Note: Metropolitan Shuttle, a leader in bus shuttle rentals, regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog Los Angeles. Unless noted in the story, Metropolitan Shuttle is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

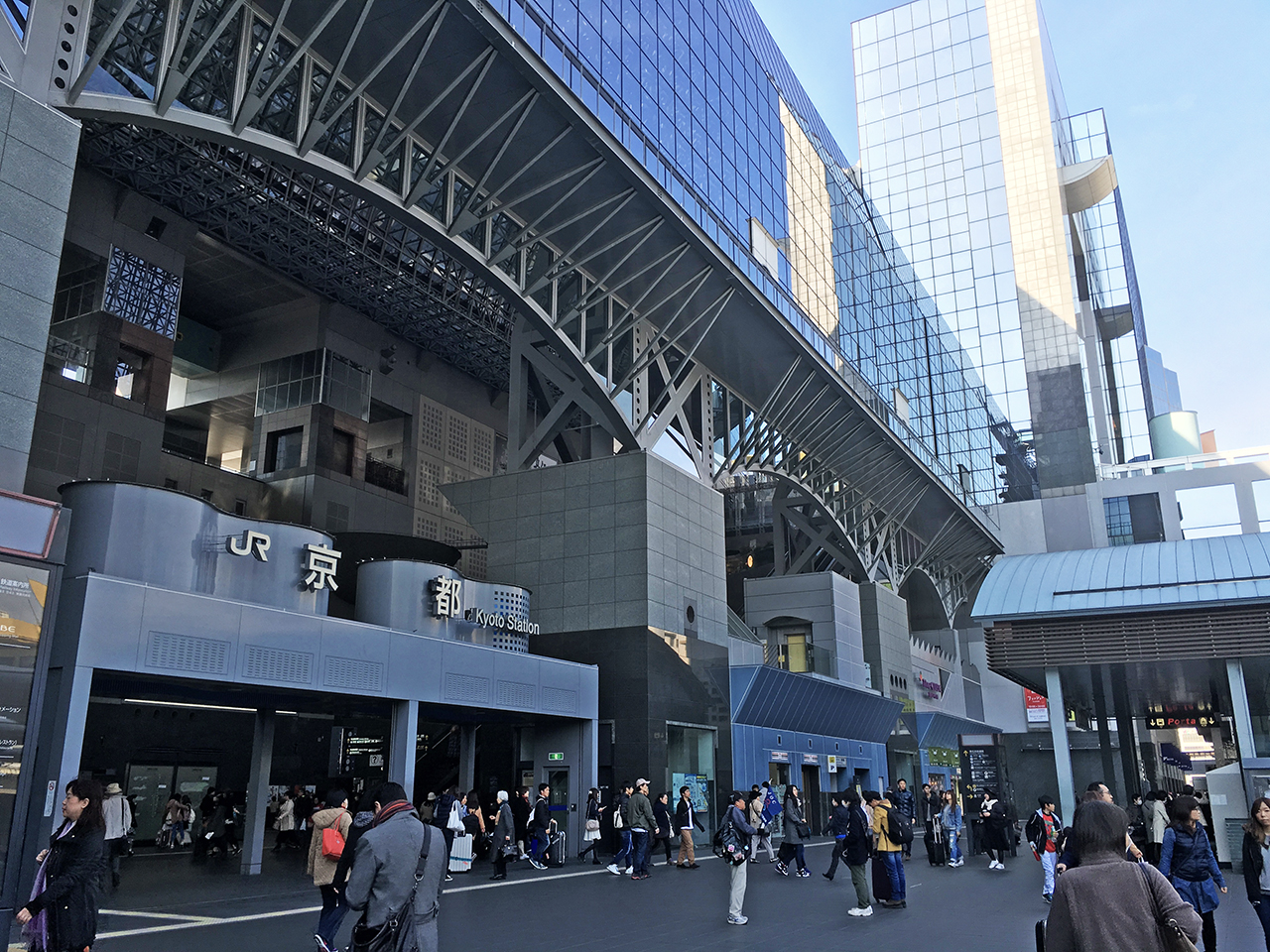

"Who has been to Kyoto Station in Japan?" asked Kate White with the California State Transportation Agency during a SPUR panel this afternoon about how to properly develop around the state's growing rail network. Kyoto Station, as seen in the lead image, is an incredible agglomeration of shops, department stores, and intense commercial development. The Japanese railway system, by encouraging such intense developments around hub stations, captures every last bit of value created by the presence of the rail lines. "We need development tools so you don’t just get off the train in California and there's nothing there but a platform...or a parking lot and a Costco."

