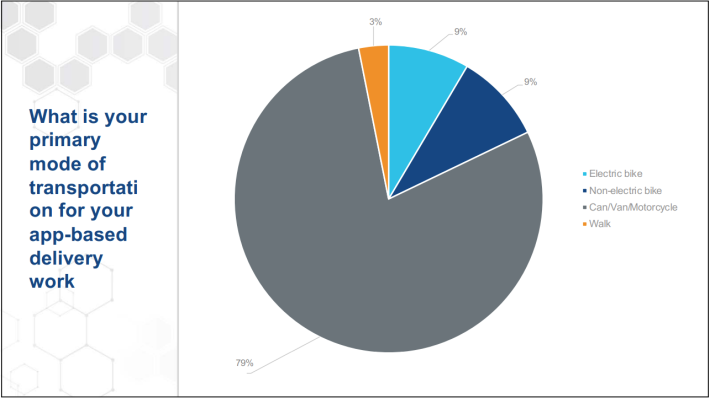

Nearly twenty percent of delivery workers in San Francisco use bicycles as their primary means of getting around, according to a new study commissioned by the Local Agency Formation Commission of San Francisco, which does policy studies for the city.

Although the study was looking at ways to protect all delivery workers, it called out the importance of considering the additional safety and health needs of those who do deliveries on two wheels (or their feet). "I wanted to get a really good snapshot of this workforce to inform city policy decisions," said Bryan Goebel, executive officer of the commission (and former editor of Streetsblog San Francisco).

"This is an incredibly vulnerable workforce, and many were just on the edge before the coronavirus crisis," said lead researcher Chris Benner, a professor of environmental studies and sociology and the director of the Institute for Social Transformation at UC Santa Cruz, where this the survey of app-based delivery workers was designed. "The crisis has put them over the edge. Because of their employment status, they fall through a lot of cracks in the relief packages that have been approved by the state and federal governments."

The results were presented to the full commission during an online meeting this morning.

"No one else has done a survey like this," said Goebel, who has also worked for Uber Eats, during this morning's presentation to city officials. "Folks forget people also do it by bike, walking, hover-board, stand-up scooters. That does get lost sometimes."

From a release about the study:

The unique, in-person survey reached 643 workers with Uber, Lyft, Doordash, GrubHub, Instacart, and Shipt early this year. When the shelter-in-place order took effect, researchers developed an additional two-week, online survey to capture the effects of the pandemic on app-based workers—a growing population that enjoys little job security and few employment rights.

And:

The baseline survey reveals a workforce that is 56 percent immigrant, mostly male, and that struggles to make ends meet, with many relying on public assistance despite working an average of forty hours per week. Since the pandemic, the online survey revealed, more than half have lost 75-100 percent of their income.

This hammers home the intention behind AB-5, which aims to force companies to provide benefits to so-called "gig workers." The study authors stressed that a new economy has been created in which workers receive no benefits nor the basic safety protections that conventional, 'full-time' employees get. This means no breaks, bathroom facilities, healthcare, etc. And in the time of COVID-19, it also means no protective gear for workers who are taking enormous risks delivering food and other supplies to people lucky enough to be able to shelter in place.

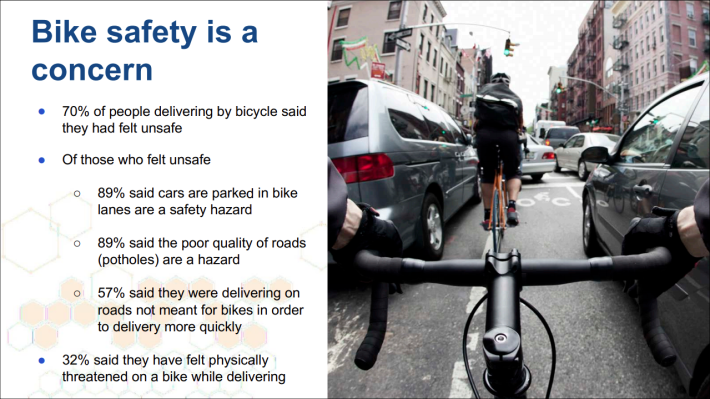

Some of that is regulated at the state level. But for app-based workers (as they might be more accurately called) on bikes, there's of course yet another element to the hazards they face--and one which the city itself can fix--and that's unsafe streets.

Seventy-seven percent of delivery workers who participated in the study said they prefer delivering by bike or walking because it was less stressful and a good source of exercise. More than eighty percent also think it is quicker to deliver using a bike than a car. And, of course, it's cheaper to buy and maintain a bike than a car.

But many are deterred from using a bike for the same reasons the public in general is: seventy percent of people delivering by bicycle said they have felt unsafe. The solution is a familiar one to Streetsblog readers: "We think the SFMTA should do a rapid build-out of protected bikeways,” said Goebel during today's presentation. "Especially on busy streets."

He added that the city needs more loading zones on busy corridors, to reduce interactions between cars and bikes. He also told the commission that the city should expand the 'slow streets' program and make it permanent. "Not only does it help everybody to get out and exercise, but bike delivery people can use these streets,” he said. This would in turn help encourage more delivery drivers to use bikes (and e-bikes) and get more cars off the road.

More from the study:

The baseline survey, which reached 407 ride-hailing workers and 236 food-delivery workers, revealed a workforce on the margins:

- 21 percent of participants have no health insurance, and another 30 percent depend on public insurance sources, such as Covered California or Medi-Cal

- 15 percent receive some form of public assistance, including 13 percent of food-delivery workers who depend on food stamps

- 45 percent report they could not handle a $400 emergency expense without borrowing money

Half the participants report working forty or more hours per week in app-based work, and nearly 40 percent have worked more than two years for their "survey app"—the app they were working on when recruited for the survey.

"This is not a 'gig.' This is full-time work for the majority of these workers," said Benner. "More than one-third are supporting children and nearly half are supporting other adults."

More info on the study below: