This article first appeared in the Frisc and is reprinted with permission.

Last September, on the day San Francisco’s skies burned orange and blocked out the sun, a top candidate for District 1 supervisor, Connie Chan, tweeted a photo of herself holding a signed copy of the Sunrise Movement’s Green New Deal pledge. In the tweet she called the day an “alarming reminder of the reality of climate crisis” and pledged to put “the health of our families, climate, and democracy over fossil fuel industry profits.”

Two months later, Chan squeaked out the narrowest of victories — with the Sunrise Movement’s endorsement. (“Chan’s climate goals closely align with Sunrise’s GND goals.”) But now, she’s got her fingerprints all over a plan that seems like a high-speed U-turn.

For months, Chan has been voicing her support for reopening the Great Highway, which had been closed to cars since last April as part of the city’s emergency pandemic response. That support bolstered Mayor London Breed’s decision to reopen the beachfront road to cars on weekdays, drawing not only the ire of environmental, bicycle, and pedestrian groups, but also going against the wishes of a majority of San Franciscans surveyed in a March poll.

Megan Nguyen, a hub coordinator at the Bay Area chapter of the Sunrise Movement, said the move spoke louder than any campaign talking point. “Seeing them consistently compromise and choose cars over communities, choose convenience over resilience, it’s very disappointing, and I’m calling on our leaders to step up or step aside and let someone else take action,” Nguyen said. (In an earlier conversation, she noted she was speaking for herself and not the Sunrise Movement. Later, Nguyen confirmed that she is indeed speaking for Sunrise Bay Area, and also that the chapter “is firm in being disappointed and upset” at Chan. However, “amends can be made” if the supervisor reevaluates her decisions. As things stand now, though, Sunrise Bay Area won’t be supporting Chan.)

“Our hub will not support candidates who make excuses or compromises when it comes to our future and addressing the crisis,” she added.

Chan’s not the only SF official to talk big about the climate crisis. Only one month ago, ambitious legislation to update the city’s environmental code, sponsored by Breed, passed at the Board of Supervisors. Sup. Gordon Mar, who represents the Sunset district and was a partner in reopening the Great Highway, said last month that “we are in a climate emergency that will only get worse … We can go big and we can go bold and, frankly, we can’t afford not to.” (He was talking about his support for phasing out gas-burning appliances.)

Sup. Myrna Melgar, SF’s other west side supervisor who backed the Great Highway reopening, wrote that she would “continue to make climate resilience a priority” in a statement she issued following the mayor’s announcement.

As if any exclamation point were needed, the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report came out — and confirmed that there is no way to stop global warming from getting worse over the next 30 years — just four days after the surprise announcement.

Meanwhile, on the third day that cars were back, zooming up and down the Great Highway, the sun rose red due to wildfire smoke.

Shoreline showdown

Other pandemic street changes made permanent have been contentious, but nothing like the Great Highway. Proponents include climate, bicycle, and pedestrian activists as well as plenty of neighbors who don’t want to relinquish the flat two-mile stretch of car-free recreational space — the “Great Walkway,” as some dubbed it — that welcomed an average of 144,000 people a month during full closure, according to the Recreation and Parks Department.

Further south, the final stretch of the Great Highway will be permanently closed due to erosion by 2023, with plans to replace it with a path for cyclists and pedestrians. Higher sea level from climate change will make closure of the currently contested stretch inevitable too, say activists. “It’s just one parkway, but having it open to people and closed to cars can have such a larger impact,” Nguyen said.

Daniel Tahara, a software engineer who serves on the steering committee of advocacy network the Climate Emergency Coalition, cites research showing that people who live near highways often suffer adverse health effects from tailpipe emissions.

On the other side of the argument is the Open the Great Highway organization, which raises concerns about west side traffic impacts as adults return to work and children to school. (The reopening was explicitly timed for the first day of in-person learning for public schools.) They make a climate argument too, sort of: Stop-and-go trips on alternate streets burn more fuel than a smooth ride down the Great Highway, even with its traffic lights.

Yes, stop-and-go burns more fuel than highway driving, Tahara acknowledged. But by that logic, we should turn all our streets into freeways. Instead, Tahara said that San Francisco needs to be more consistent with its long-standing goals: reducing traffic violence and being a transit-first city (a policy about as old as my dad).

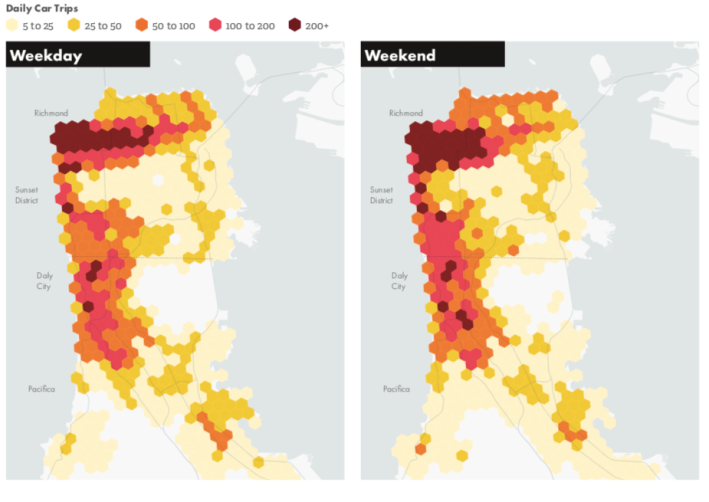

Before diving into data, it’s important to know that this stretch of the Great Highway has no neighborhood access. It is essentially a two-mile freeway that bypasses the Outer Sunset. Before COVID, in 2019, there were an average of 17,200 car trips per day on weekdays; 19,000 on weekends, according to SFMTA data.

