SPUR Talk: Rules for Successful Mega Projects

4:23 PM PDT on April 1, 2020

A look at the basement of Transbay, waiting for its trains. Photo: Streetsblog/Rudick

The Caltrain connection to the Salesforce Transit Center. The Central Subway. The Eastern Span of the Oakland Bay Bridge. There's no shortage of problematic, multi-billion-dollar mega projects in the Bay Area. Some get completed, despite costs soaring. Others are way behind schedule. Some turn into ghost projects--with planning and design in various stages of completion, but huge delays and no real work underway. "Why do projects fail? It usually isn’t technical or financial reasons," explained John Porcari of WSP during a SPUR webinar on improving project delivery in the Bay Area. "The most common cause of death is a loss of political support. It can happen in a lot of ways, but the root causes are built in at the beginning of the project."

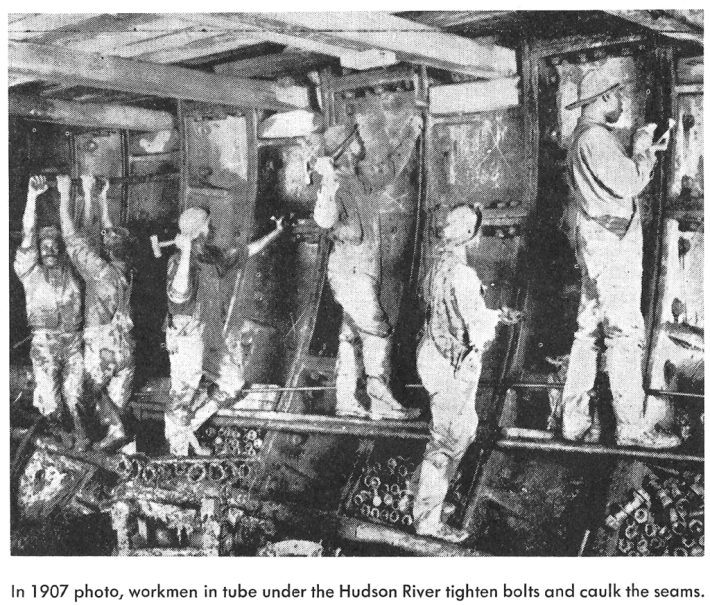

Porcari said that often comes up when projects cross political boundaries. He gave the example of the Columbia River Crossing, "...connecting the state of Washington and Oregon." The project fell apart because of political changes. "We needed two governors and two legislatures to stay in sync and ultimately we lost one of the legislatures." The other example he gave was the Access to the Region's Core or "ARC Tunnel" rail project between New Jersey and New York. As he explained, all heavy rail service between Boston and Washington DC currently depends on one two-track tunnel under the Hudson River between Manhattan and New Jersey. The tunnel, however, was opened when the HMS Titanic was still under construction. "That tunnel needs to be replaced, but to make the case we had to build a value proposition."

That didn't happen. Instead, the project was viewed as something to help New Jersey commuters get to midtown Manhattan. And when governor Chris Christie of New Jersey came into power, he decided it was too expensive and he killed it. "We learned early building of a regional consensus for a project of that magnitude is essential," said Porcari.

Years were lost. But the project was eventually reborn as the Gateway project. Since the existing, 100-plus-year-old Hudson River tubes are the only way for trains to get between all points on the Northeast Corridor, it is now framed as a much larger project, significant to the entire country. "It is a single point of failure for 10 percent of America's GDP. It’s a single point of failure between Boston and DC," said Porcari. "There is no other way for passengers on Amtrak to get to and through the New York area. That value proposition has been compelling enough to build support in Connecticut, NJ, and NY for the project." And really the whole country, he explained.

He also explained that while a project needs specific political champions, it also needs clear community support so that the next batch of politicians will continue to give it support as the project grinds on. "The Purple Line is a 16-mile light-rail project in the state of Maryland, that is circumferential to DC, and connects four metro lines, commuter lines and Amtrak," he said as an example (see map below). The project leaders got the local communities all along the line on board, selling its value to serve "...transit deserts in communities that had no or little service before." It also incorporated a 'brownfield' project to restore areas along the lines and keep residents--and the politicians who represent them--steadily behind the project.

Still, large projects can be a series of stops and starts. "Projects usually have near-death experiences," added Porcari. "You have to get around or over or through those experiences."

The Bay Area, of course, has its own projects that have stopped and started but are essential to improving transit in the Bay Area. There's the downtown rail extension that would bring Caltrain and high-speed rail into the basement of the Salesforce Transit Center (see the lead image of the Transit Center's train station without any trains). There's also the need for a second Transbay crossing. Both have been in various stages of design, advocacy, and discussion for decades.

