Power plants used to be located in the middle of cities. Back in the start of the 20th Century, there was no such thing as a high-voltage distribution grid, so small generators were placed right in downtowns. They were often ensconced in beautiful, art-deco buildings that blended with the rest of the street. "But once we were able to raise voltages, we got rid of central locations for power plants, because they were pretty polluting," explained Robert Ferry, co-founder of the Land Art Generator Initiative (LAGI), a Seattle-based non-profit, during a presentation this afternoon at SPUR's Urban Center in San Francisco. "And we got the power plants we think of today."

He's referring, of course, to coal, nuclear, gas, and even renewable energy plants that are huge, located outside of cities, in ugly and sterile structures, surrounded by towers and distribution wires. So Ferry and LAGI's co-founder Elizabeth Monoian realized that when it comes to renewables, which don't belch out poisonous smoke, maybe it's time to bring power generation back into the city. They started to challenge supporters of renewable energy to rethink the power plant. "We encourage artists working alongside engineers and scientists. We held four international design competitions, and our fifth launched a couple of days ago," said Monoian.

The idea is to integrate modern windmills, photo-voltaics, and other renewable energy technologies into parks and other urban spaces.

The LAGI web page explains it this way:

The goal of the Land Art Generator is to accelerate the transition to post-carbon economies by providing models of renewable energy infrastructure that add value to public space, inspire, and educate—while providing equitable power to thousands of homes around the world.

