please don't invest any more on roads and parking facilities for me. Instead, spend my transportation dollars on sidewalks, bike paths, bus lanes and transit services so I have more affordable transportation options."

There are many good reasons to favor multimodal transportation and affordable infill development. Residents of compact, walkable neighborhoods tend to own fewer vehicles, drive less, and rely more on active modes, and so:

- Exercise more, are healthier and live longer.

- Are more economically successful.

- Are more economically productive.

- Have lower traffic casualty risks.

- Generate lower emissions and displace less openspace.

- Reduce the costs of providing public services.

- Are more satisfied with their lives and commutes.

- Have lower housing foreclosure rates.

Some people mistakenly argue that these problems justify even more subsidies for driving, to allow low-income households to access economic opportunities, but that is an inefficient solution. For example, researchers Michael Smart and Nicholas Klein's study, "A Longitudinal Analysis of Cars, Transit, and Employment Outcomes" found that low-income households that obtained a car were able to work more hours and earn approximately $2,300 more per year, which sounds great, but they spent an additional $4,100 annually on their vehicles, so they ended up with less time and less money overall. For many lower-income people, automobiles are an economic trap: they force people to work harder so they can earn more money so they can pay vehicle expenses to commute to their job, making them worse off overall.

It needn't be that way. We can reverse our planning priorities to favor affordable mode and multimodal neighborhood development, in order to create communities where it is easy to live without a car. An efficient, equitable and resilient transportation system must ensure that anybody, particularly those with mobility impairments or low incomes, can find suitable housing in a walkable, transit-oriented neighborhood where it is easy to access basic services and activities—education, jobs, shops and recreation—with affordable modes. This is sometimes called Transit Oriented Development or New Urbanism, and most recently a 15-minute neighborhood, but regardless of what it is called, it offers affordable and diverse transportation options, providing something for everybody, including people with disabilities, children, and anybody who cannot, should not, or prefers not to drive.

I can report from personal experience that by residing in a walkable urban neighborhood it is easy to live car-free and minimize our transportation expenditures: to access local services and activities we spend about a thousand dollars annually on shoes, bikes, bus, plus occasional taxi fares and car sharing.

This is a timely issue. Affordability is an important but often overlooked transportation planning goal. Conventional planning sometimes considers vehicle operating costs and transit fares, but seldom considers total transportation costs and therefore the potential savings provided by more multimodal planning that favors affordable transportation options.

A basic principle of good planning is to "hope for the best, but prepare for the worst." In most North American communities our transportation systems fail to reflect this principle; they favor expensive modes and people with abilities over slower but affordable modes, and therefore ignores the needs of people who are physically, economically, or socially disadvantaged. The box below identifies specific policies and planning practices that contribute to automobile dependency, and therefore higher transportation costs. Planners have a responsibility to identify the harms and inequities that result from these practices, and to identify reforms.

This is ultimately about opportunity and freedom. Conventional policies assume that everybody, or at least everybody who matters, wants to live a high-consumption, high-cost, automobile-dependent lifestyle. It ignores the demands of people who need more affordable housing and mobility options, due to low incomes or because they want to work less and devote more time to art, education or family. All we are saying is, give affordability a chance!

Todd Litman is founder and executive director of the Victoria Transport Policy Institute, an independent research organization dedicated to developing innovative solutions to transport problems. Follow him on Twitter @litmanvtpi