Protected bike lanes, protected intersections, contraflow bike lanes--think of some top-notch, quick-build bicycle infrastructure, and San Jose's got it.

In the past year, the city has laid down ten miles of quick-build protected bike lanes. Some are parking protected. Some are protected by rows of robust-looking K71 plastic bollards. San Jose's quick-build scheme costs the city only $1.5 million for an impressive transformation of the downtown core. Vignesh Swaminathan, a consultant who helped design the city's quick-build network, explained that they saved money by making the installations a part of planned repaving.

Unlike in San Francisco and other Bay Area cities, the new protected bike lanes are nearly all joined by protected intersections.

"Motorists and cyclists still get startled by them," explained Peter Bennett, who is in charge of the Bike and Pedestrian Program for San Jose. But he said they're learning how to navigate the new set-up--and it's working to reduce collisions. "Some people perceive it as inviting a right hook, but it's about a negotiation."

The idea is to force cars to slow down and make a tight turn--and to shift the relative angles of motorists and cyclists so they can make eye contact. "The treatment tries to induce a yield--and fifty percent of the time it's the cyclist that needs to slow," explained Bennett. Because of the treatments, both the motorists and cyclists have ample time to react to potential conflicts. In addition, the stop line for bikes is always placed far in front of the stop line for automobiles, to make cyclists more visible to drivers and to give them a head start across intersections.

Streetsblog recently covered the protected intersection pilot treatments in Berkeley, San Francisco, and Oakland. The San Jose design has the most in common with Oakland, since both use K71 plastic bollards and paint as an inexpensive, interim treatment. But San Jose has an added feature: Bennett and Swaminathan stressed that it's essential to have two marked radii, or guidelines, for drivers making the turn.

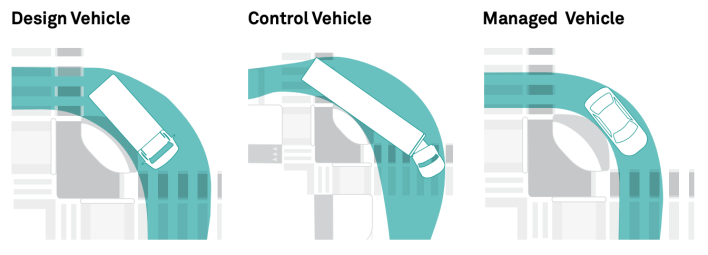

Some of San Francisco's treatments have an outer radius on turns, but they're only marked by paint. Oakland's protected intersections at Lake Merritt have only one radius. In San Jose, the outer radius includes the equivalent of Botts' dots--raised pavement markings that make noise if a car or truck tire drives over them. This warns the motorist that they're taking the turn too tightly and/or need to slow down. "If a truck is turning too tight, the driver feels the bumps," explained Bennett. In addition, the geometries are set up so the apron of the truck or bus can pass over the bumps without the vehicle taking out the plastic vertical bollards that mark the inner radius (see diagrams above).

And those bollards are set back far enough to keep cyclist or pedestrians from ending up in the truck's blind spot. They've also measured to make turns "as uncomfortable for truck drivers as possible." Bennett and Swaminathan explained that they did this by emulating minimum clearances at construction sites. "Truck drivers are trained to navigate them," said Swaminathan (who also gave Streetsblog a full tour of the infrastructure).

All of this may explain why Oakland's protected intersections, which lack that additional, dotted radius, had squashed bollards shortly after it opened, while San Jose's seem to be holding up better.

San Jose also made sure that bus stops were built with raised bike lane cut-throughs, as seen below:

The city used the same kind of quick-build bus stop islands that Oakland used on Telegraph. But Swaminathan said they upped the game by adding bollards to make sure cyclists didn't ride into the drainage channel against the curb. They also added safety railings and leveled the island with two-by-fours and some asphalt underneath, to greatly reduce the risk of someone in a wheel chair rolling off the platform and into the bike lane--or of a blind person mistakenly navigating into the path of a bike.

The city seems to have thought of everything, including providing new loading zones and even adding these armadillos to keep garbage dumpsters out of the bike lanes:

The plan is to slowly replace all of these plastic treatments with concrete.

While these installations went in amazingly fast, this didn't all happen overnight and there were some compromises. Swaminathan said he anticipated issues with the fire department, so he approached them before anything was built and assured them that building sufficient clearances for their trucks was "the single biggest priority." The result: the fire department was on board. The other result: San Jose ended up with more traditional bike boxes and faster turns than they would have liked in a few places, because the fire department insisted everything be built to accommodate their oldest fire truck (despite the fact that it will soon be scrapped). The city also had to compromise with the local transit agency, VTA, which was concerned about clearances for buses (note the slightly less-than-ideal turning radius in the intersection six images up).

San Jose has moved forward with an impressively integrated, protected system that should work for all users. Most importantly, they have focused on keeping intersections safe. The Dutch, Danish, and others have long been moving away from so-called "mixing zones," which San Francisco, Oakland, and other Bay Area cities continue to install (that's a standard installation where bicycles going straight are somehow supposed to zipper in with right-turning cars and trucks). Mixing zones are the best way to maximize vehicular throughput, but San Jose has decided that safety for people on foot, bike, and scooter is more important.

The good news is that what San Jose has accomplished didn't cost much money. It was all about political will--it helps to have the backing of a "bicycle mayor" such as Sam Liccardo--and a few important details that other cities can emulate.

A few more pictures of San Jose's treatments below: