Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

At 66th Avenue, west of Interstate 880, at the terminus of the Bay Trail's Zhone Way in Oakland, there's an art installation and a small park called the '66th Avenue Gateway' project. It's a beautiful spot with a grand sculpture, but good luck trying to get there from the neighborhood, less than a mile away, near the Coliseum BART station. "This is why the Coliseum is a failure," said Robert Raburn, a BART director and cycling advocate who helped guide yesterday's "Flatland Neighborhoods Ride" of Oakland. Sponsored by Walk Oakland Bike Oakland, the 17.5-mile ride around the city, which was attended by some twenty people, was a voyage through the history of infrastructure and how it ties into ongoing disparities.

Getting from the nearby neighborhood to this waterfront park by foot or bike requires navigating a giant freeway overpass/ramp complex with a narrow sidewalk and no bike lanes; 880 creates an effective barrier between the water and the community that is typical in Oakland. "We floated an idea of putting in K-rail or something on the overpass to create a place for pedestrians and bikes," said Raburn, but to no avail.

The stop at the Bay Trail park was near the end of the three-hour ride, which started at Rockridge BART. The ride was an educational tour of the pavement and infrastructure conditions in wealthier, well-connected (and historically white) neighborhoods versus the neighborhoods of East and West Oakland. Tom Holub, a planner with BikeLab, narrated most of the ride. "Cycling is a great way to get a feel for the city. And everywhere we go will be affected by the infrastructure."

Holub talked about how freeways, the elevated BART tracks, and other large infrastructure projects divided communities. "We'll discuss how decisions got made on infrastructure, and then hold in your minds... why has cycling and infrastructure and complete streets become identified with gentrification?"

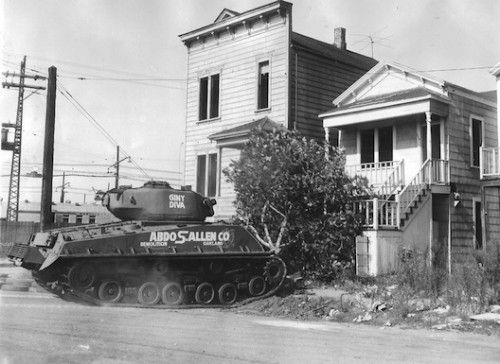

On the way from Rockridge to Martin Luther King Jr. Way, the ride stopped in front of the elevated structure of the BART tracks that creates the first divide between Rockridge and points west. Holub explained how the Black Panther movement viewed black communities as a colonized nation within the U.S., almost like Algeria was occupied by France. The way the BART line and the freeway system was built through African-American communities reinforced that view. "The freeways and the BART project demolished housing. Like an occupying force, they literally destroyed houses by ramming through them with a surplus army tank," he explained.

Before the freeway building age, West Oakland was actually the gateway for the entire Bay Area to the rest of the world. At Oakland's main train station, seen below, passengers coming from as far away as Chicago would transfer to ferries or take Key-system trains (Oakland's historic rail transit system) directly across the Bay Bridge to San Francisco. "This station had a forty-foot ceiling--it wasn't like the little whistle-stops we have today in Emeryville and Jack London," said Raburn. "This was a first-class station." Unfortunately, I-880 now makes it impossible to connect the station with any of the Bay Area's rail lines and, of course, the Key car trains were removed from the Bay Bridge in 1958.

"This was the center of the East Bay," said Holub. Not only did trains connect across the Bay, but the Key and Southern Pacific streetcar systems went all over Berkeley, Oakland and beyond. But then, of course, those systems were destroyed. "We started to build freeways that hemmed in the community." That hemming-in continues to cost and stratify Oakland. It's clearly evidenced by the quality of the street itself. In Rockridge, streets are lined with trees and the pavement is in relatively good condition. In West Oakland, the pavement is in terrible condition (as seen below). "The neighborhoods suffer from de-investment; the streets are un-rideable," said Holub.

The riders then continued on to the edge of I-980, which splits downtown Oakland from West Oakland. "This is three blocks from City Hall," said Holub, during a stop at the edge of the freeway. But, from that vantage point, downtown Oakland is a world away.

He explained that decisions about where to put the freeways correspond to the old "redlining" maps. Redlining was a racist policy of denying home loans to African Americans (or anyone who lived in predominantly African-American communities). "Once the federal government started insuring home loans, the only places that were seen as good investments didn't have 'negros' living there," as the old loan guidelines and bank documents dictated, said Holub. Deprived of the ability to borrow money, purchase homes, and accumulate wealth, black neighborhoods suffered--they were further deprived of basic services, and quickly became blighted. Then infrastructure, such as freeways, was put through these blighted neighborhoods, forever cutting them off from the economic region as a whole. "The old redlines from the 1930s match the racial divides we see today," said Holub.

This, he explained, is why suspicion of "complete streets" advocacy exists. "Just putting RB [of Scraper bikes, in the lead image] on the Oakland Bike and Pedestrian board doesn't change the dynamics of the city."

So what would change the dynamics of the city? Holub said that some of it will require repairing the fabric of the city, with proposals such as filling in I-980 and turning it into a boulevard, to reconnect West Oakland with downtown. That would be a good start, but there remain infrastructure divides throughout Oakland. The 66th Avenue Gateway park, mentioned at the start of this story, was completed in 2008 with Measure DD funds. DD was a $198.25 million bond measure for waterfront improvements.

But because of the physical divisions that remain throughout Oakland, there are still a lot of bridges that need building before neglected communities will have access to such parks and the other benefits of living in a diverse, economically strong and dynamic city. In addition to the physical divisions that need bridging, there's the need to build trust between planners and the communities that have gotten so short-changed.

Moreover, Holub warns advocates to question complete streets plans--after all, the freeways and the elevated BART structure were originally sold as progress and as solutions to 'blight.' Instead, they reinforced redlining and segregation with concrete and rebar. "Be suspicious. Who is being left out of the plans this time?"