Starting on Wednesday in New York, Transportation Alternatives will host its annual “Vision Zero Cities” conference. In conjunction with the confab, Streetsblog is posting content from the annual journal published by TransAlt. (This article summarizes a more comprehensive report, A New Traffic Safety Paradigm.) We’ll roll them out over the course of the week. Meanwhile, click here for the full conference schedule and to register.

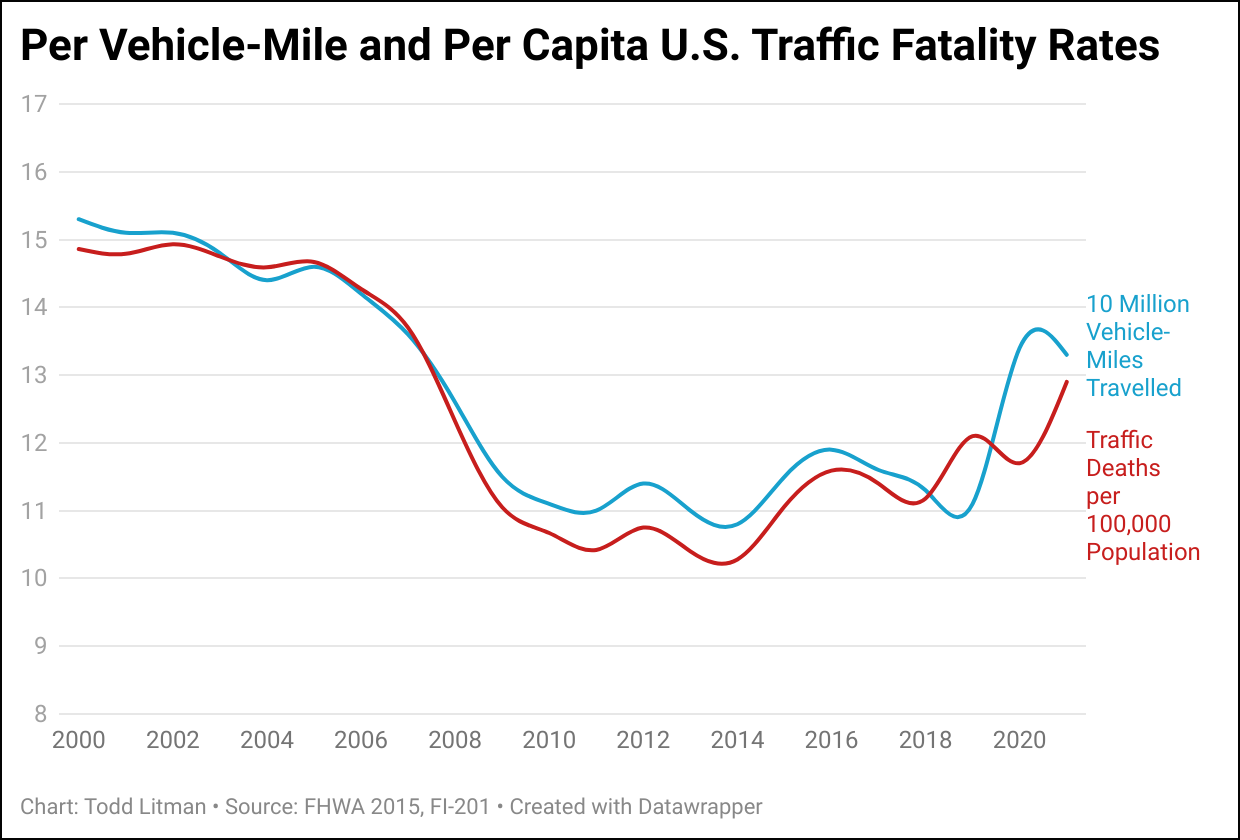

Despite many traffic safety programs, motor vehicle crashes continue to impose large costs in both developed and developing countries. Although traffic casualty rates declined during most of the 20th century, they have increased since 2011 in the U.S., indicating that current traffic safety strategies have fulfilled their potential. New strategies are needed to achieve ambitious safety goals such as Vision Zero. This will require a paradigm shift, a change in the ways risks are measured and potential safety strategies are evaluated. Driving is inherently dangerous, and to reduce total exposure to these dangers, we must reduce driving in the United States.

