The following post originally appeared on Splashpad News and is republished here with permission.

What should be the future of Grand Avenue? Last month, I posed this question to Splashpad News readers. For eleven months, this column has advocated for a grand vision for Grand Ave—a slower, safer street with protected bike lanes, robust pedestrian safety upgrades, and one lane in each direction. But with no city-led survey to clarify community preferences, I decided to fill that gap by asking a simple but essential question: What future do you want for Grand Avenue?

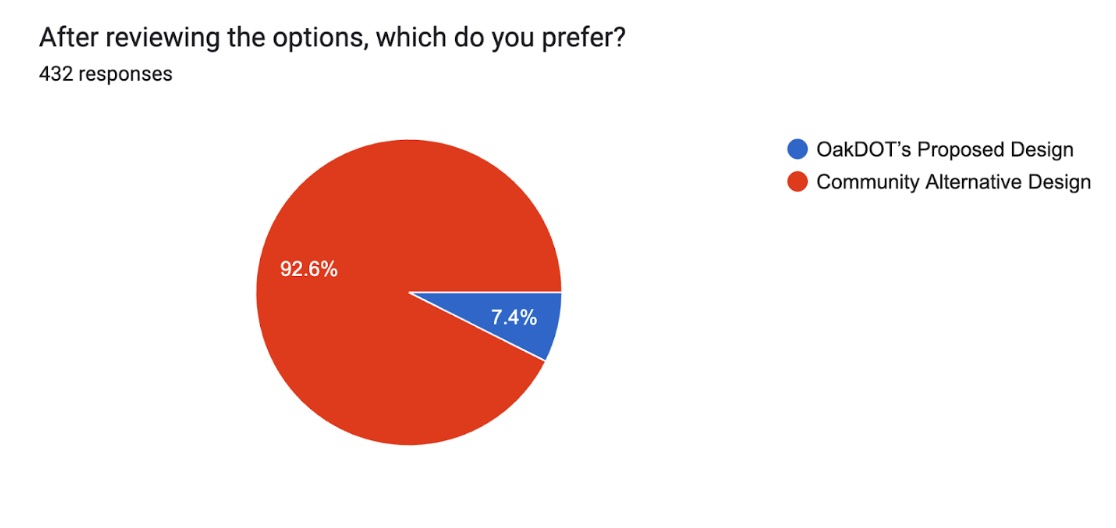

More than 430 people responded to the survey, which was shared through Splashpad News and Grand Lake and Adams Point neighborhood listservs, and snowballed from there. The results were clear: 92.6% support the Community Alternative Design, compared to just 7.4% for OakDOT’s proposal.

The contrast in preference was also reflected in the overall scoring of each design. OakDOT’s design earned an average of 2.04 stars, with only 31 respondents giving it four or five stars. The Community Alternative earned 4.4 stars, with 368 people rating it four or five stars.

Across age, gender and mode choice, support for the Community Design Alternative was consistent

By age:

- 18-29: 95% Community Alternative (18 vs 0)

- 30-44: 94% Community Alternative (210 vs 11)

- 45-59: 91% Community Alternative (83 vs 6)

- 60+: 87% Community Alternative (85 vs 13)

By Gender:

- Male: 92% Community Alternative (209 vs 16)

- Female: 92% Community Alternative (164 vs 13)

- Non-binary: 78% Community Alternative (7 vs 1)

Even among respondents who only drive to Grand Avenue—16% of all participants—87% preferred the Community Alternative. Among those listed driving as one of several modes they use to access Grand (54% of respondents), support was overwhelming at 90%.

These are people who, on paper, might be expected to prioritize speed and traffic flow (also called throughput). But they’re not. They’re choosing a design that emphasizes safety, vibrancy, and clarity over maximizing vehicle flow.

As one driver-only respondent put it:

“I mostly drive through that corridor and would be totally fine with it going to two lanes. This is because I prioritize safety and a more pleasant transit environment for all participants in that area, over getting to Safeway just a little faster.”

Other drive-only respondents put it this way:

“I like that bicycles and cars are separated. It’s much safer for both. I also like fewer lanes of traffic. So many great shops and restaurants are there, but it’s so hard to cross the street. And as a frequent driver, the number of people turning and crossing and biking on the road all in the same space makes it very stressful to drive.”

“I prefer this design because it delivers on the things that actually make a neighborhood corridor feel welcoming: slower, calmer traffic; safer crossings; and more room for people instead of cars rushing through. By removing one travel lane in each direction, this alternative immediately reduces vehicle speeds.”

Even among respondents who live outside the immediate Grand Lake / Adams Point / Trestle Glen area—and who are therefore more likely to drive—support for the Community Alternative remained strong: Among drive-only respondents outside the area, 90% (36 to 3) preferred the Community Alternative; among those who drive as one of multiple modes, support was 91% (103 to 8).

