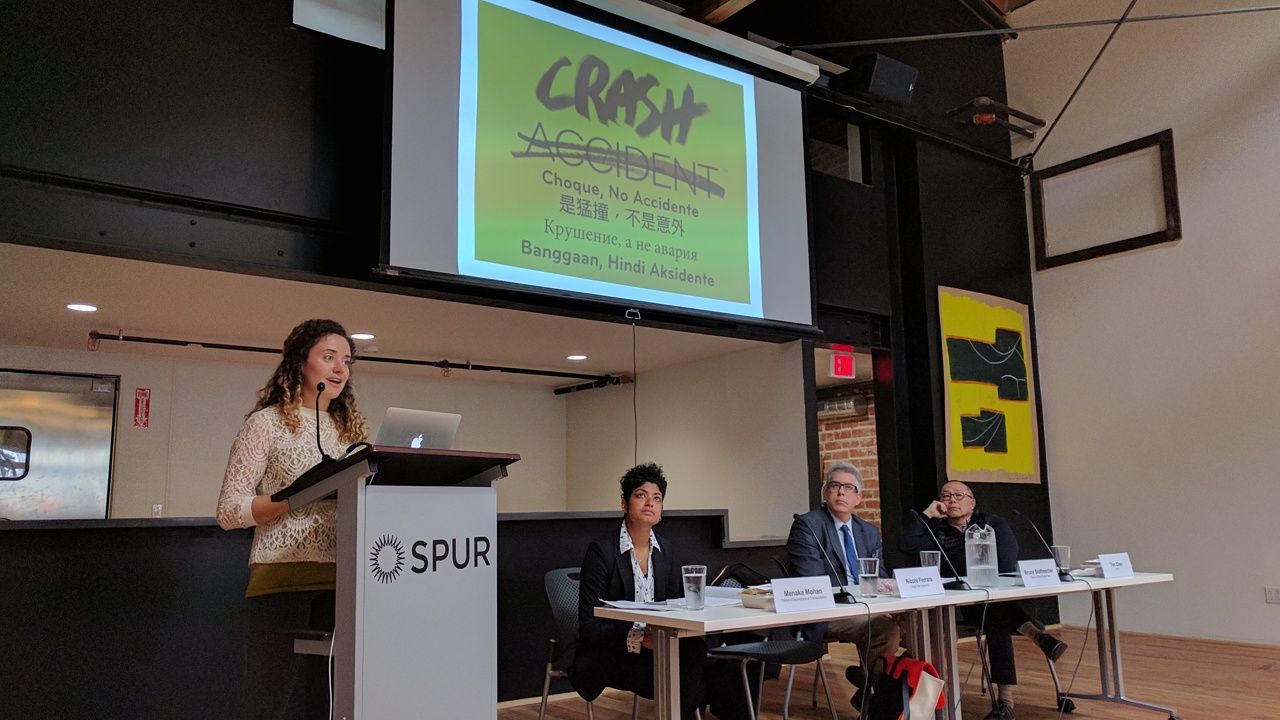

This afternoon, some 40 people attended a forum entitled "Make Me Feel Safe: Achieving Safe Modes of Transportation" at the San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Association (SPUR)'s Oakland center. "Far too many people die on our streets," said Arielle Fleisher, Transportation Policy Associate with SPUR, who introduced the speakers. "Today’s panel is to take a comprehensive look at safety...how do we make people feel safer when biking, walking or taking transit?"

Menaka Mohan with the Oakland Department of Transportation spoke first. She described how her suburban Minnesota upbringing shaped her view of urban planning and safety. She recalled how because of the wide street in front of her house, she felt trapped in the yard. "It was very limiting. We couldn’t go out and play," she said. "Because of that I got very interested in cities."

She talked about the grim statistics for Oakland's streets. "From 2008 to 2014, we had 1,800 fatal or injury causing collisions, with 40 pedestrians killed," she said. She also pointed out that Oakland, like San Francisco or any other city, has a small number of streets that contribute to the majority of crashes. "Two percent of our streets have 36 percent of the collisions...these high-injury corridors are where we see speeding."

Mohan went on to talk about how Oakland's first major street redesign, the parking-protected bike lanes on Telegraph, brought about remarkable improvements in safety. "We removed a travel lane and started a 'road diet,' although communities don't love that word...they use other words for it," she explained. However, she said for the first time in 25 years, there have been no collisions at the street's crosswalks, and that's concurrent with a "...huge reduction in speeding. Before 64 percent of motorists were going above the limit and now most are going the right speed," she said. Another interesting point: businesses were convinced the 'road diet' would hurt their bottom line. Mohan reported a nine percent increase in retail sales on the corridor. While it's impossible to directly link the increase to the road diet and bike lanes, it also completely refutes the assertion--at least on Telegraph--that they hurt business.