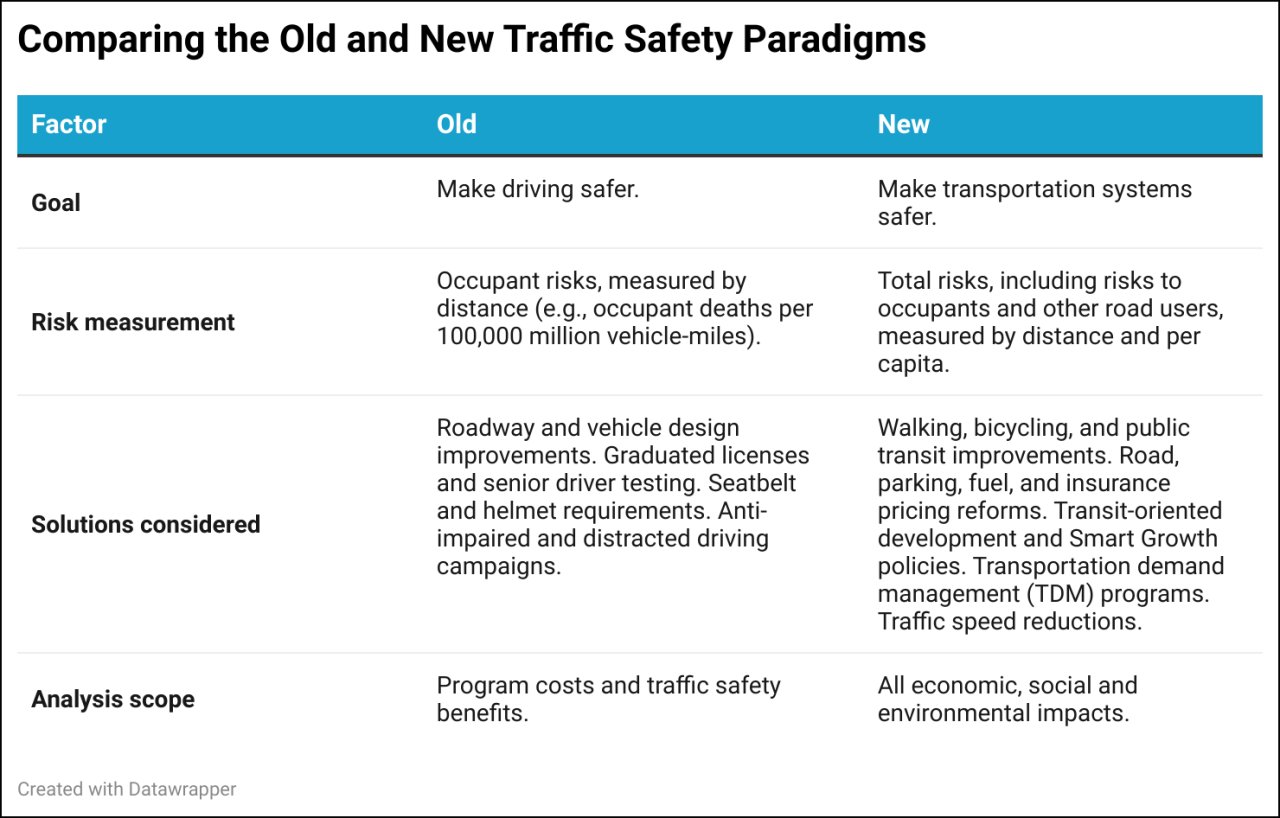

The old paradigm assumed that automobile travel is safe overall and focused crash reduction programs on special risks such as impaired and distracted driving. The new paradigm recognizes that all vehicle travel imposes risks, so exposure, the total amount people drive, is a risk factor.