Why such Overwhelming Support?

Reading through 430 responses, three clear themes emerged:

1. Safety for Everyone

Respondents repeatedly emphasized safety, not just for people biking, but for all road users, to address chaos and the double-parking that currently plagues Grand. Physical protection for bicyclists was cited as a key priority.

Respondents voiced little confidence in painted bike lanes:

“Painted bike lanes in the OakDOT alternative will be useless due to double-parked cars and delivery vehicles—we have seen this time and time again in commercial corridors.”

“Cars on this street constantly speed, don’t follow the red lights, and double park where bikes are supposed to get through (which forces us into the road). We need a physical barrier given the dangerousness of this street.”

“I frequently bike with my toddler in this neighborhood and the double parking means I have to merge into perilous car-trafficked lanes! I would really appreciate a protected bike lane here.”

“I don’t ride a bike, but we need serious investment in bike infrastructure if we’re going to be less dependent on cars. This is also more pedestrian friendly.”

“OakDOT’s version maintains the same unsafe conditions.”

“I don’t see the need for 3 lanes of cars. The community proposal seems more open with better visibility for cyclists and automobiles.”

2. Strong Dislike of Back-In Angle Parking

The second major theme was near-universal opposition to back-in angle parking:

“Asking drivers to BACK into parking ACROSS the bike lanes (OakDOT plan) is a recipe for death & disaster.”

“As a driver, I’m very concerned about the risk of hitting a cyclist when backing in and the impatience of waiting drivers. OakDOT’s design will actually decrease my desire to visit merchants on Grand Ave.”

“The back in parking design is still dangerous to bikers. And I don’t think folks understand how much traffic the back in design will create. People struggle to back their cars into a space. Now imagine several cars doing this, holding up traffic and bikes.”

Back-in angle parking was intended as a compromise given the lack of proper protection for bicyclists. While it’s theoretically safer for bicyclists when drivers exit a spot, the maneuver of backing in is likely to create dangers of its own. Indeed, on a corridor as busy as Grand, it’s likely that many drivers won’t even attempt it. Instead, they’ll stop in the travel lane and double-park, just as they do today.

The fact is, any design requiring drivers to cross a bike lane, head-in or back-in, puts bicyclists at risk. Only a protected bike lane avoids that conflict altogether.

3. A desire for a true neighborhood corridor

Respondents repeatedly described wanting Grand Ave to feel like Piedmont or College Avenue: A destination, not a high-speed pass-through.

“Much more likely to create a vibrant and safe Grand, which will better fuel Oakland’s small business community and expand our tax base.”

“The community alternative maintains vehicle accessibility while making Grand much safer, pleasant, and desirable for everyone (drivers included).”

“This is a commercial district that should prioritize pedestrians.”

“Double parking is a big problem on Grand, and the community alternative plan seems to provide less opportunity to do it.”

“The community design also helps slow traffic, which is better for businesses and safer for commuters.”

“Safer, less car-centric, makes the street more of a destination than a passthrough.”

“I find myself avoiding busier streets that have more chaotic driving and double-parking.”

“Gets rid of 2 lanes which encourages speeding in a pedestrian retail area”

“Stops Grand Ave from being a surface street freeway.”

