The SF Municipal Transportation Agency released its four-year State of Cycling Report [PDF] this week. While the findings in the report may not be new to those keeping an eye on the growth of bicycling in San Francisco -- which has jumped 71 percent from 2006 to 2011 -- bike advocates say it highlights the city's faltering plans to roll out bike infrastructure in comparison to other cities.

San Francisco's bicycling rate, at 3.5 percent of work trips, ties for second among major American cities with Seattle, lagging only behind Portland's at 6 percent. The city was also recently ranked the second-most "bikeable" city in the country by Walk Score, tying with Portland behind Minneapolis in first. And, no doubt, it has seen an unprecedented roll-out of bike improvements since the bike injunction was lifted two years ago.

But the success of San Francisco's low-cost investments in improvements is all the more reason for the city to catch up to cities like Chicago and New York, which are setting the bar for rolling out protected bike lanes, said Leah Shahum, executive director of the SF Bicycle Coalition.

“The state of bicycling in San Francisco is indeed strong,” Shahum said in a statement, “but it can and should be much stronger by connecting our city more quickly with great bikeways and welcoming more people to biking with a robust bike-share program and great bike parking options. Making San Francisco a more bike-friendly place will help our city be even more successful in reaching our goals of growing jobs locally and improving our overall accessibility, sustainability and public health.”

The SFMTA is working on a strategy to reach the city's goal of increasing bicycling to 20 percent of all trips by the year 2020, but its release seems to have been delayed for months. That goal, set by the Board of Supervisors in October 2010, has been criticized as lofty -- as the SF Bay Guardian pointed out, it would require a 571 percent increase in ridership over the next seven years.

The expectations set in the SFMTA's five-year Strategic Plan [PDF], approved in January, were more tempered, however. The agency's goal is to increase all non-private automobile trips to 50 percent by 2018. Currently, that number is at 38 percent. While that "mode shift" would also come from walking, transit, car-share, and taxi use, "We think half of that can come from bicycle growth," said Tim Papandreou, Deputy Director of Transportation Planning for the SFMTA's Sustainable Streets Division.

"We're at [3.5 percent trips by bike] now, we could get to 8.5, 9.5 percent, which would make us the biggest bicycling mode share in North America," he told Streetsblog. Still, that target would only meet the city's "20 percent by 2020" goal by roughly half.

The "Bicycle Strategy" being developed by the SFMTA, said Papendrou, would lay out how the agency can meet the Strategic Plan's goals over the next six years.

Protected bike lanes and traffic-calmed streets are by far the most effective tool for increasing bicycle ridership, Shahum told the SFMTA Board of Directors yesterday. "There's a lot we can do -- education, enforcement, marketing or promotion," she said. "But the leading cause of behavior change, when it comes to encouraging more people to bike, and encouraging more people to bike safely and respectfully, is infrastructure. It is making safer streets."

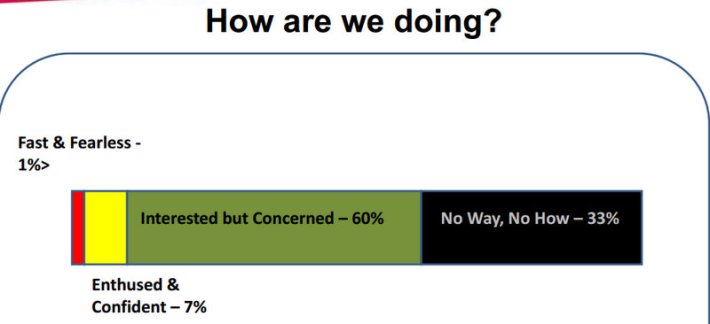

An estimated 60 percent of San Francisco residents are interested in biking more but "concerned" about their safety, said Seleta Reynolds, a planner with the SFMTA's Livable Streets Subdivision.

"These are largely women, they're families, they're younger children, they're older adults," said Reynolds, in a presentation [PDF] to the board. "We know from research done in Portland that where they will ride is in separated facilities or on low-volume, low-speed streets."

"If we build it, they will come, but we're not really building it," she said.

Joél Ramos, an SFMTA board member who visited Copenhagen with agency staff to explore bicycle planning practices, urged the agency to move forward with implementing protected bike lanes. Copenhagen has been building physically separated bike lanes and calming car traffic on its streets for decades, with its bicycling rate now at 35 percent -- a number the city still strives to increase. "So many people regularly bike [in Copenhagen], that it's not even seen as a thing -- it's a utility, it's like putting on your shoes," said Ramos.