"How can we deliver the next generation of transit project more quickly and less expensively?" asked Laura Tolkoff, director of SPUR's Regional Strategy initiative, who also presented at the webinar. "We’re going to have to do more with less... we need to build transit projects that we need to shift to a more sustainable future."

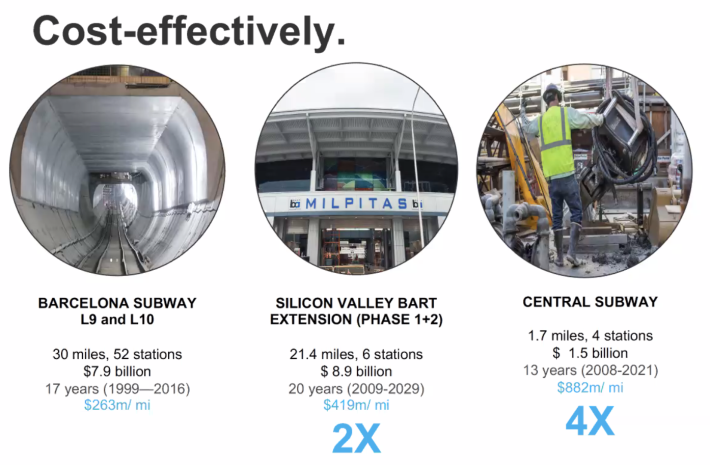

Tolkoff suggested that with the country sliding into a recession because of the COVID-19 pandemic, it's important to double-down and build the economy back up over time through important projects. However, business as usual won't suffice. She used the San Jose BART extension and the Central Subway as examples. "It's taking 30 to 50 years to complete" big projects, she said, adding that compared to other countries, the Bay Area is spending two to four times "..as much money for projects that are less complex" (see diagram below).

And then even when they get completed, political conflict results in inferior projects. "We build projects that aren’t delivering on their promises." She gave the example of the Marin-Sonoma SMART train, which finally completed a long-delayed extension to connect it with the Larkspur ferry to San Francisco--except it didn't quite make it. "Unfortunately, it’s still a very unpleasant and long 12 to 15 minute walk to get there [from the train station to the ferry terminal]. A lot of that came down to local opposition to views being blocked," she explained.

So in addition to Porcari's recommendations, what has to be done so Bay Area transit projects are built better, faster and more cheaply? A big problem, said Tolkoff, is the piecemeal way projects are funded. "Over 50 percent of budgets come from ballot measures," she explained. An example is High-speed Rail, which was put on the ballot in 2008, but in the form of a $9.95 billion bond issue that was just for a down payment on a much larger, more expensive project. Without a dedicated funding stream at the start to bring the project to completion, it was impossible to calculate the true timeline and costs. "Because of the failure to prioritize and fully fund important projects, it adds delays and costs, so we have a peanut butter, spread-it-around approach to costs that keeps projects half alive," she said. The delays and the fight to get funding at the Federal level then hurts political support.

The other problem is litigation. "The misuse of the environmental process adds delay... the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) is misused to stop or delay projects," by five to ten years she explained.

To start trying to fix this, she explained that the Bay Area needs to build on the Seamless Bay Area idea--start planning projects by looking at the regional transportation systems as a single network and then figure out what will get transit riders the most bang for the buck. Right now, each of the region's 27 transit agencies looks through its own lens and planning of big projects reflects that. "Develop a long term strategic plan for the regional network to drive planning," rather than having each agency submit to the Metropolitan Transportation Commission for funding. "We struggle more with 'is this a San Francisco project? Is this a San Jose project?' What we really need is to say is 'this is a plan that’s significant to the region or state’s transportation network.'"

The state also needs to remove regulatory hurdles. "Certain projects should be exempt from CEQA by statute," she explained, giving Bus Rapid Transit on existing lanes and bikeways as examples of exempted projects since they clearly don't cause significant environmental problems. "We need statutory exemptions to create more predictable budgets."

Tolkoff suggests the establishment of an "Infrastructure Bay Area" organization to plan, prioritize and approve projects for the whole region, and--one hopes--override parochial interests. Although she's reluctant for the Bay Area to create yet another agency, she thinks it's necessary to have a specialized, project planning and delivery authority modeled more on "Infrastructure Ontario" in Canada or "Network Rail" in the U.K., than the Bay Area's MTC. This new body would be staffed with people who know Porcari's rules--and are dedicated to getting projects done.

SPUR is coming out with a white paper shortly about how that agency would work to improve things over current planning and funding structures.

To see a recording of the full presentation, click here.

For more events like these, visit SPUR’s events page.

Read More:

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Streetsblog San Francisco

Commentary: Making Valencia Better for Business

Curbside protected bike lanes with curbside parklets deliver on much-needed economic benefits for merchants while ensuring safety for all