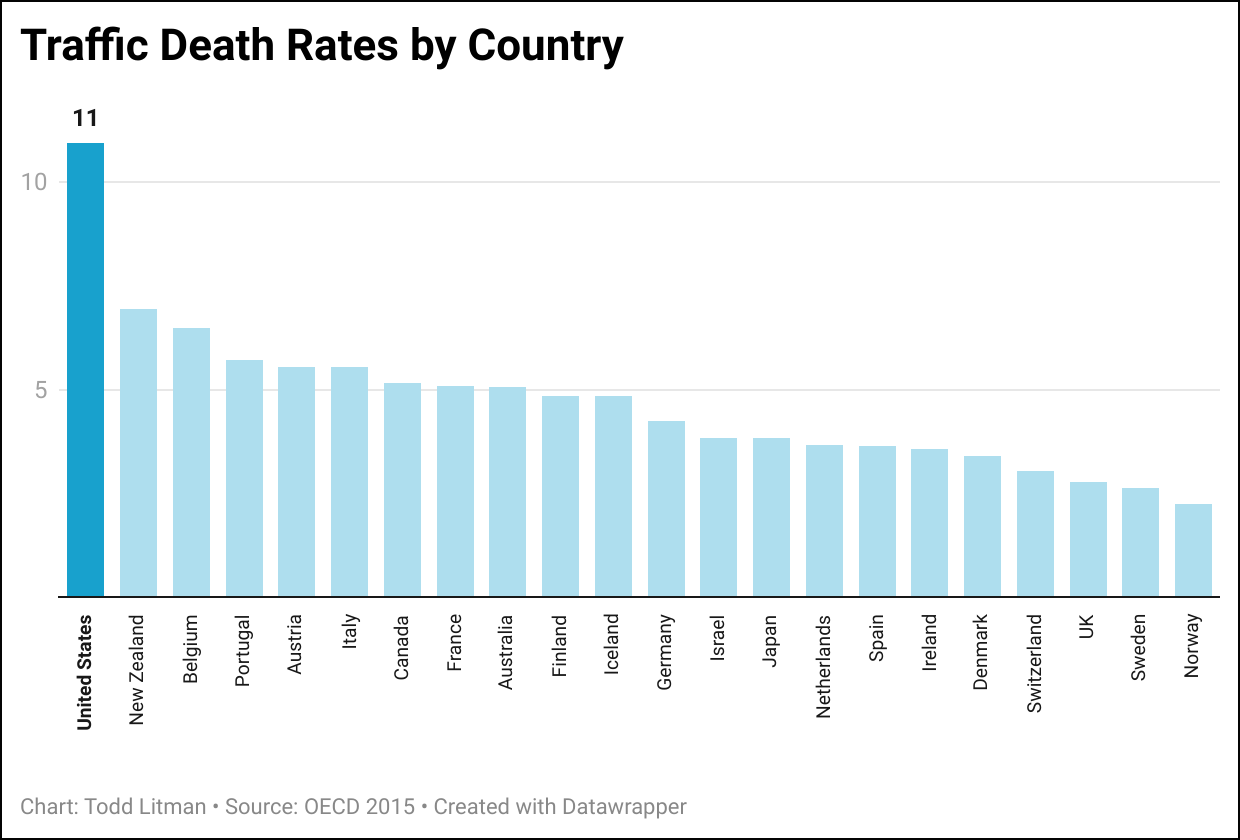

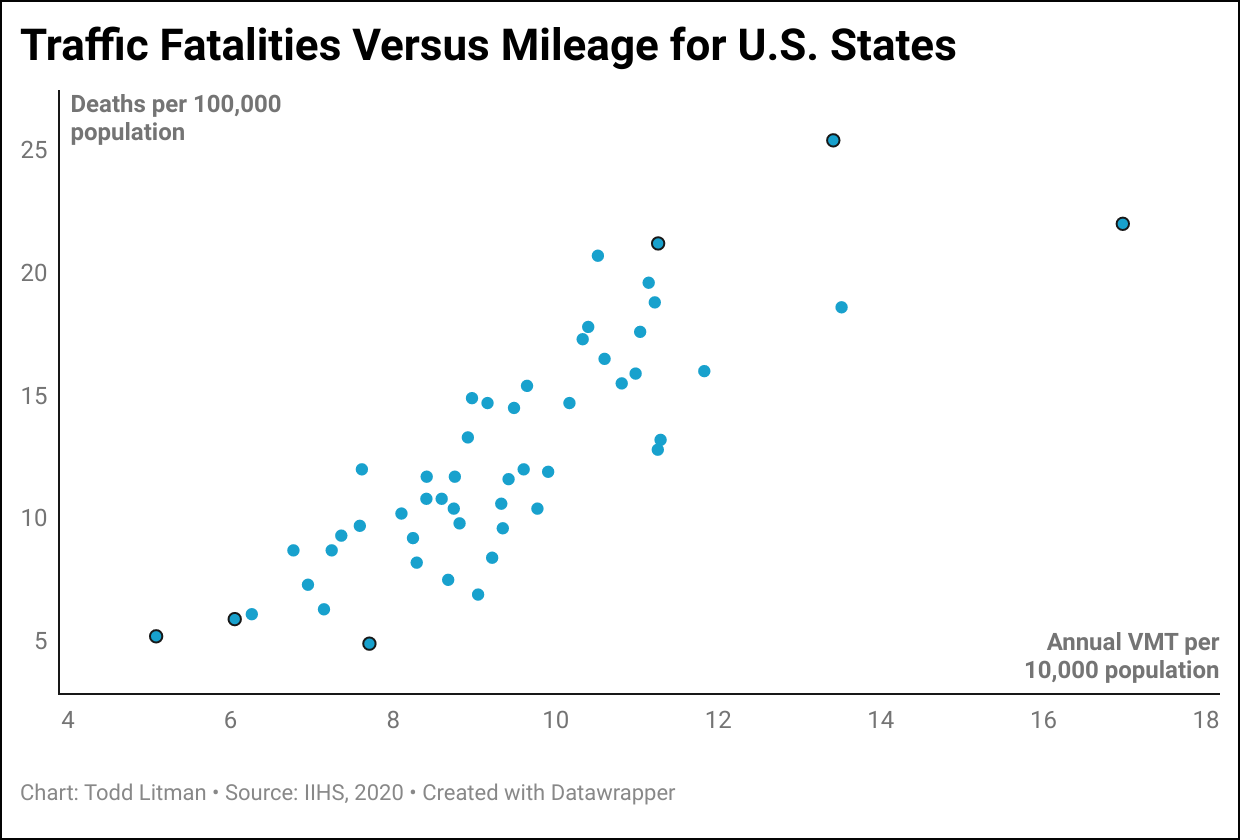

As evidence, consider the large variations in crash rates among U.S. states. Some, such as New York, Hawaii, and Massachusetts have fewer than six traffic deaths per 100,000 residents, while others, such as Arkansas, Wyoming, and Mississippi have more than three times as many. Why? Their residents drive more annual miles at higher speeds than in lower crash-rate states.

Figure 2 Traffic Fatalities Versus Mileage for U.S. States (IIHS, 2020)

Similar relationships are found at other geographic scales: per capita, traffic fatality rates tend to increase with mileage for otherwise similar neighborhoods, urban regions, and countries. Residents of compact, walkable urban neighborhoods have about a fifth of the traffic fatality rates as in sprawled, automobile-dependent areas, and communities that improve pedestrian, cyclist, and public transit infrastructure and shift modes experience significant crash reductions.

This has important implications for transportation planning. It suggests that planning decisions that increase total vehicle travel tend to increase total crashes, and vehicle travel reduction strategies can increase safety in addition to their other benefits.

Table 1 Comparing the Old and New Traffic Safety Paradigms

The current planning paradigm is reductionist, meaning that individual problems were assigned to agencies with narrowly-defined responsibilities. For example, transportation agencies were responsible for reducing traffic congestion, public health agencies for protecting health and safety, and environmental agencies for reducing pollution. Such planning can result in those agencies implementing solutions to the problems within their scope that exacerbate other problems and tend to overlook policies that provide smaller but diverse benefits. The new paradigm supports a more comprehensive analysis that considers multiple goals to identify win-win solutions, policies, and programs that help achieve multiple goals and work in coordination.