Unlike a few comparable cities, San Francisco has set ridership goals, but made few commitments in the way of bike lane miles, aside from a few projects in planning and the SF Bike Plan's 34 miles currently being rolled out, almost none of which are physically separated.

The SFMTA did implement its first 1.5-mile parking protected bike lane on John F. Kennedy Drive in Golden Gate Park, build a two-way bikeway on Cargo Way, and improve the post-protected green bike lane on part of Market Street (which could become car-free and get raised bike lanes in 2016), among other projects. Protected bike lanes are also set to be implemented on Masonic Avenue in a few years and on three blocks of Fell and Oak Streets early next year (that project is set to go to the SFMTA Board for approval in October).

By comparison, Chicago, with just over three times SF's population, plans to have built 22 miles of protected bike lanes this year, bringing the city’s overall total to 33. The city's Department of Transportation installed a protected bike lane on Kinzie Street in six weeks. And that's just part of the city's commitment to building 100 miles over the next four years.

New York City, at ten times SF's population, is set to implement 10 miles of protected bike lanes this year and plans to build 1,800 miles of bike lanes by 2030. Los Angeles County plans to build over 800 miles of new bike lanes in the next 20 years.

The SFBC also pointed out in a news release that San Francisco ranks 18th in per capita funding for bicycle and pedestrian projects among American cities, with $2.55 spent per person. Washington, D.C. spends $9.82 per person, Minneapolis $9.47, Sacramento $8.45, and Oakland $4.95, according to a report from the Alliance for Biking and Walking.

By early next year, SF is set to launch a bike-share system, along with four other cities south to San Jose. Reynolds called bike-share one of the most cost-effective ways to increase bike ridership, typically bringing on a 10-to-15 percent increase in areas where the systems are launched. But the 500 bikes SF will receive (out of the Bay Area's 1,000-bike system) are "not nearly enough," she said.

The SFMTA hopes to double the city's bike-share system in a second phase, and increase it to 2,700 bikes in a third, but there's currently no schedule for expansion. The system is managed by the Bay Area Air Quality Management District, which has said the difficulty of launching a system in multiple cities has curtailed its size and delayed its launch.

The Bicycle Strategy being developed by the SFMTA is promising, albeit delayed. As part of the plan, Papendreou said the agency would likely select three to four "priority bicycle corridors" as well as "connecting neighborhood corridors" next year. Improvements would then be focused over the next six years on closing gaps along those routes, before moving on to others. The goal is to "really bolster up that issue of [having] a connected system," he said.

Papandreou likened the strategy to the SFMTA's Transit Effectiveness Project, in which planners are developing plans for transit improvements along eight selected Muni "rapid" routes before moving on to another set.

"It's not a Bicycle Plan, it's a Bicycle Strategy for our Strategic Plan," said Panandreou, though he did note it's possible a new Bicycle Plan could emerge from it.

Aside from bike lane improvements, the Bicycle Strategy would look at installing bike racks and easing bike-transit trips, with amenities like bike-share stations, secure bike parking at transit hubs, and wayfinding signage for bicycle routes. Many transit commuters are potential bike riders, said Papandreou. Ramos agreed: "I'm on a crammed N-Judah at rush hour, and I'm looking at people, and thinking, 'Why aren't you on a bike?'" he said. "For every bike, there are more parking spaces out there, and more seats on transit."

SFMTA staff expects to present an update on the plan to the Board of Directors in January, though its release was originally expected in the spring. When asked what issues are causing the delay, Papandreou said in an email that agency staff has "been gathering data and developing analysis, framework and prioritization criteria to better link our decision making with the capital improvement planning efforts which are all happening in real time."

Since the Board approved the goals in the Strategic Plan in January, he said, "We have developed a list of key actions for the next two years and determining the level of effort and the funding needed (staffing and capital and operations). Now we're able to develop the accompanying work plans."

As part of the Bicycle Strategy, SFMTA staff is also compiling a report estimating the costs of the improvements needed and identifying potential funding sources, including current revenue and, potentially, new fees. The budget plan would be integrated into the agency's five-year Capital Improvement Plan.

The State of Cycling Report notes that "the current trends in transportation require a rethinking of city priorities and investments if the city is to be successful in creating more active transportation options. Decreasing transportation funding, rising fuel and transportation costs, and concerns about quality of life provide a clear challenge for San Francisco. Recognizing these trends, investing in bicycling presents an opportunity to rethink the city’s transportation investments."

Shahum stressed to the SFMTA Board that quality bicycle infrastructure, like that found in cities like Copenhagen, is one of the most worthwhile investments the agency could make. "We want you to be wildly successful in your Strategic Plan goals," she said. "The end goal is a safer, healthier, more accessible San Francisco."