A motorist killed Andrew Zieman outside of Sherman Elementary on Franklin last November. SFMTA promised a road diet and other "quick build" measures to help reduce speeds and narrow the one-way, five-lane arterial (three running lanes, with two parking lanes). But apparently the lane reduction was quietly removed from the plan over the summer. The culprit, it seems, is an engineering and planning culture that's still using "Level of Service," an arcane and thoroughly debunked metric that analyzes projects based solely on expected traffic congestion at intersections.

First, some background: shortly after Zieman's death, Supervisor Catherine Stefani made it clear that she thinks San Francisco streets need to be safer, especially near schools.

We have a duty to ensure that pedestrians of all ages are able to safely make their way across the City, and we must consider every possible intervention to reduce traffic speeds along this corridor.

— Catherine Stefani 司嘉怡 (@Stefani4CA) November 11, 2021

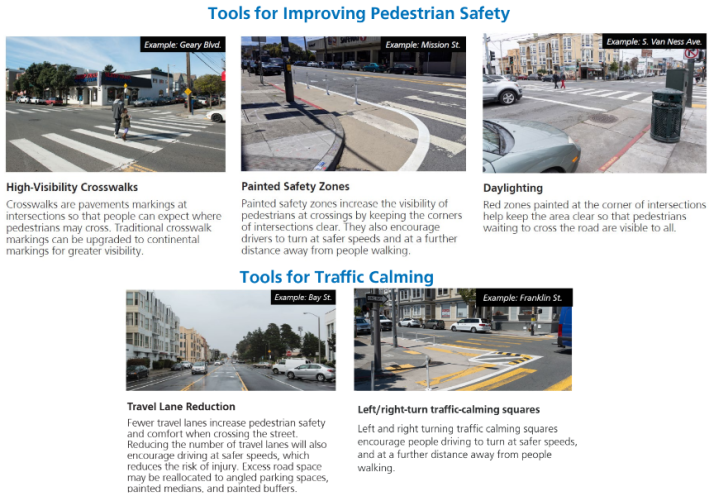

And SFMTA responded with a quick-build plan that included sharper corners, new crosswalks, daylighting, and--most significantly--a lane reduction.

As seen in the above images, SFMTA presented the plans to the Pacific Heights Residence Association back in July. Shanan Delp told Streetsblog that SFMTA planners told him a lane reduction was fundamental to the plan. But then it was pulled. "I got the strong impression a road diet was a logical solution to this problem, so it’s unsettling to see this so casually tossed aside," he said.

Delp, who lives on Franklin and regularly rides his bike or walks with his two small children, demanded to know why. He received this response Tuesday from Shannon Hake, an SFMTA planner:

Thanks for reaching out, and I understand your frustration and disappointment. This is the same process we go through with every Quick-Build project—determining which of our tools works to address the specific needs on a corridor. In the case of Franklin, our original scope included the entire suite of tools in the Quick-Build toolkit (including a road diet), and we anticipated developing a design with any/all of those treatments. Once we began the design process to respond to the community’s needs, we modeled the impacts of all the potential treatments. In the case of a lane reduction, our modeling showed that the impacts to that change were significant and would lead to major queues along Franklin Street and spillover impacts to adjacent streets [emphasis added].

"To say that I'm disappointed in this change is a massive understatement," wrote Delp in his reply to Hake. "When we did our walkthrough a few months ago the door was wide open for a road diet (perhaps even more than wide open, it was emphasized as a no-brainer), and it really breaks my heart that this was pulled from the proposed design. And pulled because of a generalized desire to 'move traffic' that always seems to trump all other outcomes."

So what was it about SFMTA modeling that led to the determination that a lane reduction would cause intolerable traffic spillover? And why does that matter more than the lives of school children and pedestrians such as Zieman? From an internal email also obtained by Delp from SFMTA traffic engineer Alan Uy, written to planning staff:

I assumed vehicles would turn right on Vallejo and onto Van Ness as soon as they realized the road diet. Of course, this degrades the East Bound Left Turn Levels of Service at Vallejo/Van Ness from C to F. There’s no EBLT at Broadway/Van Ness. If these diverted vehicles turned before Broadway, the NB Levels of Service at Broadway/Van Ness would be a worse F. [Emphasis added]

For readers not familiar with Level of Service, it was a legally mandated car-centric metric for engineering of large projects that is behind much of today's traffic carnage. Essentially, focusing on LOS pushes every intersection to be built so traffic speeds during peak periods are nearly the same as in the middle of the night. This practice has resulted in a vicious circle of road widening that increased crossing distances, traffic speeds, and, ironically, traffic congestion throughout American cities. In many places, designs to maximize Level of Service have made it almost impossible to get around without a car. SFMTA head Jeffrey Tumlin helped lead the charge to end mandates for using LOS to measure projects back when he was a consultant. “So a street [ends up] three times wider than it ever needs to be," he told an audience during a SPUR presentation in 2016. "But now walking on the street is a miserable experience and transit will not work, so the street drags down adjacent property values.”

Engineers have used Level of Service in California environmental analyses for years, but in 2013 California passed a bill that was supposed to end the practice. However, it took years to weed out the practice, and it clearly hasn't been quite stomped out yet.

Including, apparently, among engineers at SFMTA.

"Franklin Street is a garbage design and this quick-build project is a once-in-a-generation opportunity to make strides towards making it a livable street," said Delp. "If we fail to seize this opportunity we'll wait for another generation before we make it a street people want to walk on."

Sept. 14, 5 p.m. update. SMFTA communications emailed the following: "It is important to note that no one is killing a project in this email, it’s important to note that safety is the top priority for all of our projects. The public expects us to keep an eye on traffic flow on the city’s few arterial roads even if pure LOS is not the top Key Performance Indicator."