If a state doesn't build something for over 100 years, it might no longer be very good at it. That was one of the main takeaways during a SPUR talk on Wednesday afternoon about "What California High-Speed Rail Can Teach the Next Generation of Megaprojects" with Boris Lipkin, Vice President of Program Development at STV and former Northern California Regional Director for the California High-Speed Rail Authority. "We've built 119 miles of guideway in the Central Valley," said Lipkin, "That's the largest new rail line built in the U.S. since the Ford Model T was the best-selling car."

Lipkin, who also wrote a study on the challenges of doing megaprojects in the U.S., broke down the six things the state must get right the next time it tries to build a large project.

The first one was something the California High-Speed Rail project actually did get right, relatively speaking, and that's the branding--the message of what the state is trying to do. "To give counter examples, lots of big projects have been on the books for decades only to get cancelled, such as the 'access to the region's core,' a project to build new tunnels under New York's Hudson River, which was cancelled in 2010." He also cited the 2013 Columbia River Crossing between Oregon and Washington, which was also cancelled. "The most famous one is the Cincinnati subway built in 1928," he added. "They built two miles of subway tunnel, but it got cancelled and the tracks never got laid, trains never ran."

On the other hand, California's high-speed rail project was passed by voters in 2008. It's been through multiple administrations both in D.C. and Sacramento. It's been absolutely pommelled in the mainstream press. And yet it survives. Caltrain got electrified as part of the project. And the laying of actual track in the Central Valley is set to begin this year. "The bond passed with 53 percent of the vote and, in the most recent poll, it has 54 percent support, even with everything that's happened." In other words, "the public continues to see its value."

Of course, the project is also notorious for cost overruns and delays. Much of that can be attributed to the on-again-off-again funding every few years as administrations change. "Uncertainty of funding is a major contributor to project complexity," said Lipkin. He explained that instead of just building things in the most efficient way, it became a non-stop calculation of what can get done with the money on hand.

Moreover, the California High Speed Rail Authority was originally set up to study the project, not really to build it. "The agency was never set up to do the job that it eventually got assigned to do," he explained. "In 2011, I had 16 staff; when I left in 2025, we had 500. That doesn’t happen overnight; it requires planning and attention to actually be able to execute." In fact, it took 18 months through the state's hiring system to onboard staffers. As a result, when money finally did become available, it would take that long just to get the people in place to administer the expenditures.

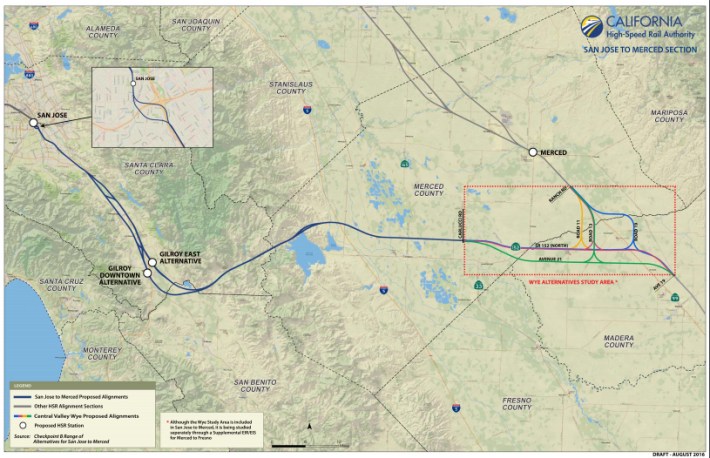

Another problem is that the state never really gave the High-Speed Rail Authority the tools it needed to get things done. Because the Authority had no real authority, land acquisitions turned into protracted negotiations. Local municipalities would demand alternatives be considered beyond what was planned for, such as insisting on "four-lane overpasses" on streets that originally had two lanes. As Lipkin explained it, it should have been one round of alternatives and collecting feedback from cities. "It shouldn't have taken nine years to go through the alternatives process," explained Lipkin.

Of course, lawmakers are working on solutions to this, including streamlining legal hoops that can be exploited to shake down projects. Lipkin attributes some of this to the "pioneer penalty," a phrase he attributed to former Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg. In other words, building the first new substantial rail line in 100 years was bound to expose these structural pitfalls. He hopes, through his experience, the state can do better next time. "If you want an agency to do a thing, you've got to give the agency the power to do that thing.”

For more, be sure to check out Lipkin's full report.

For more events like these, visit SPUR’s events page.