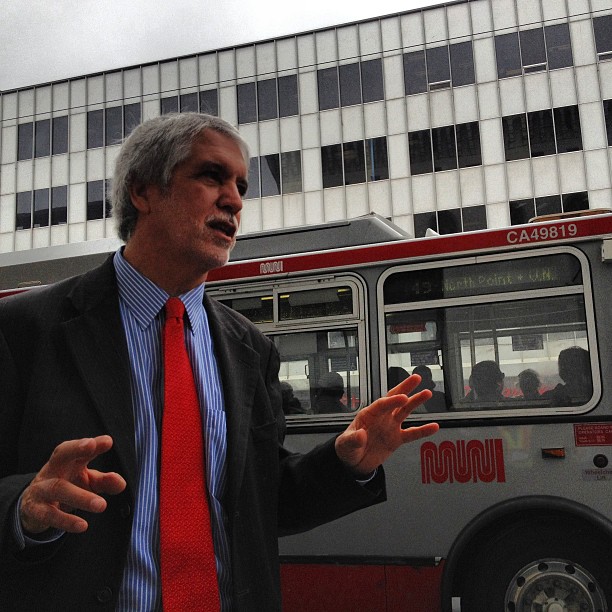

This weekend, San Francisco was treated to a visit by Enrique Peñalosa, the livable streets visionary who spearheaded a transportation revolution as mayor of Bogotá, Colombia by championing ideas like car-free streets, bus rapid transit, and protected bikeways. Peñalosa, who now professes his vision to city leaders worldwide, spoke at Sunday Streets in the Mission and at a SPUR forum.

Sunday Streets, of course, was inspired by Peñalosa's Ciclovia program, which opens many miles of streets every week.

"Why is it so special? Why is it so magical?," Peñalosa asked during a speech on Valencia Street. "It's like a ritual of reconquering the city for human beings... it's always fun to do the things that we are not allowed to do."

In thinking about how cities use street space, Peñalosa emphasizes the importance of equity and democracy as a rubric. "Road space is one of the most valuable resources a city has," he said. "San Francisco could find oil or diamonds underground and it would not be as valuable. The question is how to distribute this road space between pedestrians, bicyclists, public transport, and cars. There is no technical way of doing it. There is no legal way of doing it."

In San Francisco, like most cities, the vast majority of street space is devoted primarily to moving and storing private automobiles. In many neighborhoods, even the sidewalks are used for parking -- an absurd situation Peñalosa took on as mayor in Bogotá.

"Sidewalks are much closer relatives to parks than to streets," he said. "To say that on a sidewalk, there is enough space to park cars as well as for people to walk by, is equivalent to saying that we can turn the main park or plaza into a parking lot -- so long as we leave enough space for people to walk by."

Many of SF's battles over re-allocating street space for people focus on maintaining car parking. To that, Peñalosa says, "We should remember that parking is not a constitutional right."

Peñalosa pointed out that there's no other piece of personal property for which the public provides free space for its storage. When someone buys a refrigerator, for example, the public isn't obligated to provide a kitchen.

"Asking, 'where should we park?,' is like asking where you should put your clothes or your food," he said, eliciting chuckles and applause from the packed crowd at SPUR.

In discussions about people-friendly street redesigns in SF, opponents often complain about an 'undemocratic' process whenever decisionmakers don't yield to their insistence on preserving the car-centric status quo. But, as Peñalosa points out, there was no democratic process behind the decisions to motorize streets that were once a safe domain for children to play in. As Peter Norton has chronicled in his book "Fighting Traffic," today's automobile-centric streets are the result of engineering and propaganda campaigns in the 1920s and 30s, which were met with a violent but long-forgotten struggle.

"Who voted on this?," said Peñalosa. "I would propose that our cities today are very wrong. Not just a little wrong. Totally wrong, because we live in fear of getting killed -- it's become normal."

"Sometimes, we say, it was so obvious that things should have changed," Peñalosa added, pointing to the fight for women's suffrage as an example of an undemocratic state of affairs that was once considered normal.

On most of SF's streets, buses which often carry over 50 people do not get a commensurate slice of the roadway, but instead sit behind private automobile drivers.

"Having a bus in traffic is almost as absurd as having women not vote," said Peñalosa. "Maybe it's not the same, but clearly, if we have a democracy, a bus should never be in a traffic jam. Never. How can you justify it, having big roads for private cars and no exclusive lanes for buses?"

During his visit, Peñalosa took a ride on Muni buses with city officials and planners on Geary Boulevard and Van Ness Avenue, where bus rapid transit lines are planned. The distance between the planned stops on those streets is too close, he said, which will result in slower transit and higher operating costs.

Peñalosa also said there's often a misconception that transit and protected bike lanes are supposed to solve traffic jams by getting people out of cars. To fully address car-clogged streets, he said, car use also needs to be restricted, through efforts like congestion pricing and restricting new parking. He pointed to London as an example of a city with a "great subway system" but that also had to adopt restrictions to alleviate the car crunch in the city center. In fact, Peñalosa said, London has prohibited the construction of parking in downtown office buildings for more than 40 years.

"Mobility and traffic jams are two different problems," he said. "Having transit, subways, and BRT will solve mobility, but it won't solve traffic jams."

Reliable transit systems and protected bike lanes are a fundamental right, said Peñalosa. "We should remember that any child on a bicycle has as much right to road space as the owner of a Rolls Royce or any luxury car."

"Are protected bikeways a right, like sidewalks? I would say so, unless we say that only those who have a motor vehicle have a right to safe mobility without the risk of getting killed," he said, pointing out that a protected bike lane "raises the social status of cycling."

The public planning process in San Francisco is also known for its tendency towards what's been called "hyper-democracy" -- aiming to please absolutely everyone with every single public project. Peñalosa says immediate neighbors of the public right-of-way shouldn't get to dictate everything about its use.

"Do you think it would be democratic, for example, for people who live on Fifth Avenue in New York -- in front of Central Park, in a $20 million apartment -- to have more of a right to decide what to do in Central Park than people who live in the Bronx?," he asked. "I don't think so. There are many things which we are so used to doing that we think they are normal. They are not."

"San Francisco is an emblematic city for the world," Peñalosa said. "Many government officials and engineers and students from [countries like] India are tourists here in San Francisco. Whatever you do here has huge influence in the whole world."

You can see Enrique Peñalosa speak in numerous Streetfilms and in a TED talk. Peñalosa last spoke in SF in 2009.

Stan Parkford contributed to this report.