A consultant by day, Richard Day serves on the board of Renaissance Social Services, an affordable housing provider in Chicago. (The opinions expressed here are his own.) He has no involvement in the planned Weiss Hospital parking lot development.

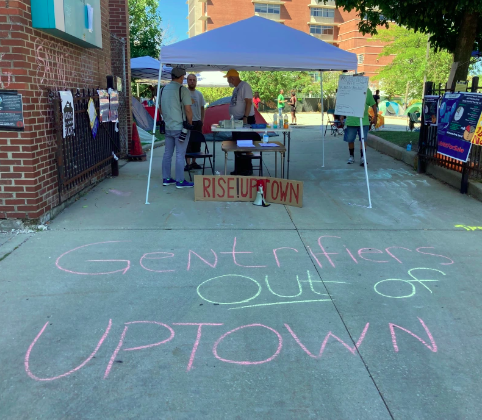

A battle over a new transit-oriented development in Uptown has gone to overtime. Even though the Weiss Hospital parking lot, located at the northeast corner of Wilson and Clarendon avenues, has already been sold and zoning changes approved, activists are currently occupying the site with a tent city in an effort to block construction. Research shows that, generally, new construction helps lower nearby rents and reduce housing displacement (more on that in a bit.) However, the opponents are worried that yet another upscale development in Uptown, with only a few onsite affordable units, will exacerbate displacing pressures in the gentrifying neighborhood.

Developer Lincoln Property Company purchased the parking lot, located adjacent to Weiss for $12 million. (The hospital, at 4646 N Marine Dr, is currently owned by Pipeline Health, but it is in the process of being sold to Resilience Healthcare, which is based in Michigan.) Weiss claims that the funds will be reinvested in the hospital. Under a plan already approved by the City Council, Lincoln will build 314 apartments and 136 car parking spaces on the site, located half a mile east of the Wilson Red Line station. Only eight of those apartments will be rented at affordable rents set by the city and restricted to income-qualifying residents but, in compliance with Chicago’s Affordable Requirements Ordinance, the developer is also making a $3.1 million payment to Sarah’s Circle, a housing nonprofit. Sarah’s Circle has a $16 million project to build another 28 affordable units nearby, which was permitted this week.

The project is designed to encourage transit ridership. It’s about a ten-minute walk from the ‘L’, adjacent to multiple bus routes, and only some tenants will have access to a parking space. According to a calculator developed by the Center for Neighborhood Technology and the Metropolitan Planning Council, almost a million jobs are accessible from the site within a 30-minute transit ride (33 more than than the average TOD project), and the project is expected to generate roughly $9 million in tax revenue for the city over a ten year period.

Last year Lincoln Property Company said studios in the building will rent for $1,600, one-bedroom apartments units will go for between $1,700 and $2,200; and two-bedroom units will rent for between $1,700 and $2,200.

Activists are worried about gentrification and displacement

The activists occupying the lot worry that the additional upscale units will raise housing prices in Uptown, pointing to the paltry number of onsite affordable units. “Every time a new luxury development is built there is a wave of people who come to the neighborhood, and they are often rich, white, young people with disposable income,” said Debbie Baumgartner, an affordable housing leader with the community group ONE Northside. “Each time a luxury development comes in and gets filled with these new faces, there is more reinforcement added to the foundation of gentrification.” Baumgartner pointed to the Wilson Men’s Hotel, a single room occupancy building near the Red Line stop that was recently converted to luxury micro-apartments, as an example of a project that eliminated affordable housing.

Instead, activists would like to see Weiss buy back the parking lot, and offer more healthcare services on the site. Baumgartner suggested an expansion of healthcare services offered by Weiss, such as using outdoor spaces for emergency services. But right now, the activists’ goal is to simply stop the development.

Another opponent of the development, Adam Gottleib of the Chicago Union of the Homeless, told Streetsblog at the tent city today, “We would like to see the hospital use the land as a parking lot, or use it for outdoor health services like COVID testing, which they’ve done before. Really anything except luxury housing that is going to displace people and sit empty for a long time.” He said, anecdotally, members of his group have noted that many of the units in new developments in Uptown are dark at night, suggesting low occupancy.

And while the activists are supportive of Sarah’s Circle, they object to the idea that its programming should be funded by private developers. Instead, they think the city should pay for these services directly. As Mothership Baby Bubba, another leader with ONE Northside put it, “[Sarah’s Circle] should not have to rely on a private developer’s ‘generosity’ for the work they do. Our city and state should fully fund the safety net. Instead, the city continues to show that they value private companies and the interests of the wealthy.”

The case for more housing

Local alderperson James Cappleman (46th), who has often been accused of promoting gentrification and will be stepping down next year, said he sees the issue differently. Cappleman didn’t respond to a request for comment for this story [Update: See the alder’s statement in the comment section of this post], but in a 2021 Q&A he noted that onsite affordable units still charge rents targeted at residents making 60 percent of Chicagoland’s Area Median Income. That means the “affordable” onsite units will still rent for between $900 and $1,100 per month, depending on the number of bedrooms, which means they’ll actually be affordable to middle-class people, rather than low-income or working-class residents.