About two-thirds of those trips started or ended in the Richmond district, north of Golden Gate Park. (This is why Chan has been involved; she represents the Richmond.) Most of the rest started or ended in San Mateo County. This traffic was not and will never be people going a few blocks to the grocery store.

Who’s behind the wheel

There’s no evidence yet that a permanent Great Highway closure would boost traffic and emissions across the Outer Sunset.

Here’s what we know so far. During the pandemic closure, west side car trips increased noticeably in a few spots, like the Chain of Lakes Drive through Golden Gate Park that connects the Richmond and Sunset districts. Planners have already made some street-level changes to address concerns, like keeping drivers from diverting en masse to the Lower Great Highway and other parallel streets.

But traffic also decreased dramatically on 19th Avenue and Sunset Boulevard, the thoroughfares expected to pick up most of the slack.

The “return to school” reason for reopening also raises questions, considering most Sunset district schools are in the middle of the Sunset, not easily accessible via the Great Highway.

Will a post-pandemic return to work also mean a return to previous traffic patterns? And could problems caused by the Great Highway closure be addressed through street-level changes? City planners wanted to find out by keeping the Great Highway closed longer.

In a June meeting, SFMTA planning director Sarah Jones said the agency “would get the best understanding of how this works with a full-time closure” extending beyond the COVID emergency. A majority of SFMTA board members and Rec and Park commissioners agreed and supported a car-free pilot study. That’s now on hold with the reopening. The Board of Supervisors could approve such a pilot later this year, but there’s no guarantee.

Until then, it remains unclear what the effect of a post-pandemic 24/7 closure would be on traffic and emissions.

What’s clear, however, is that cars have returned. The first day of reopening, The Frisc counted 409 in a 30-minute span during the evening peak. We went back three more times that week. We counted 488 in another peak evening session, and 504 and 688 cars in two morning peak sessions, all lasting a half hour.

It’s a tiny sample size, but consider this: In 2019 SF transit officials counted nearly 3,000 cars in three peak morning hours and nearly 4,000 in three peak evening hours. We can’t say that our reopening count would equal those numbers stretched over three hours, but we can say that plenty of drivers were ready to roll.

In a statement to The Frisc, Breed spokesperson Andy Lynch described the reopening as a compromise, and said it’s “important to look at the totality of the changes that have taken place in San Francisco in terms of pedestrian access to public space.” He highlighted Breed’s support for other green initiatives, like creating dozens of neighborhood street closures and thousands of restaurant parklets that crowd out parking spaces.

Mar did not respond to multiple requests for comment. An aide to Chan said she was on recess and not available to comment.

Shifting political sands

The fight has also opened a window into the political tensions and factionalism in San Francisco, where “people philosophically agree on most issues, probably 70 percent,” according to University of San Francisco political science professor James Lance Taylor. “But the politics of San Francisco is focused around the margins, and that 30 percent is usually fought around space, usage, and zoning.”

Like the sandy median that runs down its middle, the Great Highway has divided people of basically the same political identity. Chan and Mar’s progressive allies on the board, supervisors Matt Haney and Dean Preston, have rallied against reopening and aligned with moderate state Senator Scott Weiner, who represents SF in Sacramento.

Because supervisors are elected district by district, they can be highly attuned to the power of small neighborhood activist groups — power that Taylor said is unique to San Francisco.

Not far from the late Great Walkway’s northern terminus is a 1.5-mile section of JFK Drive, Golden Gate Park’s main drag, that has also been closed to cars since last April. It remains car-free, but the abrupt end of the Great Walkway (and, earlier this year, car-free Twin Peaks) has activists worried that JFK may be next.

Chan said two weeks ago that she would soon introduce a compromise resolution: Reopen a small stretch so that cars, which already have access to the park’s underground parking garage, can use surface streets to reach the museums from the north side, all while keeping the rest of JFK permanently car-free. This comes despite her comment in June that the Great Highway closure shouldn’t “push traffic into Golden Gate Park, particularly where residents are enjoying the road closures and slow streets.”

Like Taylor, Tahara says these space struggles illuminate the city’s workings. But for him, it’s less about progressive infighting than the difficulty in making hard choices.

“San Francisco has kind of chewed through the low-hanging fruit in terms of emissions reduction,” Tahara said, noting that SF’s electricity sources are now nearly emissions-free, its zero-waste programs are robust, and it’s the largest U.S. city to pass a ban on natural gas in all new construction, not including restaurants.

But when it comes to reaching the prize apples on higher branches — like cutting emissions from cars — “deciding how to use things like the Great Highway is among the few tools at our disposal,” Tahara added. “Not using them is putting ourselves in an even worse bind.”

***

Max Harrison-Caldwell is a freelance journalist.