Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

Daniel Curtin, a California High-speed Rail Board Member from Sacramento, and Laura Friedman, an Assemblymember who represents Burbank and parts of Glendale and Los Angeles, led the charge at a recent hearing of the Assembly Transportation Committee to divert billions from California's High-speed Rail project to Metrolink, L.A.'s commuter rail system.

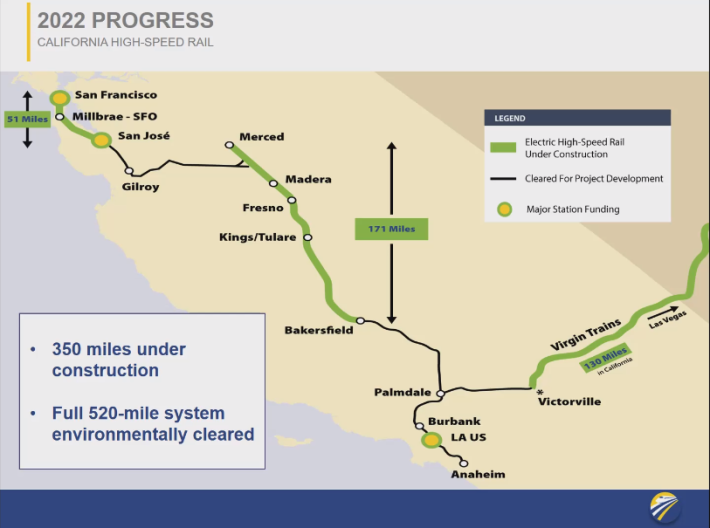

Currently, the California High Speed Rail Authority (CAHSRA) is constructing a 171-mile line from Bakersfield to Merced that will eventually become the spine of a statewide system, stretching from San Diego to San Francisco and Sacramento. In a couple of years, when that spine is completed, the strategy is to open an interim service where trains would run around 200 mph from Bakersfield to Merced, with connections to San Jose via the Altamont Corridor Express (ACE) commuter rail service (which is currently being extended to Merced in a separate project) and Oakland and Sacramento via Amtrak's existing San Joaquin service.

To achieve such high speeds between Bakersfield and Merced requires electrification--overhead wire to deliver the power a train needs to accelerate to 200 mph. Friedman and Curtin want to forgo the $4.8 billion cost of electrification and instead run Amtrak and ACE's existing diesel engines on the high speed corridor, since they could potentially reach a top speed of 125 mph on such perfectly straight tracks (although diesels have poor acceleration, so it would take a long time to reach that speed). Amtrak's trains currently top out around 80 mph in most parts of the state, primarily because of curves, track quality, and regulations that limit the speeds at which they can traverse grade crossings.

Curtin, Friedman, and other supporters of transferring investment to Southern California argue that whatever time savings might be made from having electrified 200 mph HSR on the Central Valley spine would be lost by forcing riders bound from Bakersfield and Fresno to the Bay Area to transfer from electric trains to Amtrak and ACE at Merced. "I don’t see how you get people off the train and back onto the other train, with their baggage and strollers," said Friedman at the hearing. "The one-seat ride is always the answer--always," added Curtin.

Brian Kelly, the High-speed Rail Authority's CEO, replied that he would like to see all rail projects funded in the state, rather than simply pulling funds from one project to another. Estimates say that an electrified HSR line will save about 100 minutes over Amtrak's current Bakersfield-Merced service. "Speed is of the essence, and when the spine system that does go fast connects into those regional areas...it will lift ridership on all of them."

Friedman and Curtin's argument, meanwhile, doesn't make much sense. If they're really interested in eliminating the transfer at Merced, then yes, they could have Amtrak's existing trains run to Bakersfield on new tracks. But there are also multiple ways to do the reverse: 200-mph, electric high-speed trains could continue at a slower pace from Merced, running directly to San Jose, Oakland, and Sacramento on existing tracks.

For example, in France TGV high-speed services slow down and continue from electrified, 200-mph lines onto old, non-electrified lines to offer one-seat rides from Paris to rural villages, such as Les Sables-d'Olonne, a seaside town in Western France. At the end of the high-speed line, they connect a diesel locomotive to the front of the train (this takes about ten minutes) and it continues on its way at a lower speed, as seen below:

So it's a one-seat ride; the train itself does the transferring. Another option is to use something such as the RENFE dual-mode HSR sets from Spain, which can run on diesel or electric with no need to change locomotives (albeit the top speed of this particular train in electric mode is only 160 mph).

But, as officials close to the project opined to Streetsblog, Friedman and others aren't truly interested in eliminating transfers. They just want more money for their home districts (Streetsblog has calls and emails in to Friedman and Curtin and will update accordingly).

Kelly is right: it's time to stop fighting over what gets built first. Lawmakers need to put parochial interests aside and work to modernize the rail network, not just in the Central Valley, the Bay Area, or Los Angeles, but all across California.