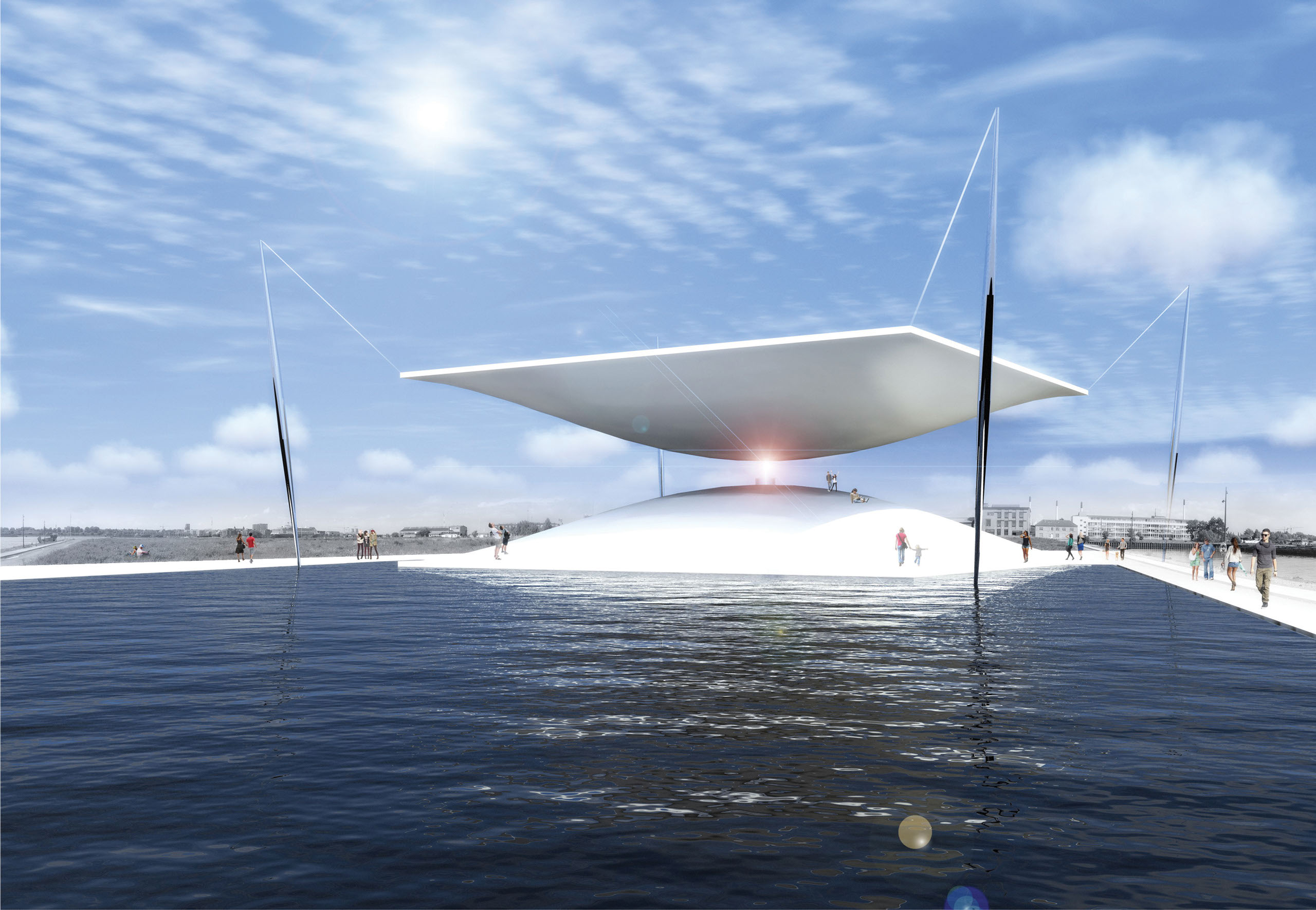

So far, they have held design competitions in Abu Dhabi, Copenhagen, New York, Santa Monica, and the most recent one is in Melbourne. Competition submissions, made by professional and student collaborations of engineers and artists, are split into different technologies, such as photovoltaic, windmill, solar thermal (which focus solar energy with mirrors to heat a fluid for a turbine, such as in the 'hour glass' concept in the lead image), and various newer technologies that capture energy from pressure, movement and ocean currents. They also require that the designs are technically feasible and will actually make a significant amount of electricity--the hour glass sculpture in the lead image, for example, is projected to power "about 1,000 homes, with a beautiful work of art," explained Ferry.

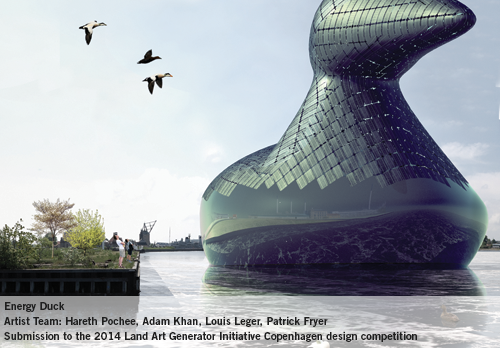

"Using polycrystalline solar panels, one team came up with the energy duck," said Ferry of a winning submission to their conference in Copenhagen (see photo below). "We saw yellow rubber ducks making appearances all over the world. This design can power 40 to 50 homes and it’s done with straight off-the-shelf panels on a frame--we're currently working to implement this."

Monoian and Ferry explained that they want to give environmental advocates something to get enthusiastic about when it comes to fighting CO2 emissions and climate change. "You can only take so many rising sea level predictions," said Ferry. "It’s so overwhelming it shuts people off to action. We want to give people something to run towards, rather than run from in the future."

In addition to the international competitions, the two do smaller, city-by-city projects, such as a six-week "Art and Energy Camp" they did in Pittsburgh for kids. "We showed kids a nuke plant and coal plants in Western Pennsylvania," explained Monoian. "And we got kids to help design and build a solar sculpture to feed into a community center." And while most of the designs are currently just renderings and concepts (although it sounds like many are well into development) the project in Pittsburgh was seen to fruition and now occupies a space that was previously a defunct billboard. The also put together an art mural project in San Antonio, Texas, by finding a firm that developed a paintable film that could go over solar panels. That way the city's murals, in addition to being beautiful, help produce electricity.

Moving forward, the two hope the designs will be used in cities across the world to enliven public spaces while they reduce CO2 emissions. "Art, such as public fountains are great," said Ferry, "But fountains use energy. Our designs can be beautiful while they make energy."

A few more examples of the designs and ideas below:

To see more proposals/power generation artwork, check out 2016's submissions portfolio.

For more events like these, visit SPUR’s events page.