The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has taken steps to understand how a wider range of bodies are likely to fare when they’re involved in a car crash. But as regulators finally begin to look outside the car, some researchers think it’s time they start thinking about our brains, too — particularly when it comes to kids.

Those questions have long been a fascination for Jodie Plumert, a University of Iowa professor who’s made a career out of studying the psychology of how pedestrians, cyclists, and other vulnerable road users behave on the road, with a particular focus on the most vulnerable ones of all: children with still-developing brains.

“What is it about being an immature organism that puts you at risk for injury?” Plumert said in an interview with Streetsblog. “[Is it] perceptual motor skills, cognitive skills, decision-making skills, even social skills? [What are] the factors, and how do they contribute to why people get killed and injured [in car crashes]?”

In recent years, that interest has taken her into the world of virtual reality. Along with her colleague, computer science professor Joe Kearney, she has asked kids and teenagers to cross countless simulated roads, and found that children consistently struggle not just to decide when it’s safe to enter the street, but to actually get their little bodies moving.

“If you watch adults cross the road, they’ll often cross very closely behind the forward vehicle — but kids don’t,” Plumert adds.”It just takes them longer. The younger the child is, the more they tend delay the initiation of that crossing, and they end up with more close calls, and even getting hit more by virtual cars.”

Those findings may seem intuitive to anyone who’s ever struggled to get a toddler to stop looking at a cloud and hustle already, but they’re largely under-discussed among the people who design the U.S. transportation system. While the Manual of Uniform Traffic Control Devices acknowledges that some people take longer than the industry-recommended 3.5 seconds to cross a 10-foot travel lane in a crosswalk, it doesn’t explicitly acknowledge that many kids take longer than that, or that they deserve a big buffer even outside of school zones where they’re most regularly walking.

Needless to say, speed-focused design standards also aren’t very forgiving of children who might attempt to cross outside of a crosswalk and might struggle to negotiate an even more complex roadway environment — or a kid who might go chasing after a ball and not pause to look both ways before they attempt to retrieve it.

When it comes to vehicle safety, Plumert wonders whether regulators should be doing more to acknowledge the unique psychology of children, too — especially as automated driving technology becomes more and more prevalent. Robocars, after all, might not be able to recognize the sometimes erratic ways that kids sometimes move through the world, unless we take the time to teach them.

“AVs, essentially, use deep learning algorithms to detect what’s an obstacle and what’s not, and to do that, we feed [the system] all these examples into it so it can learn,” Plumert adds. “And one thing we definitely need to feed into it is lots of images of short individuals running out behind or in front of a car quickly.”

