Secretary Pete is walking back a statement that some thought suggested the U.S. could switch from a gas tax to a mileage tax as part of the next infrastructure package — but he's already sparked a conversation about the future of the innovative funding mechanism that's unlikely to die down soon.

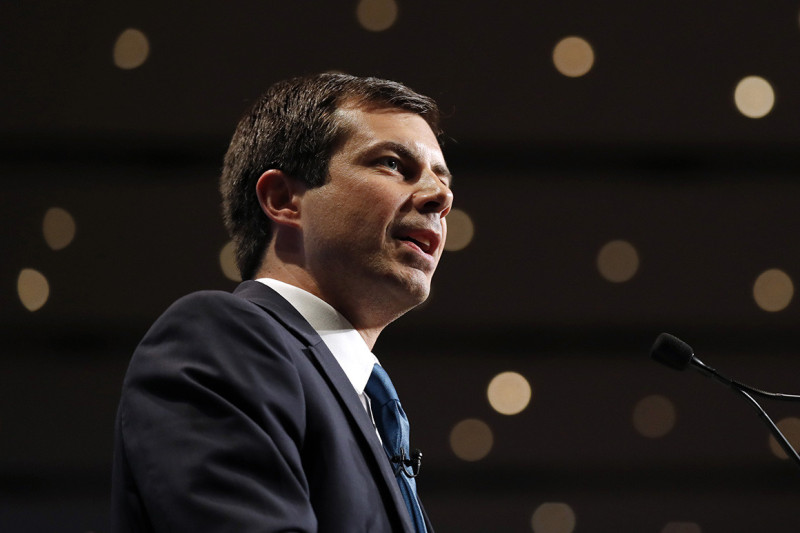

In a rapid-fire interview with CNBC last week, Buttigieg said that a vehicle miles traveled tax (or VMT tax, as it's casually known) "shows promise" among a range of potential solutions to the challenges of funding our roadway network during the rise of electric vehicles, echoing the enthusiasm for the concept he displayed when he made pay-as-you-drive a central element of his presidential campaign platform. Journalists quickly seized on the comment as a sign that the tax might feature in Biden's impending infrastructure bill, a hopeful assumption that was quickly doused by the White House and then Buttigieg himself.

But as the Biden administration hints that taxes on corporations and the wealthy will likely finance many of our roads and transit networks in the coming years, advocates are wondering whether public support for VMT taxes might be on the rise — and whether they might find a place in our transportation landscape, at least at the state level.

A mileage-based tax shows a lot of promise, @SecretaryPete says about funding President Biden's infrastructure package. Revenue generation will most likely come from several different sources. "We've got to think big; it's got to be transformative." https://t.co/QY1JvWXXOA pic.twitter.com/4R2CD6KaZV

— CNBC (@CNBC) March 26, 2021

The concept of a VMT tax has long captured the imagination of safe streets advocates for a simple reason: it's one of the few funding strategies that at least attempts to reflect the costs that excessive driving itself poses upon U.S. roads, as opposed to the societal costs of excessive gasoline consumption alone.

Many advocates argue that while taxing fuel might seem like a good way to charge drivers proportionately to their impact on the planet, it doesn't fully account for the costs of the roughly 38,000 lives lost to traffic violence in America every year. In 2015, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration estimated that car crashes cost taxpayers $836 billion annually — but that was based on 2010 fatality rates, which were about 10 percent lower than they are now. Those costs could conceivably rise even more, especially if deadly-yet-green vehicles like hybrid SUVs or the forthcoming EV Hummer become increasingly popular.

Add in tumbling oil prices and the fact that our federal fuel excise hasn't been increased in 28 years — according to many experts, it may never be increased again — and our default funding mechanism does little to disincentivize the purchase of even the dirtiest cars, much less driving those cars literally everywhere. Americans set all-time records for SUV and pick-up purchases last year, despite sharp economic downturns and historic travel drop-offs caused by pandemic lockdowns. Meanwhile, gas taxes failed to adequately fund the Highway Trust fund even in the 12 years prior to the pandemic, forcing Congress to borrow from general funds provided by all taxpayers to subsidize the maintenance of roads almost exclusively intended for drivers.

A VMT tax, by contrast, would finally flip the myth that motorists pay for the roads they use — at least if it's deployed with care.

"In the long term, a mileage tax makes the most sense to fund infrastructure," said Ethan Elkind, director of the climate program at UC Berkeley's Center for Law, Energy & the Environment. "As we move toward more fuel efficient and electric vehicles, revenues from gas taxes won't support basic maintenance. And there's a fairness principle that people who drive more should pay for more of the road upkeep, although we have to be careful about equity impacts for rural residents who have to drive more, and possibly consider additional factors like vehicle weight, since heavy trucks cause most of the road damage."

Of course, experts are divided on whether rural residents actually drive all that much more than their urban counterparts, as well as whether or not those travel patterns are changing. But equity for high-mileage drivers isn't the only reason experts caution against treating the concept of a VMT tax as a silver bullet.

Some environmentalists have been wary of the funding mechanism because it could flatten incentives to buy fuel-efficient cars and give gas-guzzlers a kickback, unless the tax is tiered to charge the drivers of heavy, dirty cars a little more. In a survey conducted by the Mineta Transportation Institute last year, 49 percent of respondents said they'd support such a "Green VMT" system, compared to 45 percent who said they'd support a flat mileage fee on all vehicles regardless of fuel efficiency.

Others have questioned the potential costs of switching over to a per-mile charge. Because a VMT tax would require installing mileage counters, sourcing smart phone data, or otherwise tracking the distance travelled by every car in America, the Federal Highway Administration estimated that between 5 and 18 percent of revenues from a national pay-as-you-drive program would be spent on collection alone, compared to the relatively cheap overhead of taxing a handful of gasoline wholesalers. (One study even estimated that replacing the fuel tax "could result in collection costs of more than $20 billion annually – about 300 times higher than the federal fuel tax," though it should be noted that the study was funded by a group heavily associated with the trucking industry.)

Taken together, some experts think these two challenges are more than enough to damn any national VMT program in the short run; instead, they recommend a combination of indexing the gas tax to inflation and total fuel consumption, as well as assessing annual fees based on the miles-per-gallon-equivalent rating for EVs.

But while experts like Elkind say that a mileage tax "may not quite be ready for prime time at the national stage," states are already ironing out the kinks in smaller programs. Oregon, Utah and California have all embarked on pilot projects to study pay-as-you-drive taxes, and the next infrastructure bill could empower more communities to try out the innovative idea.

"I'd like to see any federal infrastructure bill leave the door open to a mileage tax, through funding for more state pilots," Elkind added.

No matter how we collect our transportation taxes in America in the coming years, most sustainable transportation advocates will probably agree one thing: we definitely need to stop spending all that money on infrastructure that only benefits drivers.

"The current climate, equity, and aging infrastructure challenges are critical to the funding discussion of any transportation legislation," said Deron Lovaas, senior policy advisor for the National Resources Defense Council. "Congress should invest in clean mobility choices including public transit, walking and biking and EV infrastructure, and consider fixing what’s actually broken with the federal gas tax.”