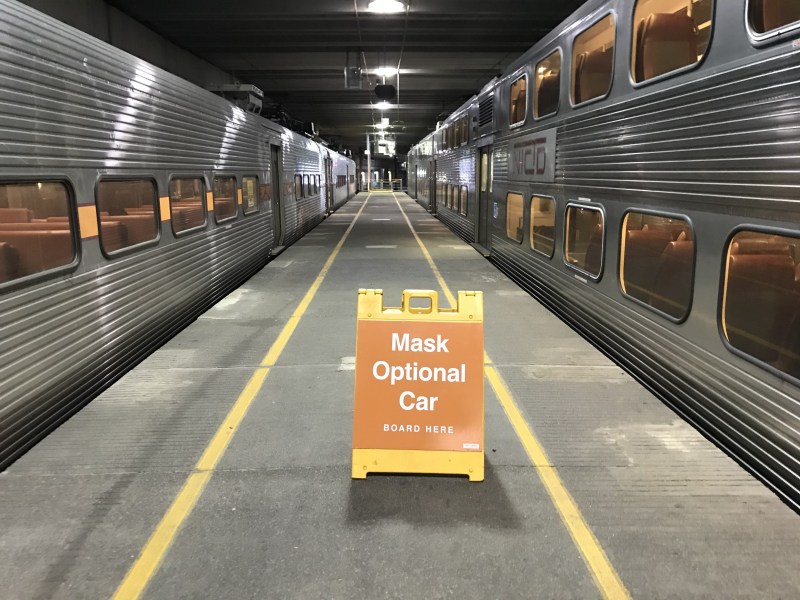

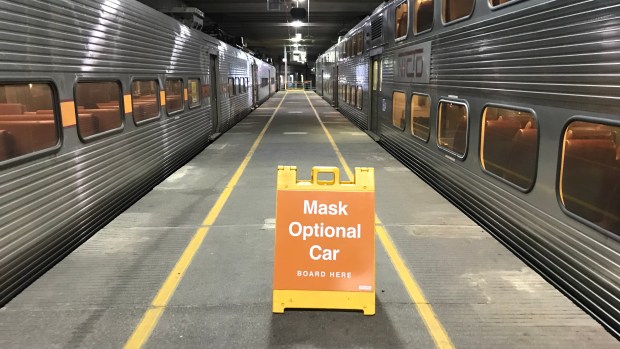

On Friday when I rolled my bicycle onto the South Shore Line commuter railroad platform in Chicago’s downtown Millennium Station to embark on train-plus-bike camping trip to lovely Indiana Dunes National Park, I was shocked to see a sandwich board on the platform identifying the last rail carriage as the “Mask Optional Car.” The line heads as far east as South Bend.

After all, pandemic experts say that masks are an effective way to block respiratory droplets and prevent COVID-19 transmission, and since April 30 an Illinois executive order has required the use of masks or face coverings in all indoor public spaces, including transit. The other three transit systems that serve the Chicago region — the CTA, Metra commuter rail, and the Pace suburban bus system — all currently require all passengers to wear facial coverings at all times.

Indiana, which, unlike Illinois, went for Trump in the 2016 election and has had a somewhat lower coronavirus mortality rate than the Land of Lincoln, was slower to act, but issued a face covering mandate on July 27.

Worse, the designated COVID-denial friendly South Shore car was also the only car on the train with bike racks. Almost all of the passengers on board were mask-less. Disgusted, I parked my camping gear-loaded bike in a rack, locked the front wheel to the frame, and retreated to the next car, peeking though the door glass from time to time to keep an eye on my cycle. But it seemed pretty ironic that bike riders, people who are probably more likely than the general population to be health-conscious, were being encouraged to share an enclosed space and breath the same air as folks who are refusing to follow public health protocols.

When I tweeted a photo of the Mask Optional Car’s sandwich board, there was a nearly universal reaction of disbelief and horror from transit advocates. No one was aware of any other U.S. rail systems that are accommodating anti-maskers this way.

A July 27 announcement on the South Shore Line website, correlating with the issuance of Indiana’s mask order, stated “Except within the ‘Mask Optional’ car located as the second car of every train, masks are required to be worn by all passengers unless excused for reasons of deafness or medical conditions.” Presumably the exception made for deafness is because if you’re hearing impaired and your companion is masked, you may not be able to read their lips (although clear medical masks do exist.)

Oddly, the South Shore announcement noted that Indiana’s St. Joseph, Laporte, and Lake Counties were requiring facial coverings in public areas (perhaps the announcement didn’t factor in the statewide order issued that day?) and stated, “Passengers seated in the Mask Optional Car are requested to govern their behavior consistent with the mask requirements posted by those counties. Seeing as how only one Hoosier State county the train runs through, Porter County (home of the Indiana Dunes), didn’t require masks, was the railroad suggesting that COVID deniers in the corona car wear masks for most of the ride, but take them off when passing through Porter County? It made no sense.

Wtf are you doing @southshoreline? Why is this ok @GovHolcomb? Is this car allowed into Illinois/Chicago? Bc that doesn’t sound like it works w/@GovPritzker or @chicagosmayor’s edicts https://t.co/npiKnZn2cf

— SM (@ims714m) September 23, 2020

The day after I reached out to the South Shore Line for more info on this baffling policy, Mike Noland, president of the Northern Indiana Commuter Transportation District, which runs the railroad, gave me a call. Noland insisted that NICTD strongly believes in the importance of wearing masks on transit during the pandemic, and said conductors have a supply of spare masks to offer to passengers who lack facial coverings. “But as you know, there are people here who feel it’s their God-given right not to wear masks — they think it’s a government conspiracy.”

While the South Shore Line previously required masks in all cars, “If [riders] don’t want to comply, there’s not a whole lot we can do,” Noland insisted. “If [elected officials] give us a law we can enforce, we’ll pivot.”

While it’s clear that Illinois, Indiana, and most of the local county guidelines do require masks on transit, Noland argued, “We’re sort of in Limbo,” noting that if a maskless passenger refused to leave the train, “I would have to stand behind arrest charges.”

He’s got a point that enforcing mask laws could be problematic. Removing COVID deniers from transit would likely require police involvement, which could easily escalate to violence. In February, on the very day that Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot announced a law-and-order crackdown on the CTA, police shot and critically injured a man while trying to detain him for the minor offense of illegally walking between rail cars.

Therefore a zero-tolerance mask enforcement policy towards masks on transit could arguably be counterproductive to public safety. As such, the CTA, Pace, and Metra are not actually refusing service to non-masked riders, which has resulted in imperfect compliance and a backlash from concerned transit employees and passengers. Chicago’s Active Transportation Alliance has argued that “carrot” incentives such as installing free mask dispensers on all buses and trains is a better approach than punitive “sticks.” ATA didn’t respond to a request for comment on the South Shore policy.

Metra spokesman Michael Gillis indicated the commuter railroad, which has a similar style of operations as the South Shore Line, including onboard conductors, is using a soft-touch approach to mask compliance. “Our conductors are expected to make regular announcements over the PA regarding the need to wear a face covering or mask for the duration of their trip,” he said. “They are also expected to make a similar announcement as the enter each car to validate fares. And just this week, we started supplying our conductors with individually wrapped masks and instructing them to approach any customers who are not wearing a mask and politely ask if they would like one.”

Gillis said the railroad is not removing people from the trains for not wearing masks or face coverings. In contrast, during non-pandemic times, it’s common for the conductors to kick fare evaders and others who violate Metra rules off of trains, sometimes calling police for backup.

The South Shore Line’s Noland argued that the Mask Optional Car policy has been a win in terms of mask compliance in the other rail carriages, and customers’ safety and comfort. (He said that the no-mask car is never supposed to be the same one as the bike car, and promised that NICTD’s chief operating officer is taking steps to ensure that mistake doesn’t happen again.)

“We had complaints [about mask non-compliance in the regular cars] before implementing this policy, but we’ve had zero issues since we put this in place,” Noland said. “We have 100-percent perfect compliance in the other cars nowadays. A lot of people have told us they find it reassuring to ride in a car where everyone is wearing masks.” Interestingly, he said that the railroad had received “not one bit” of pushback about coddling COVID deniers until I started publicizing the issue on Twitter.

Noland did say that, in the event that a coronavirus flat-earther refuses to move to the Mask Optional Car when asked, he’s prepared to have them booted from the train. “I had discussions with our team and with our legal counsel that we’ll be enforcing this requirement.”

The South Shore Line president argued that, rather than making the railroad a national laughingstock, the Mask Optional Car policy may wind up being considered a best practice by peer rail systems. “Frankly, I’ve gotten a lot of feedback from other transit agencies saying, ‘What a great policy; I wish we could do it.’ I’ll admit it’s not a perfect system, but our approach is working.”

It’s certainly an interesting concept, the idea that segregating passengers who aren’t taking the pandemic seriously helps protect riders who are doing the right thing. On the other hand, it’s possible that concentrating all of these COVID deniers in one place, sort of like an indoor, mask-less Trump rally, makes it more likely they’ll infect each other, and then later pass along the disease to innocent bystanders.

At any rate, it will be interesting to see if the South Shore Line’s unique approach will remain in place once it becomes widely known (I’ve already heard from another news outlet that’s planning to report on it), and possibly faces legal challenges.