A bill sailing through the Senate would give cities — and grassroots groups — a chance to heal urban neighborhoods by tearing down and repairing the damage done by 1960s-era highways.

The "Community Connect Grant" — a tiny program in the context of a new transportation bill that seeks to increase highway spending a whopping 40 percent — would provide $120 million over five years to reconnect neighborhoods that were torn apart by urban-renewal era highway projects. Often these projects specifically targeted low-income neighborhoods or black and brown neighborhoods for demolition and displacement.

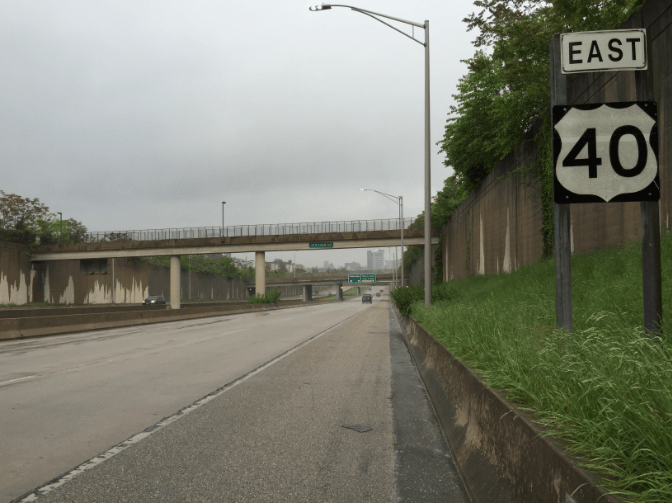

One example is Baltimore's Interstate 170 — aka "The Ditch." This 2.3-mile channelized highway bisecting West Baltimore is sometimes referred to as the "highway to nowhere." Originally designed to be part of the interstate system, connecting to I-70 and the Beltway, it became a useless isolated highway node when wealthy residents successfully blocked I-70's construction.

Now "The Ditch" carries so few vehicles a day, the city sometimes doesn't plow it. Still it serves as a major obstacles for the neighborhoods surrounding it.

"It’s a big scar on the urban fabric," said Jed Weeks, policy director for Baltimore's bike advocacy organization, Bikemore. "It just doesn’t feel good to walk around there because it’s just this sort of big empty ditch."

Both of Maryland Senators, Ben Cardin and Chris Van Hollen, were instrumental in helping introduce the "Community Connect Grant" as part of the transportation bill advancing through the Senate [PDF] in part to deal with problems like The Ditch.

Federal transport policy has come a long way over the last decade on highway teardowns. The Obama Administration funded a number of highway teardowns, including ones in New Haven and Rochester, through its TIGER program, another competitive grant program.

This program would further establish highway teardowns as a legitimate federal funding priority.

"It’s still a grant program, but I think it’s putting more money toward it and really calling it out as an issue," said Caron Whitaker, VP of government relations at the League of American Bicyclists.

The program would provide $2 million competitive grants technical assistance and planning. One cool aspect of it, said Ben Crowther at the Congress for New Urbanism, is it would allow non-profit organizations and community groups to apply for funding to get the ball rolling on plans. Often highway teardown projects are initiated by design-related groups like Tampa's Sunshine Citizens or Syracuse's Moving People Transportation.

In addition, it contains safeguards to help prevent cities or states from replacing highways with roads that are highway-like and unsafe — something we've seen emerge as a problem in these cases in cities like Seattle. It would also require the "inclusive economic development" for replacement, which hopefully, would help address concerns about gentrification.

Rochester's Inner Loop Highway — which has been partially filled in thanks to a $22-million project partially funded by a TIGER grant — is a great example of how dramatic a difference these kinds of projects can make.

This shows what it looks like in the final stages of (de)construction.

And here is just one development proposed for the six to eight acres of developable land that was created.