In contrast, the Sarah’s Circle development, called Sarah’s on Lakeside and located a block north of the parking lot at 4737 N. Sheridan Rd., will charge a maximum rent of 30 percent of the tenant’s income. Mimi Alschuler, Senior director of development for the nonprofit, noted that many of the women Sarah’s Circle serves move in with no income at all, and so pay nothing in rent. The facility will also include a demonstration kitchen, computer lab, and laundry facilities as well as space for case management support.

Cappleman added that he sees important benefits to building the 306 market-rate units on the parking lot site. An observer might see new developments in a gentrifying neighborhood and take note of rising rents in the area, and assume that the new housing is causing the rent hikes. But which came first – new developments, or higher-income people moving into the community? And if the the more affluent newcomers didn’t move into these new developments, would they instead compete with other residents for existing rental housing?

The alder said he thinks higher-income renters would be moving to Uptown in large numbers whether or not new housing is built to accommodate them. As he wrote in a letter announcing his support for the project, “If we don’t provide more apartments to meet the demand for upgraded units in the ward, developers will go after our naturally occurring affordable housing.” That’s exactly what happened to the Wilson Men’s Hotel.

In theory, if developers can’t charge as much for luxury apartments, it’s less lucrative to convert existing housing into upscale units. In a recent Facebook post, Cappleman pointed to a study from the Upjohn Institute that found that new buildings reduce nearby rents by 5 to 7 percent.

ONE Northside isn’t buying that argument. “It’s always easy to find a study that defends a particular position,” Baumgartner responded. She pointed to research from the University of Minnesota that found that new developments in Minneapolis caused higher-end rents to fall, but at the same time rents for lower-cost units rose. If that’s the case, new developments might compete with other high-cost buildings, but still attract more residents that price out renters with lower levels of income.

What does the research really say about displacement and gentrification?

So, as Baumgartner suggested, it seems like a he said / she said situation, with pro-development types citing studies that support their position, and anti-gentrification activists countering by pointing to other reports that back up their worldview, right?

However in 2021, researchers at UCLA reviewed all of the recent studies on new construction and rental costs. They identified six papers, five of which found that new development caused nearby rents to fall. That provides support for the idea that new housing in Uptown will help reduce rent hikes for existing residents.

The one outlier was the University of Minnesota paper referenced by Baumgartner. But the UCLA researchers noted that the U. of M. report didn’t adjust for inflation. That is, rents went up, but at the same rate that prices for everything else rose. When the researchers adjusted for the overall cost-of-living increase, they found that lower-end rents in Minneapolis were “essentially unchanged.”

There is also strong consensus among researchers that across a wider geography, new construction helps reduce rents. That research suggests that adding new housing in Uptown will mean fewer residents will be displaced from other Chicago neighborhoods facing gentrification pressures like Rogers Park and Logan Square. And it’s not just academics who have taken this view. Joe Biden’s White House, and progressive stalwarts like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez are pushing for more housing to help address high costs.

Finally, the current site is a parking lot. It’s not providing any housing right now—affordable or otherwise. It’d be nice to see more than 36 total units of affordable housing coming to Uptown between the Weiss parking lot and Sarah’s Circle projects, but this is a step in the right direction. And, the millions of dollars in tax revenue that come with the Lincoln Property Company development represent more dollars that can potentially be put to use to fund homelessness services across the city.

Let’s make abundant, affordable housing a priority for all Chicagoans

But the activists are right about the larger point. While the Weiss Hospital development probably does pull in the right direction, Chicago’s current approach is manifestly inadequate to address our affordable housing crisis. With a shortage of almost 120,000 affordable units, it would take thousands of similarly sized developments to make a dent. And even if more developments like Weiss help prevent rent hikes in the future, that’s cold comfort for Chicagoans struggling to make rent today.

The UCLA researchers noted that more market-rate housing is only a piece of the solution. Individual developments do help, but the real work needs to be done through broad-based reforms that create more affordable housing including two-flats, courtyard apartments, and new SROs. Chicago’s new citywide plan, We Will Chicago, presents an opportunity to do that. The activists are also correct that the City should spend more to address homelessness directly. ONE Northside and Cappleman both support the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless’ Bring Chicago Home campaign, which calls for a one-time increase in the real estate transfer tax that would affect homes sold for more than $1 million, which CCH said could house 12,000 people for over a decade.

The battle over the Weiss parking lot, including the current tent city occupation, has attracted plenty of attention. While blocking this development would probably do more harm than good, Chicago absolutely needs to do more to fight displacement. Let’s hope activists and alderpersons alike can focus on the bigger picture, and secure abundant housing and supportive services for all Chicagoans.