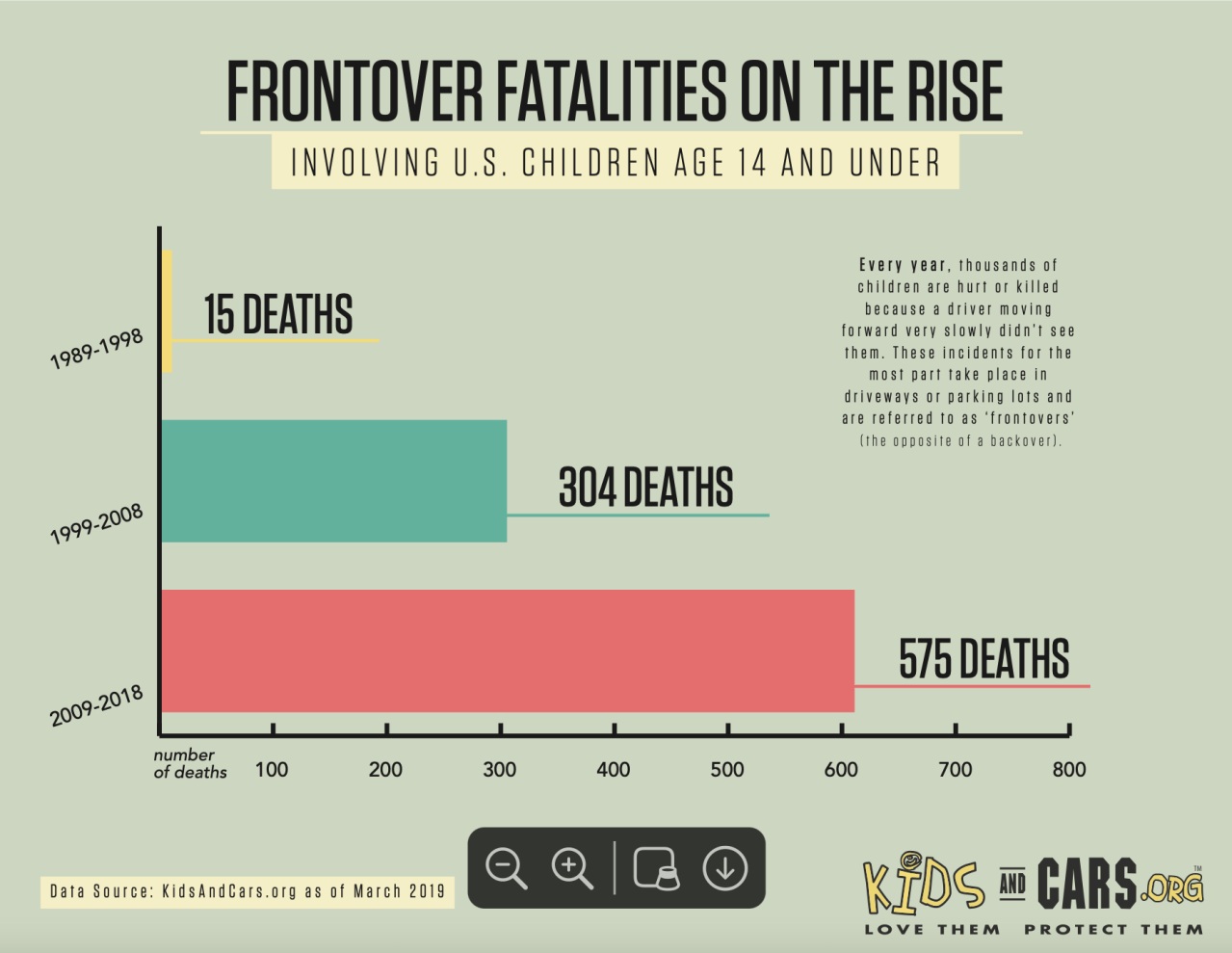

In America’s driveways, though, children are often endangered even when they’re sitting still — because their parents’ and caregivers’ cars are so big that they can’t see a small body in their path. That problem has become even more pronounced since SUVs began dominating U.S. roads in the 2010’s, many of which have such massive blind spots both behind and in front of the car that TV journalists have taken to lining up classrooms full of preschoolers in front of them to demonstrate their safety hazards. Plumert says, though, that the problem isn’t just that kids aren’t visible from the driver’s seat of a Hummer, but that kids might not always move as quickly as an adult when they see a car coming at them — and if that vehicle isn’t equipped with an effective automatic emergency braking system, that could spell tragedy.

“Should these warning systems account for the size of the person behind the car?” she wonders. “Should they, perhaps, give an extra warning if that person is small?”

Plumert acknowledges that education can fill some of the gaps in children’s struggles to stays safe on the road, and she’s done some promising research that demonstrates that parents can have a big impact on crossing behaviors in particular. At the end of the day, though, it’s up to the adults in the room to design streets and vehicles that won’t kill a child if they make a mistake, whether because they’re being egged on by peers, because they struggle with hyperactivity or inattention disorders, or simply because they’re kids who are still learning how to navigate a car-dominated world.

“We design buildings so that they’re ADA compliant and accessible, and we know that when you do that, it makes buildings safer for everyone,” Plumert adds. “If we can figure out more ways to make road crossing safer for kids, we can make it safer for everyone, too — including people who are really good at interacting with traffic.”