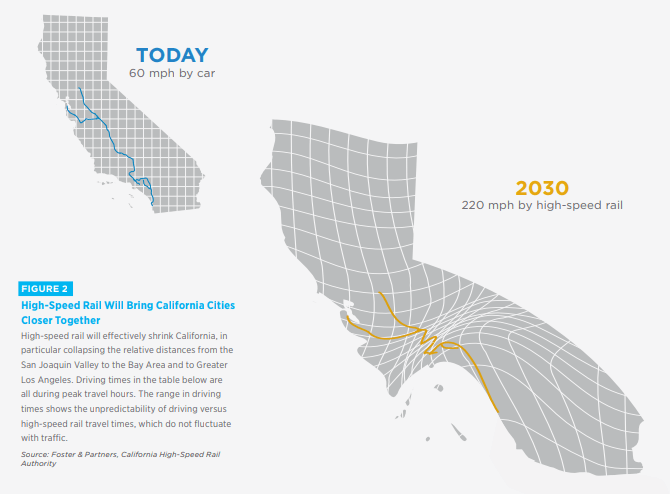

This is the challenge facing lawmakers and policy analysts as the state builds out its State Rail Plan, of which high-speed rail is the centerpiece. This is especially an issue in the Central Valley, in cities such as Fresno, Madera and Bakersfield, which will suddenly find themselves a short journey from Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Jose.

"We need to think differently about the Central Valley," said Egon Terplan, SPUR's Regional Planning Director, who hosted the panel. In Central Valley cities, there "...continues to be pressure for outward growth. Land is cheaper, so Bakersfield and Fresno haven’t seen as much infill as we’re starting to see in Southern California and Bay Area."

The cities of the Central Valley all have historic cores based on the train systems of old. And those cores stand to become very valuable real estate again, when they are a short train ride from San Francisco (see map above to get a sense of how distance and time will change). "A lot of them have a downtown core that got hollowed out in the freeway-building era," said Terplan. But with HSR coming, they have a chance to revitalize and grow their downtowns. That's going to require early work now, expanding street grids, improving sewers and other infrastructure, and just generally preparing for development.

But local and state laws make it hard to concentrate development around stations. That's not just a problem in the Central Valley of course.

Terplan cited North Berkeley BART as an example of how badly station-area development can go. "Think about the investment in underground rail, and four decades later we have no developments? The local community got the transit but there was no oversight to achieve the development."

If the state wants to achieve its goals of reducing car trips and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, there can't be any more North Berkeleys--certainly not on the high-speed rail system. For its part, SPUR developed its Harnessing High Speed Rail report, with guidelines for policies and approaches for financing and building good station areas. But good guidelines and plans are meaningless without financing, incentives, and sometimes mandates. "Rail operators need an explicit role in governing the districts and being able to value capture," said White.

That's why lawmakers such as San Francisco Assemblymember David Chiu are working on legislation to streamline development around stations. "We don’t need acres and acres of surface parking lots," said Judson True, Chiu's Chief of Staff.

He pointed out that even when station-area development is done well, it takes too long under current laws. "It’s taken 20 or 30 years to make the Fruitvale Station happen." Assembly Bill 2923, ("Bay Area Rapid Transit: Transit-Oriented Development Zoning Standards") co-authored by Chiu, would require BART to establish TOD criteria that local jurisdictions would have to follow. This is to avoid having local municipalities tie up projects because they demand nothing but parking at stations at the expense of housing and commercial development.

True explained that local officials who push against denser transit-oriented development mandates generally complain about the loss of local control (as they did with State Senator Scott Wiener's SB-827, which intended to override local density limits around transit). But with Chiu's bill they're not taking away local control--"we're shifting it to a different locally elected board, the BART Board."

The panelists suggested this might be the right approach for similar legislation intended to make sure development happens around HSR stations--in other words, let the regional transit agencies determine the criteria around the stations.

True said these bills are just the start of a conversation about getting more housing around rail stations. One audience member, however, pointed out that most recent development around the downtown Oakland stations and most of what is planned for West Oakland is commercial real estate. The reason: the lack of any more capacity on BARTs core system means there's no longer room to move more people from the East Bay to jobs in downtown San Francisco. The hope is that by focusing on building offices instead of housing in Oakland, BART trains can start carrying more people in the off-peak direction to jobs.

But that just speaks to the tight bond between good development and good transit. "Long term we need more Transbay capacity--and that's also part of our state rail plan," said White. True added that they want the tools to create both housing and commercial development around stations. He said that despite California's incredible growth, it's still saddled with "terrible land-use policy" left over from the age of automobile-oriented development. And that, of course, is what everyone on the panel, and in SPURs audience, are striving to fix.

For more information, check out SPUR's 'Harnessing High Speed Rail' Report.

For more events like these, visit SPUR’s events page.