Nicole Ferrara of Walk San Francisco started her presentation by asking how many people in the audience have been the victim of some kind of road violence, or knew someone who had, or was caring for someone who sustained injuries. Everyone in the room raised their hands. "Every 18 hours someone in San Francisco is killed or injured in a traffic crash," she said. "Like in Oakland, just 12 percent of streets result in 70 percent of severe and fatal crashes. People don’t turn the corner [from a low injury street to a high injury street] and suddenly become bad drivers...it's that the streets are failing in design."

She also pointed out the profound inequality over which segments of the population are getting hurt and killed. "Black and Latinos, in every city, are more likely to be a victim of a traffic crash. Seniors are 14.5 percent of the population, but account for about half the fatalities," she said. "We see historic inequities that surface in crashes."

She went over the history of Vision Zero, which started in Sweden. "The road system must be designed to anticipate that humans will make mistakes and prevent those mistakes from becoming deadly or resulting in severe injuries," she said, adding that she wants everyone to stop using "accident"--which implies that traffic injuries are inevitable and unavoidable--and start using the word "crash." She also stressed her organization's role in pushing for Automatic Speed Enforcement (ASE), which, she says, avoids some of the obvious discrimination that comes up in police enforcement statistics. Cops, statistically, stop a disproportionate number of African Americans, for example. "A camera sees a license plate, not a face," she said, adding that fines would have to be based on means and the ability to pay.

The next speaker, Bruce Stoffmacher, spoke for the Oakland Police Department (OPD) about its efforts to increase traffic enforcement. "We had no motor traffic patrol for many years, because of the recession," he said. But OPD is trying to improve its traffic enforcement efforts. "Now we have sixteen officers plus two sergeants--two squads on motorcycles who are driving around enforcing traffic laws," he said. And he said they try to focus those patrols on known trouble spots. "Our traffic patrol unit works with people at DOT and looks at collision data," he said. They also respond to complaints via the Oakland City Council. Often lawmakers will hear from constituents and will ask OPD to beef up patrols in certain areas. "We’re being told that on this part of International, for example, people are speeding and running red lights," he explained. In addition, he said OPD is creating a database of surveillance cameras, to help them investigate collisions more effectively. That way, they can check on a database to see if there's a camera at a business on a certain intersection that might have observed a crash, instead of having to look for them every time.

The last speaker was Tim Chan, who works on improving the safety of stations on BART. But first he had some advice about crime. "If you’re on electronic devices please put it down...the biggest reporting of crime is iPhone snatching," he said. He also presented a list of the crimes that occur on BART. "There are many types of security risks, including shootings--once in a long while--but more regularly there are burglaries and thefts." He said one of the biggest problems is people leaving valuable in their cars at the Park n' Rides. There's also "drug use, vandalism , urination, defecation, threats and assaults, access into restricted areas...people entering into our tunnels is a huge problem," he said, pointing out that when people enter the tunnels, it delays the whole system.

So what is BART doing about all this? Some solutions are simple: Chan wants to see the swing gates locked, so the system is more controlled and it isn't possible for anyone and everyone to wander into BART. He also said they want to use reflective surfaces on pillars and walls so it's harder for criminals to hide. And they are replacing bulbs with bright LEDs, so that the system is better illuminated. They also hope to replace the currently opaque elevator walls with glass, so that people--hopefully--will be less willing to urinate inside them. "Right now there are too many hiding places where station agent can’t see what’s going on. Creating more openness is key for us," he said. They also are trying to hire more cops and plan to "...increase the fare barrier heights to five feet. Now it’s so easy to open the swing gates or hop over the barriers."

At the end of his presentation, he returned to some sage advice for BART riders. "Trust instincts about who you sit near, stay in well-lit areas, and don’t leave things in your cars. I wish you a happy and safe journey wherever you go and keep riding transit!"

Indeed, as the panel set out to emphasize, making people feel safe getting around is a multi-faceted endeavor and a big lift. It's going to take persistent, ongoing efforts from officials and advocates alike. But there's no denying, if the Bay Area is going to become friendlier to cycling, walking and transit, all of them need to feel and be safer than they are today.

For more events like these, visit SPUR’s events page.