A broader, more representative picture

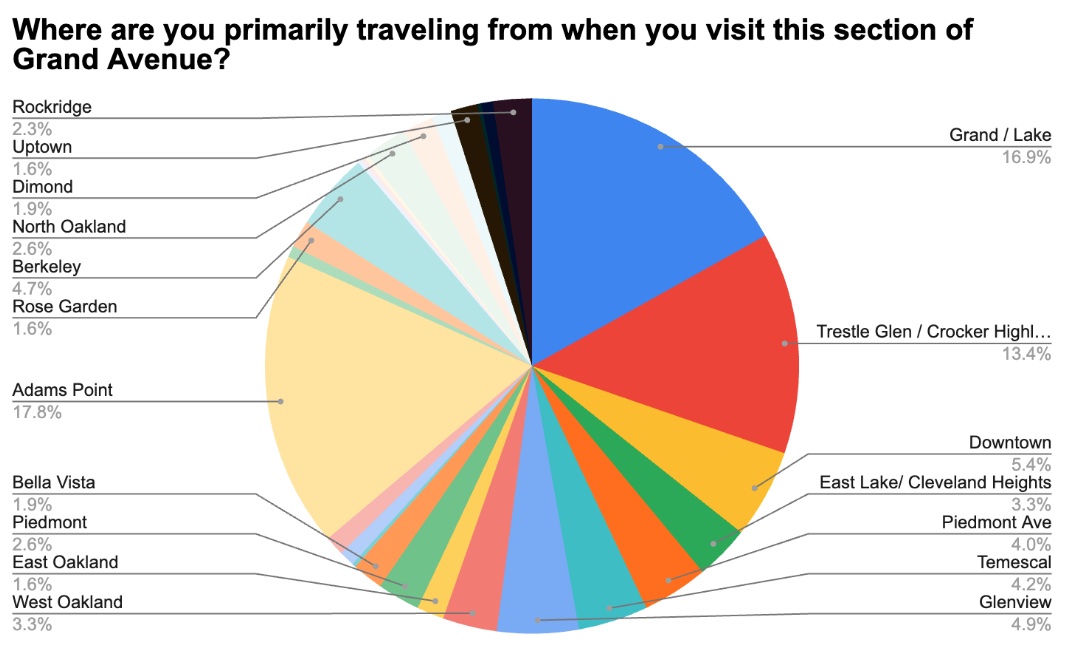

This survey is not a perfect sample of all Oaklanders, but it is far more representative than the city’s outreach to date, which has primarily consisted of the Grand Lake Neighbors meetings. These meetings typically draw about 30 people, many of whom attend repeatedly. Residents from other neighborhoods often don’t know these meetings exist.

This survey drew responses from across Oakland: East Oakland, Downtown, the Laurel, Maxwell Park, North Oakland, Fruitvale, West Oakland, and even Emeryville and Berkeley. These are voices that haven’t been part of the conversation, and they make it clear that Grand Avenue belongs to all of Oakland.

Outreach takes time, and the city does not have a dedicated outreach team. This makes a survey even more crucial for broad engagement and to understand Grand’s use, priorities, and citywide impact.

It’s time to make real tradeoffs

There’s much to appreciate in the city’s current design. It includes important pedestrian upgrades, improves the Grand/Lake Park intersection, and removes a travel lane in the Piedmont direction. But as this survey demonstrates, there is an enormous constituency for more.

Oakland has strong goals around transitioning how people travel (bus, biking, and walking as opposed to cars), climate, and community well-being. The challenge isn’t the goals themselves, but our reluctance to make the tradeoffs required to achieve them. When we pretend those tradeoffs don’t exist, we fall short.

The City’s design feels like an attempt to make everyone happy, to “thread the needle” between competing interests.

But there is no threading the needle. There is no making everyone happy. When that becomes the goal, it simply means the current losers lose more. There are always trade-offs.

And who are those losers? All of us.

Of course, it’s the bicyclists who still won’t get real protection. But it’s also the pedestrians who must continue crossing three lanes of fast-moving traffic. It’s the businesses that could have a true community-oriented corridor rather than a glorified freeway on-ramp. It’s the drivers navigating confusing back-in parking. And it’s everyone who will keep dealing with double-parking.

The only “winners” are the small number of people who won’t be slowed for two or three minutes on their commute. And we should ask: is that really winning?

The Community Alternative Design maintains parking, addressing the core concern of businesses and many drivers. Loading can shift to the Walker lot, freeing up curb space for customers who linger from shop to shop and need parking close by. We can work with delivery drivers to direct them to alternative loading zones and implement demand-responsive parking to truly manage the curb. These improvements can be implemented within the existing budget envelope and address the real problems at the heart of one of Oakland’s busiest and most beloved corridors.

Yes, access to the freeway may be slightly slower, and some additional engineering may be needed. Bike lanes on both sides would be more intuitive, but aren’t feasible if parking is preserved. But if we’re willing to make real tradeoffs, we can unlock so much more. Grand can become a model for commercial corridors across the city.

A path forward

The focus should be on getting it right, not simply getting it done. In light of the survey responses, OakDOT should revisit key elements of the proposed design, but the project should not be delayed.

Grand is a High Injury Corridor adjacent to AIMS College Prep Middle School, two preschools, and the Grand Lake Farmers Market, which draws hundreds every weekend. It is a key connector to Lake Merritt, Lakeview Library, and Astro Park. Grand needs safety upgrades now.

If necessary, those upgrades can be phased. Phase 1 should include the restricted left turn, a road diet in both directions, and a protected bike lane. If, after additional analysis, a full protected bikeway proves infeasible immediately, the paving project can function as a “quick build,” with a clear trigger to return and address the painted bike lane, double-parking, and circulation challenges.

We’ve spent months advocating not only for a better design, but for a better process that acknowledges the large constituency for a safer, slower Grand Ave. We will share these results with OakDOT staff to ensure the final design truly reflects what the community is asking for.

A grand Grand is within reach. I encourage you to read the full set of 430 survey responses here.

***

Arielle Fleisher is a transportation strategist with a unique combination of expertise in public health, design, and urban planning. With a primary focus on transportation, she has worked tirelessly to improve the quality of the Bay Area’s transportation system, including initiatives to make Oakland’s streets safer. She has lived in the Grand Lake neighborhood since 2014.