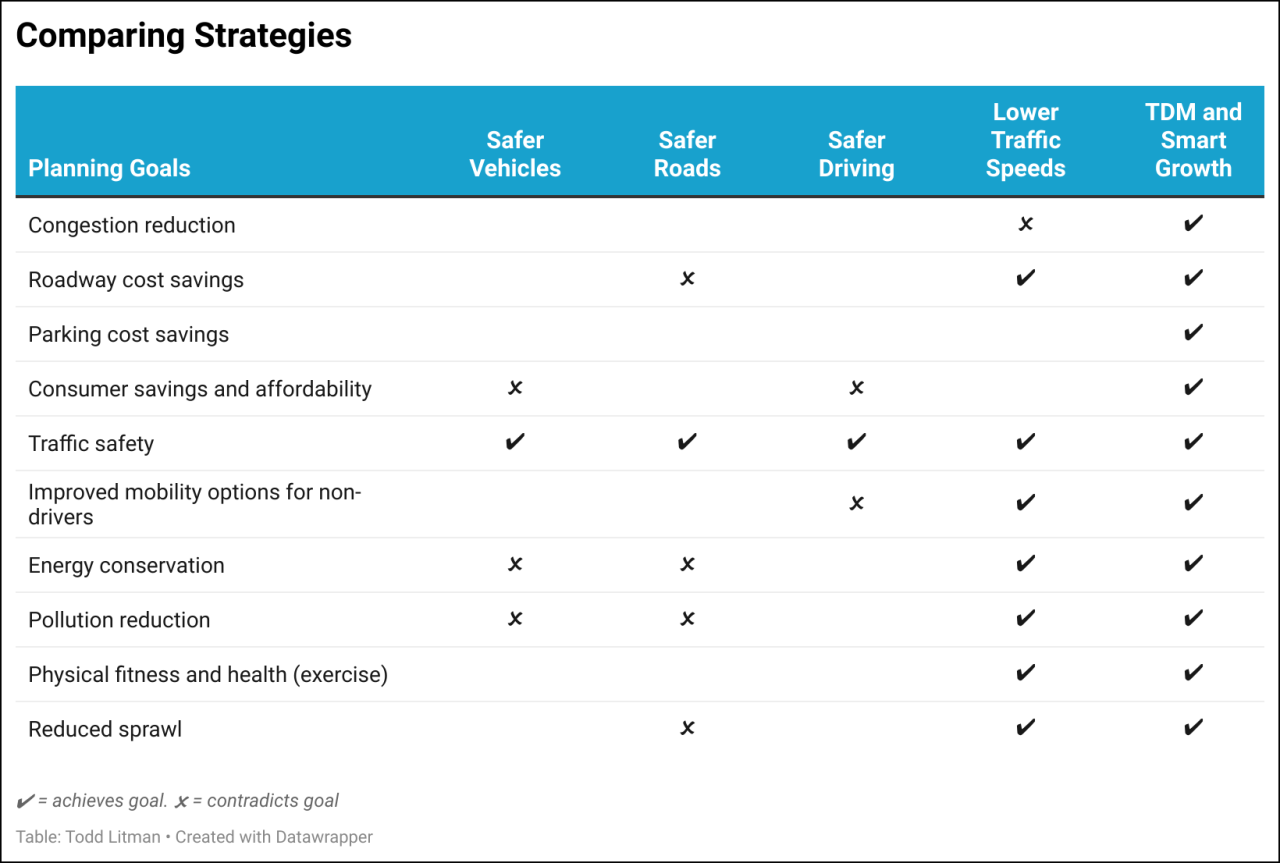

Table 2 applies this concept to traffic safety. The left column identifies various planning goals. Policies that encourage safer vehicles, roads, and driving may reduce crash casualties but achieve few other goals and may contradict some. For example, larger vehicles with airbags and antilock brakes increase occupant safety as well as user costs, fuel consumption, and pollution emissions. Safer roads with grade separation, wider lanes, and more clear-space increase roadway costs and, by inducing more vehicle travel, increase traffic problems. Because they feel safer, wider and straighter roads encourage drivers to take additional incremental risks, such as driving slightly faster or being distracted, a phenomenon called risk compensation. Restrictions on young and senior drivers increase their costs and reduce their mobility options. In contrast, lower traffic speeds, Transportation Demand Management (TDM) programs, and Smart Growth policies that reduce total vehicle travel and create more compact communities increase safety and help achieve other community goals, and so can be considered win-win solutions.

Table 2 Comparing Strategies

More comprehensive safety analysis tends to support social equity goals. Many conventional safety strategies, such as larger vehicles with more passenger protection, and wider roads with fewer intersections, tend to increase walking and bicycling risks. In contrast, lower traffic speeds, TDM, and Smart Growth tend to improve safety, mobility, and accessibility for people who cannot, should not, or prefer not to drive.

This is not to suggest that traffic safety requires eliminating all driving: some vehicle travel is necessary. However, much driving at the moment is not. Surveys indicate that many people would prefer to drive less, spend less time and money on driving, and rely more on alternatives, provided they are convenient, comfortable, and affordable. In addition, many communities have established vehicle travel reduction targets and are implementing multimodal planning, Smart Growth policies, and TDM programs in order to achieve various community goals. These strategies can also provide large crash reductions, saving lives. When all factors are considered, vehicle travel reductions can be a very cost-effective way to increase safety, and traffic safety benefits can be among the largest benefits of vehicle travel reduction policies.

Todd Litman is the founder and executive director of the Victoria Transport Policy Institute, an independent research organization dedicated to developing innovative solutions to transport problems. His work helps expand the range of impacts and options considered in transportation decision-making, improve evaluation methods, and make specialized technical concepts accessible to a larger audience. His research is used worldwide in transport planning and policy analysis.