Editor's note: At a press conference on Thursday, Supervisor Alan Wong presented a map of crashes to make it appear as if the construction of Sunset Dunes park and the closure of a segment of the Great Highway had caused more car crashes. Jacob Zwart, a professional data scientist, broke down the real San Francisco crash data and published a statistical analysis of Wong's assertion on Github. Streetsblog republished it here with permission.

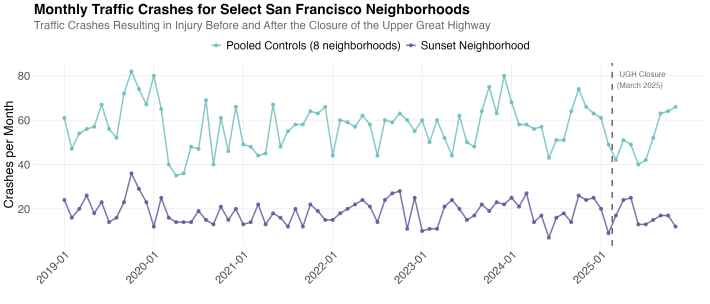

Did the Upper Great Highway closure make Sunset neighborhood streets less safe? Supervisor Alan Wong claimed it did at a January 8 press conference, citing a simple year-over-year map comparison of crash data. But my analysis, using the same DataSF crash data with rigorous statistical controls, finds no evidence to support that claim, and if anything, the data suggest the opposite.

Simple before-after comparisons like the one Supervisor Wong used are misleading because crash rates fluctuate year-to-year for reasons unrelated to any single road closure: weather patterns, economic conditions, return-to-office mandates, and major events all affect traffic citywide. To isolate the road closure’s actual effect, I applied a Before-After-Control-Impact (BACI) design; a statistical method commonly used in ecological research that compares changes in the affected area to changes in unaffected control neighborhoods.

If the closure caused more crashes, the Sunset should show a larger increase (or smaller decrease) than control areas. It doesn’t.

Study Design

The impact area includes Sunset/Parkside, Outer Sunset, Inner Sunset, and Golden Gate Park neighborhood crash data, or the neighborhoods most directly affected by traffic re-routing due to the closure. To serve as controls, I selected 8 San Francisco neighborhoods geographically separated from the closure that would not experience spillover traffic effects: Bernal Heights, Outer Mission, Excelsior, Oceanview/Merced/Ingleside, Portola, West of Twin Peaks, Bayview Hunters Point, and Pacific Heights.

The analysis compares crash rates during the same seasonal window (April through November) across all years to control for seasonal variation. The “before” period spans six years (2019–2024), providing 48 months of baseline data, while the “after” period covers 8 months of post-closure data from 2025.

To ensure robust findings, I applied two independent statistical methods: a negative binomial generalized linear model (GLM) testing whether the Incidence Rate Ratio (IRR) differs from 1.0, and Welch’s t-test on the difference-in-differences. If results from both methods agree, then it stengthens the conclusion.

BACI Analysis: Controlling for Citywide Trends

Results across all 8 control neighborhoods

| Control Neighborhood | Before | After | BACI | IRR | p(GLM) | p(t-test) | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bernal Heights | 6.1/mo | 6.8/mo | -2.65 | 0.81 | 0.257 | 0.300 | -0.47 |

| Portola | 3.4/mo | 3.8/mo | -2.29 | 0.82 | 0.388 | 0.291 | -0.39 |

| West of Twin Peaks | 5.5/mo | 5.4/mo | -1.83 | 0.92 | 0.680 | 0.317 | -0.40 |

| Oceanview/Merced/Ingleside | 3.9/mo | 3.8/mo | -1.81 | 0.93 | 0.764 | 0.369 | -0.35 |

| Pacific Heights | 4.2/mo | 4.0/mo | -1.79 | 0.93 | 0.766 | 0.405 | -0.34 |

| Excelsior | 6.0/mo | 5.2/mo | -1.25 | 1.02 | 0.935 | 0.569 | -0.22 |

| Outer Mission | 7.5/mo | 6.5/mo | -0.92 | 1.04 | 0.841 | 0.712 | -0.17 |

| Bayview Hunters Point | 20.5/mo | 18.0/mo | +0.56 | 1.02 | 0.878 | 0.830 | +0.09 |

| Pooled (all 8) | 57.1/mo | 53.4/mo | +1.73 | 0.96 | 0.739 | 0.690 | +0.20 |

| Impact (Sunset area) | 19.0/mo | 17.0/mo | — | — | — | — | — |

Key results

Crash rate changes in the Sunset neighborhoods are statistically indistinguishable from changes in control neighborhoods.

Neither the GLM nor Welch’s t-test found statistically significant effects in any of the 8 control comparisons (all p > 0.26), and both methods agree on this conclusion. The mean BACI effect of -1.50 crashes/month and mean IRR of 0.94 (-6.4% relative change) both suggest the Sunset area saw slightly fewer crashes than expected, but these differences fall well within normal variation. 7 of 8 control comparisons point toward fewer crashes in the impact area after the closure.

The pooled analysis combining all controls shows an IRR of 0.96 (p = 0.74) and a 95% confidence interval for the BACI effect spanning -7.85 to +11.31 crashes per month, clearly including zero. The mean Cohen’s d of -0.28 indicates a small effect size, meaning the observed difference is not only statistically insignificant but also practically negligible.

Understanding the statistics:

- BACI effect measures how much the impact area changed beyond what controls changed. The mean of -1.50 crashes/month means the Sunset averaged 1.5 fewer crashes than expected, but this isn’t statistically significant.

- IRR (Incidence Rate Ratio) of 0.94 means the Sunset had 6% fewer crashes than expected (94 per 100 expected). With p = 0.74, this could easily be chance.

- Cohen’s d of -0.28 is a small effect size (0.2 = small, 0.5 = medium, 0.8 = large). This tells us the difference isn’t just statistically insignificant, it’s also practically small.

All three measures from these statistical tests point the same direction -> no detectable effect on traffic crashes resulting in injury due to the closure of the Upper Great Highway to automobiles.

Personal Anectdote

I live in the Outer Sunset in the Taraval and 40’s area, and I walk on average 4-6 miles per day to drop my kid off at daycare, go to the grocery store, head to the beach, or just to enjoy the SF weather. Personally, I have not noticed a change in my safety while walking around the Sunset streets before or after the closure of the Upper Great Highway, except for one location - Sunset Dunes Park. This park is the only place I feel completely safe as a pedestrian and it is a true gem that I hope to enjoy with my family, friends, and neighbors for many years to come.

Jacob Zwart is an environmental and data scientist